Biographies

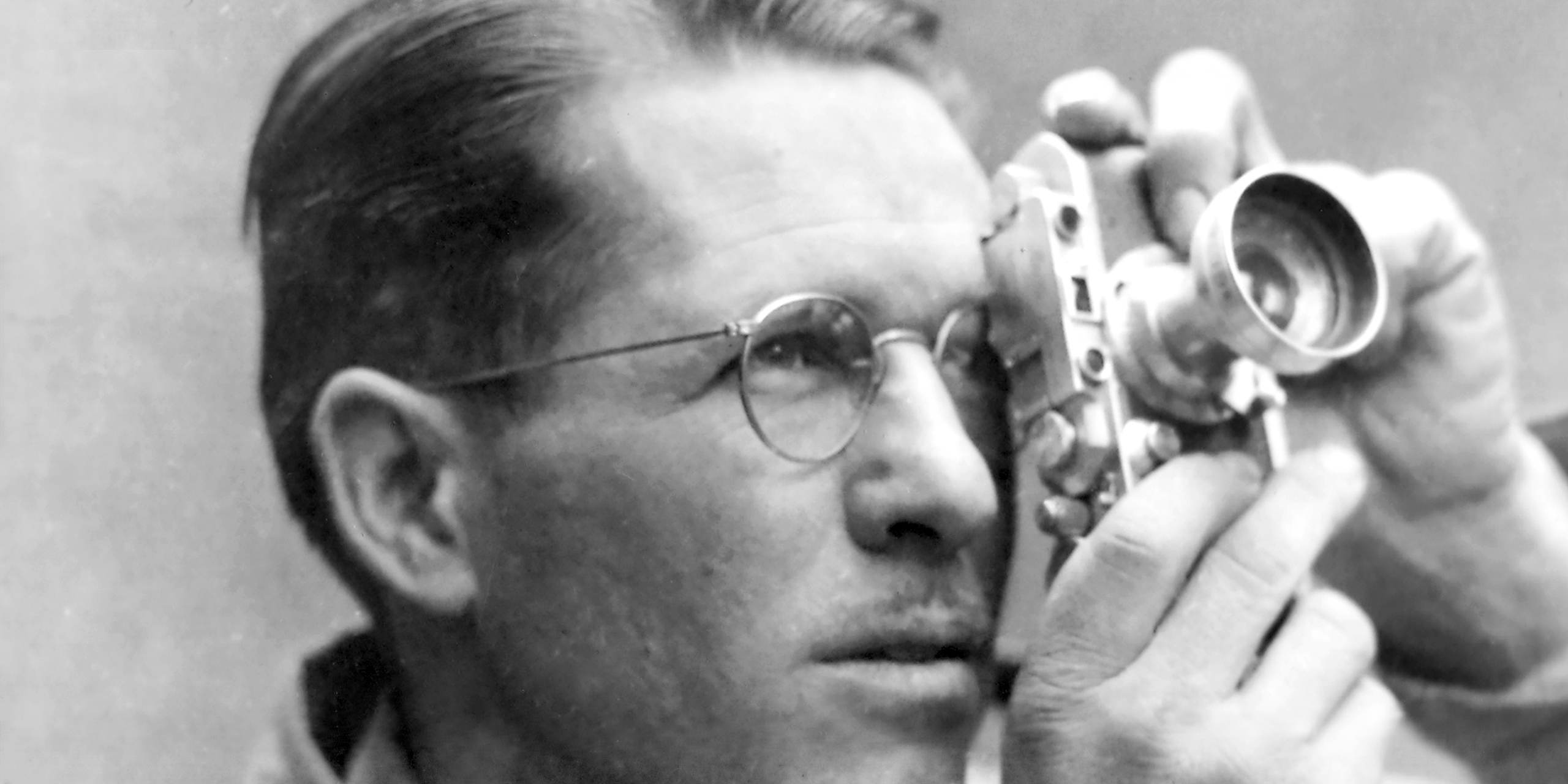

Gérard Raphaël Algoet

Belgian military photographer

23 September 1902 in Heestert, West Flanders

9 May 1989 in Oppem, Brabant

Before World War II and during the first years of the hostilities, Gérard Raphaël Algoet worked as the photographer of a Catholic mission in India for more than ten years. He returned to Europe in 1943, having been recruited by the Belgian embassy in Great Britain for service in the Brigade Piron, which was established for the purpose of liberating Belgium. Along with his compatriot, the journalist Paul Lévy, he accompanied this unit as a photographer and witnessed the liberation of Brussels.

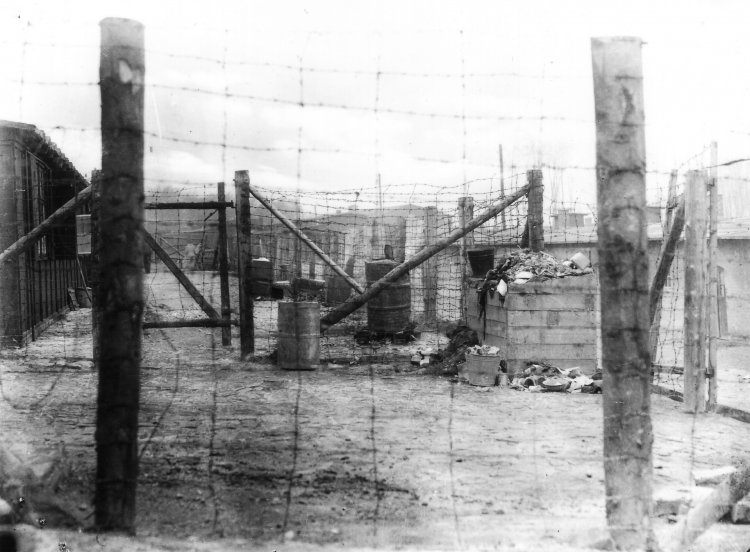

After that event, the two followed the U.S. American troops through Germany as correspondents for the Belgian government. Lévy and Algoet were the first Western journalists to enter Berlin after its destruction. They reached the Buchenwald concentration camp shortly after its liberation, sometime before 16 April 1945, and spent several days there. Gérard Raphaël Algoet focussed primarily on documenting the conditions in the Little Camp and the Belgian inmates. His further stops included the Buchenwald subcamps Ohrdruf and Weferlingen as well as the Mittelbau concentration camp near Nordhausen and the Dachau concentration camp. Algoet and Lévy reported from the Reich capital Berlin at a time when it was still occupied by Soviet troops.

After 1945 Gérard Raphaël Algoet taught at the Higher Belgian Film Institute in Brussels. He died in Oppem, Brabant in 1989.

Photographer unknown, April 1945

Private collection

Georges Angéli

French political inmate

12 January 1920 in Bordeaux

14 September 2010 in Chatellerault

Georges Angéli began his three-year training as a professional photographer at the age of 14. In July 1939 he volunteered for military service and was put to work in a unit of the French army’s photo service. A year later he and his unit were sent to Algeria. He returned to France in the summer of 1942 and a few months later was conscripted by the Germans to work at a submarine base on the Atlantic. Georges Angéli decided to join a resistance group abroad. He was arrested by the Gestapo while crossing the Franco-Spanish border and committed to Compiègne.

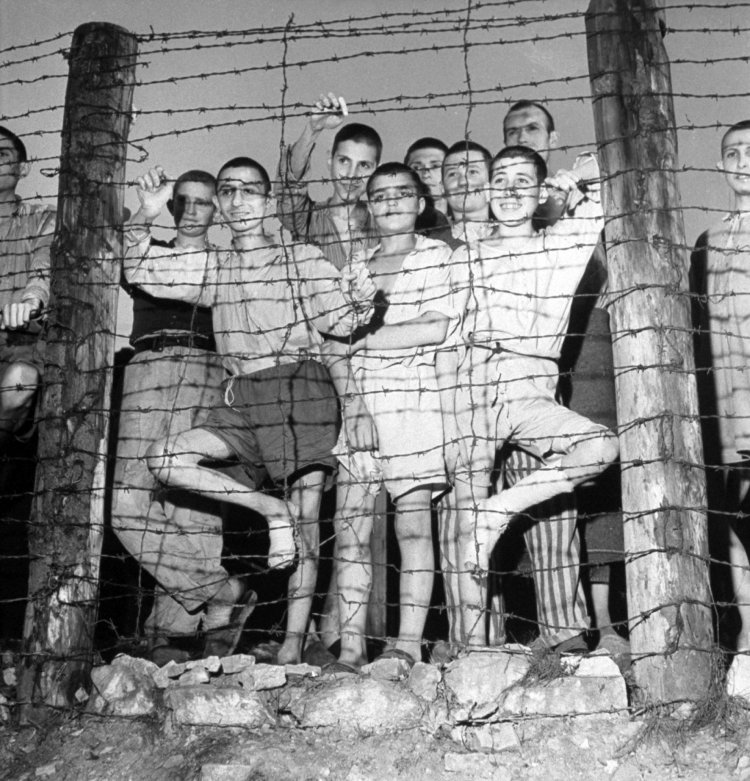

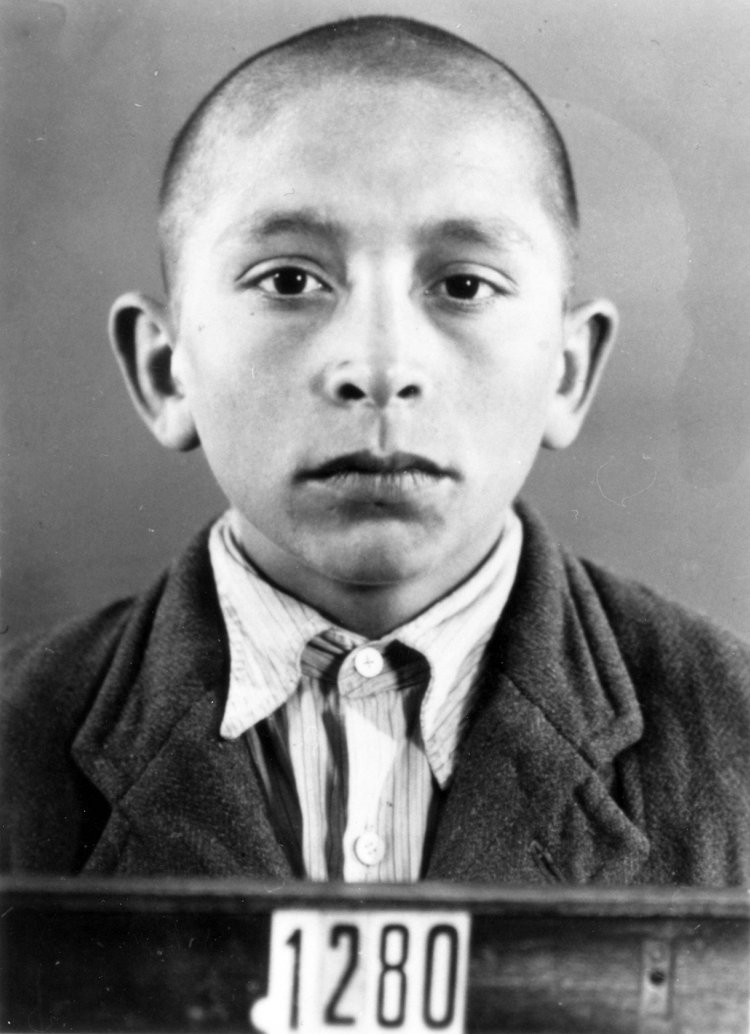

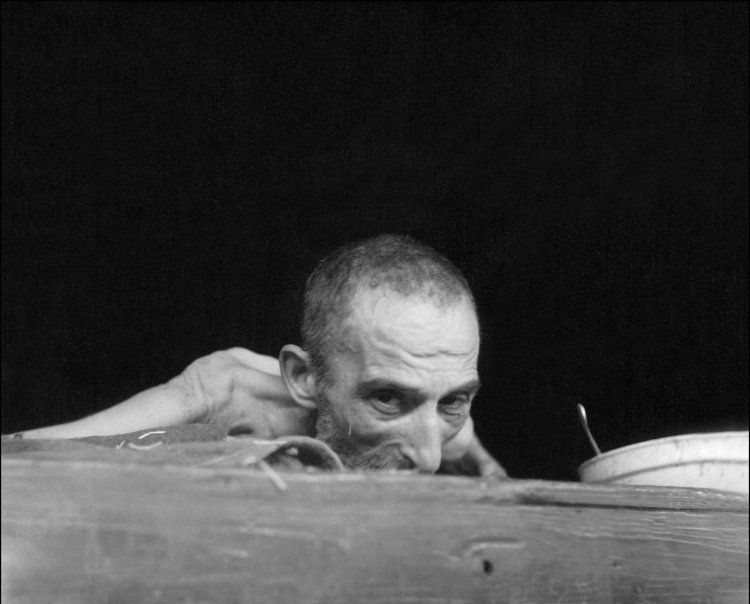

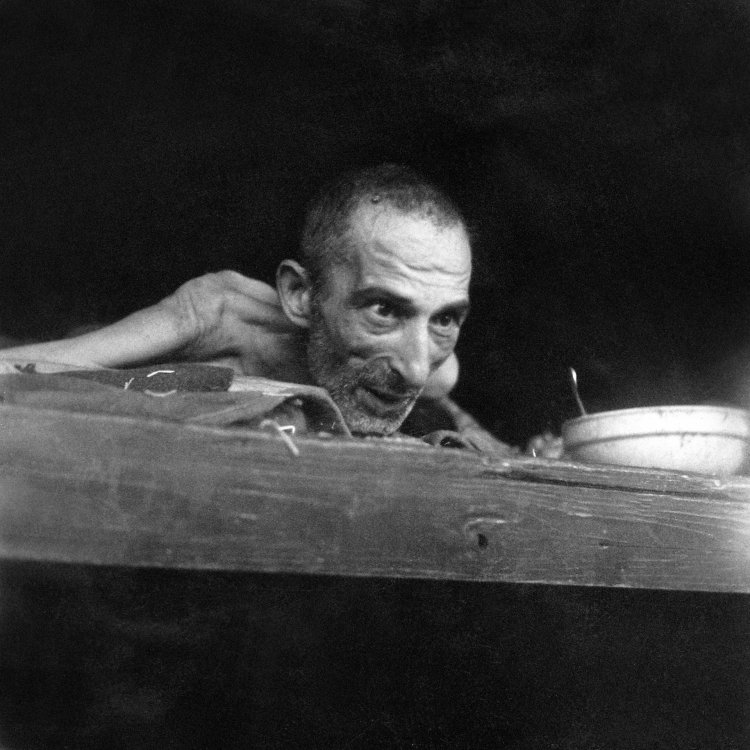

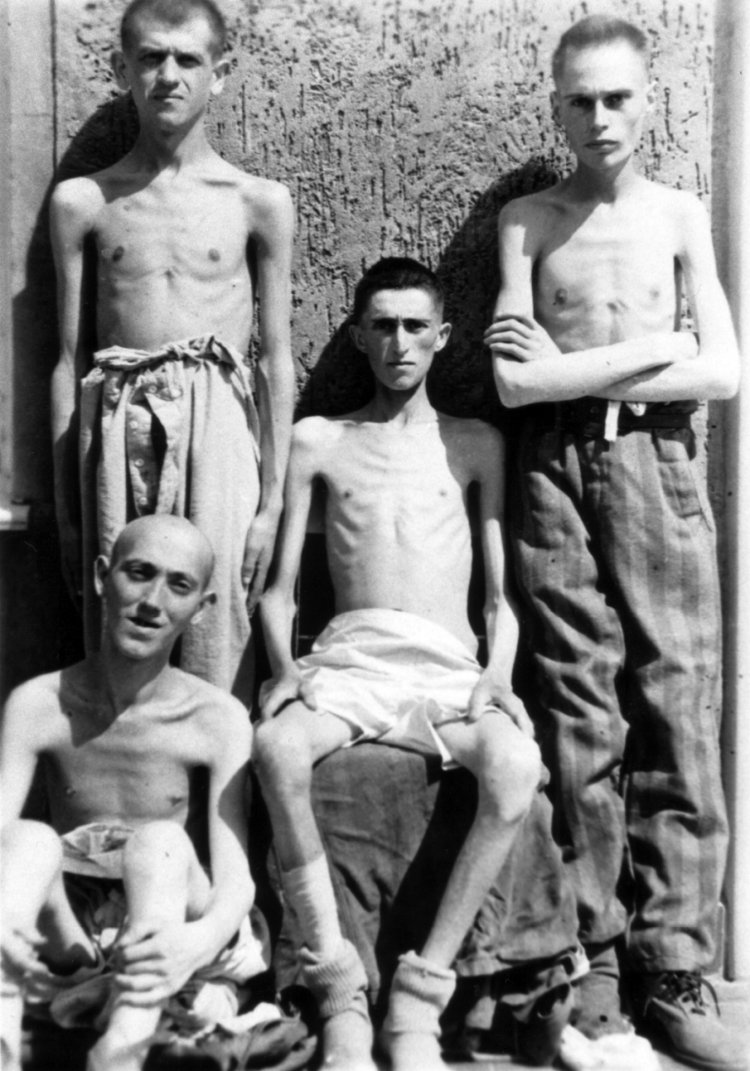

A few weeks later, Angéli was transferred to the Buchenwald concentration camp. There he was registered as a political inmate and assigned the number 14824. On account of his professional experience he was assigned to work in the records office. In June 1944 – on a Sunday, when there were no SS in the camp – Georges Angéli stole one of the photo department cameras and secretly took eleven photos, most of them in the “Little Camp”. His reason for carrying out this daring act was to produce testimony that would outlast the camp. Angéli hid the original rolls of film in a bundle with other photos somewhere outside the photo department; as a result, they survived the air attack of August 1944 intact.

Following the liberation, Georges Angéli returned to France. His photos were shown in small, improvised exhibitions organized by the Fédération Nationale des Déportés et Internés, Résistants et Patriotes (F.N.D.I.R.P.). The characteristic nature of the photographs as well as their significance and the history of their origination and use did not become known to a wider public until the 1990s. Angéli worked as a photographer until his early retirement and lived in a home for the elderly in Chatelleraut from 1998 until his death in 2010.

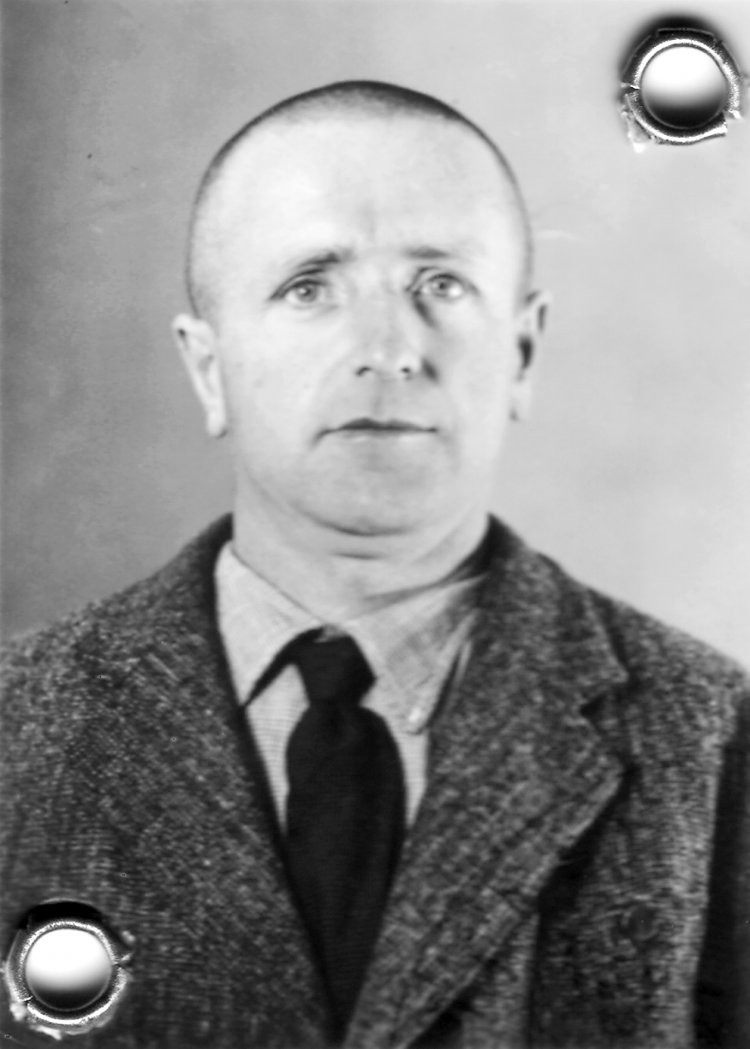

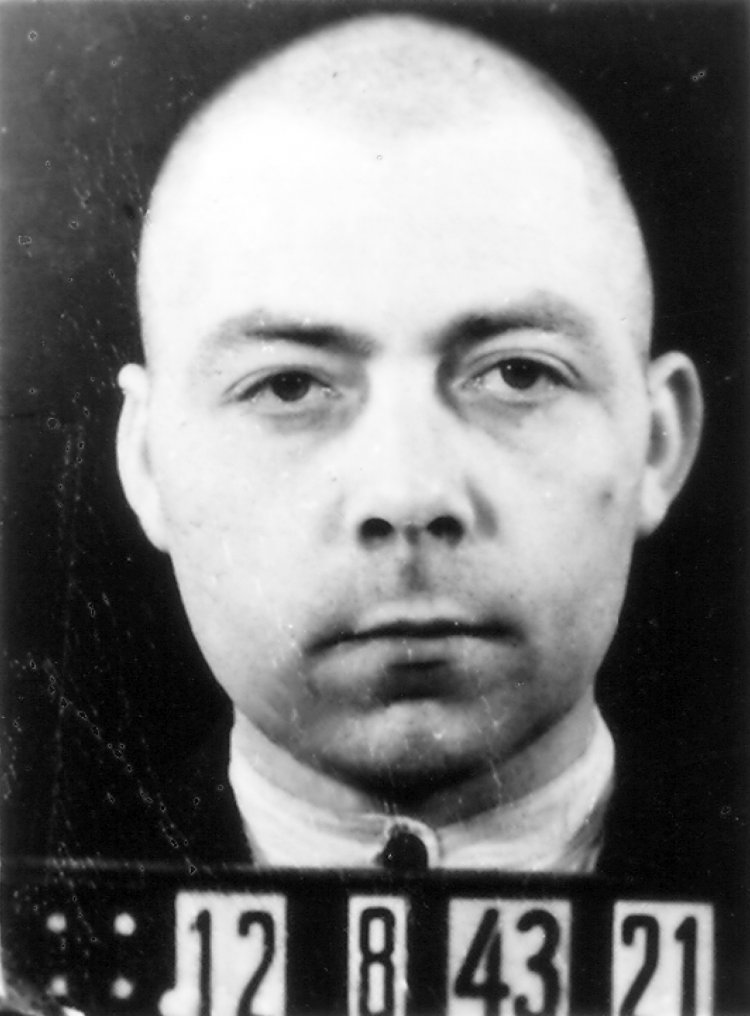

Hubert Peitz, SS Oberscharführer, 25 February 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

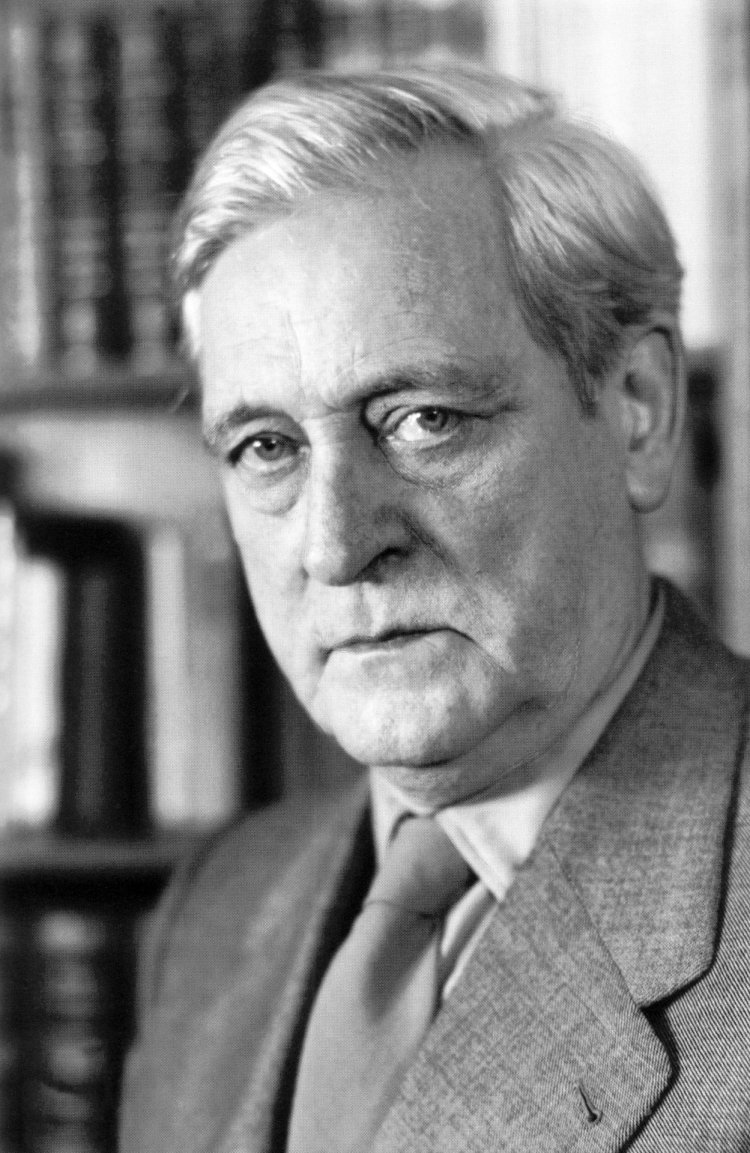

Günther Beyer

German professional photographer

1 January 1888 in Grossbrembach near Weimar

7 October 1965 in Weimar

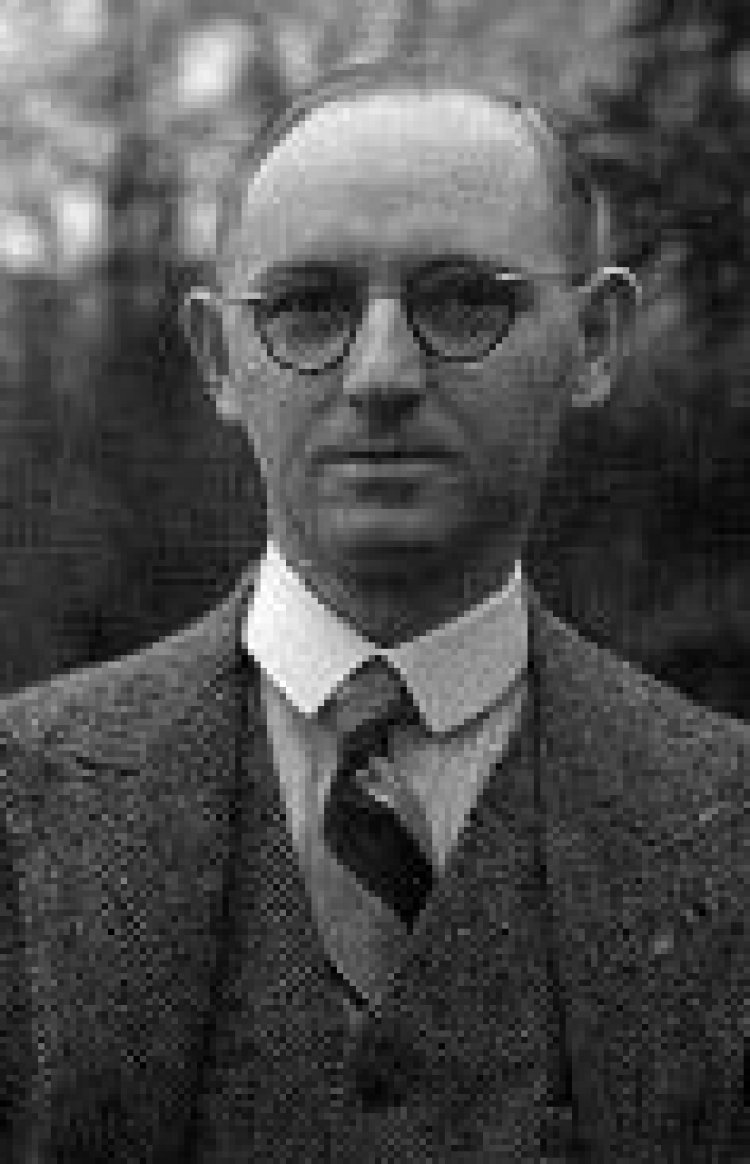

In 1910, having completed training at the college of education in Weimar, Günther Beyer began working as a teacher in Stützerbach. Starting in 1914, he served as a soldier in World War I. In 1919, he moved to Possendorf outside Weimar, and a year later to the city of Weimar itself. He began studying art history at the University of Jena the same year, and completed those studies in 1924. In Weimar he opened “Beyers Wissenschaftliches Institut für Projektionsfotografie”. In 1932 Günther Beyer resumed his work as a teacher, now in Arnstadt. In addition to his teaching activities, he headed the school film library there.

In 1934 Beyer was appointed director of the State of Thuringia’s rental centre for educational films, which was located in Weimar. With interruptions due to military service, he occupied that position until the end of the war.

The heaviest Allied air attack on Weimar took place on 9 February 1945. In the days and weeks that followed, Günther Beyer roamed the streets of Weimar with his camera. He took more than two hundred photos documenting the city’s destruction.

From 1946 onwards, Beyer again worked as a freelance photographer. He founded the “Bildverlag Günther Beyer, Weimar” and, working with his son Klaus G. Beyer, published numerous photo books over the years, two of them portraying the city of Weimar. Günther Beyer died in Weimar in 1965.

Klaus G. Beyer, ca. 1957

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Margaret Bourke-White

U.S. war correspondent

14 June 1904 in Bronx, New York

27 August 1971 in Stamford, Connecticut

Margaret Bourke-White already began taking pictures as a teenager in New Jersey. In 1929 she became the first photographer on the staff of Fortune, a magazine dedicated to propagating industrial progress. In 1936 she developed a new genre – the photo report – for Life magazine, an achievement that made her world-famous.

With the author Erskine Caldwell – her husband from 1939 to 1942 – she published “You Have Seen Their Faces”, a sensational photo report about the deplorable state of social affairs in the American South. After that, there was hardly a country or person of distinction she did not portray. For Life she went to Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Egypt, China, and the USSR; she portrayed Stalin and was in Moscow during the German offensive in the winter of 1941.

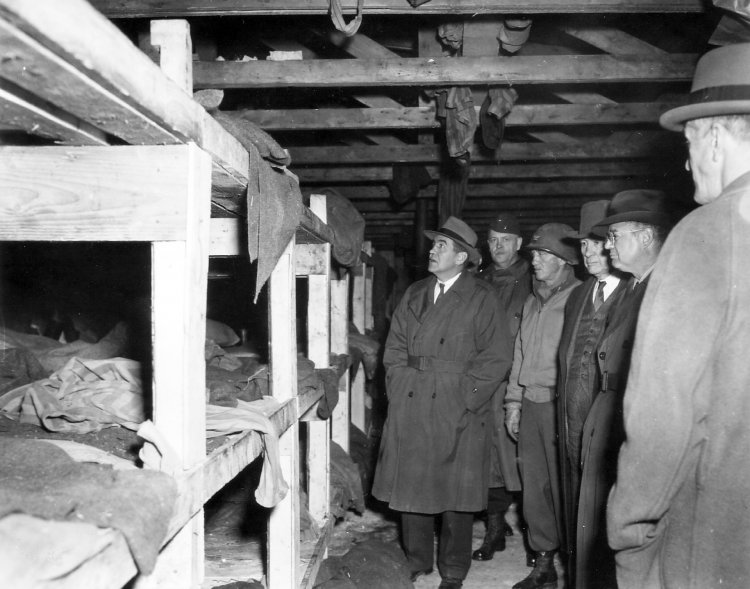

In 1942 she was the first woman to be accredited by the U.S. Army Air Corps. She documented the air war in England and the theatres of war in North Africa and Italy, then going on to accompany the Third U.S. Army under General Patton in March 1945. On 16 April 1945 she was in Buchenwald during the Weimar citizens’ forced tour of the camp. One year later she published the book “Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly” about her impressions of April 1945.

After World War II she concentrated increasingly on social aspects in her reports. She went to India and portrayed Gandhi, and in the Korean War it was Bourke-White who documented the circumstances of the civilian population. At the same time, she was summoned before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and accused of supporting Communism.

In 1956, Margaret Bourke-White was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. In the knowledge of her condition, she published her autobiography Portrait of My Life in 1963. She died on 27 August 1971 following a fall in her house in Connecticut.

Carl Mydans, January 1938

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images, Munich

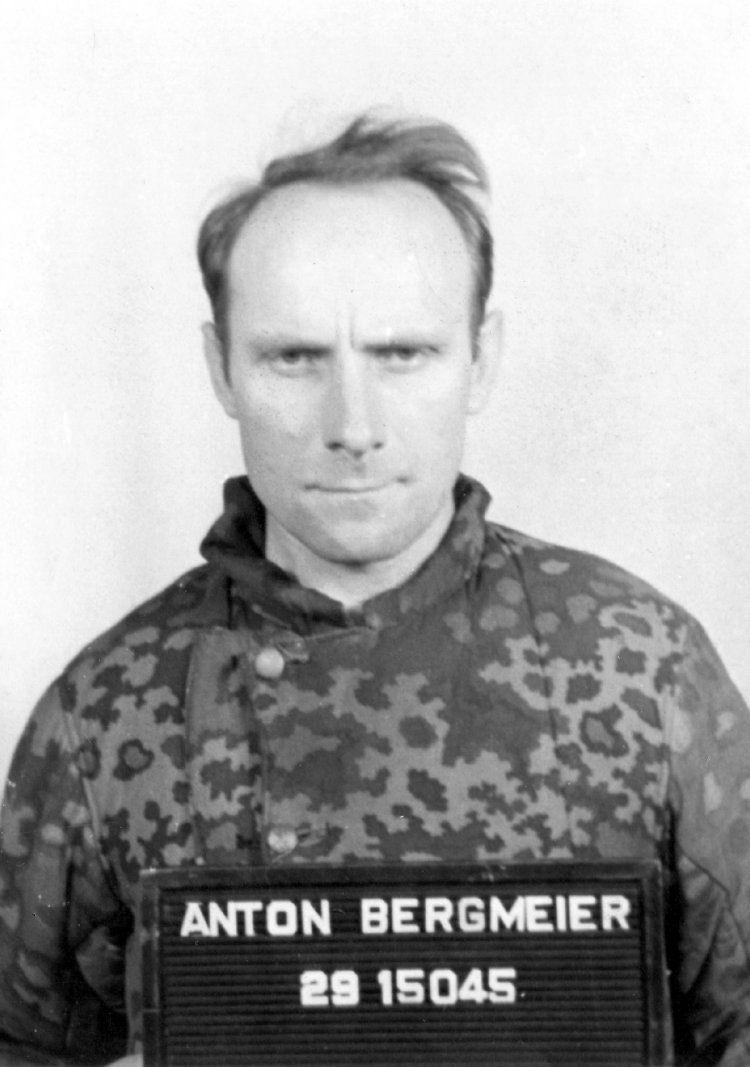

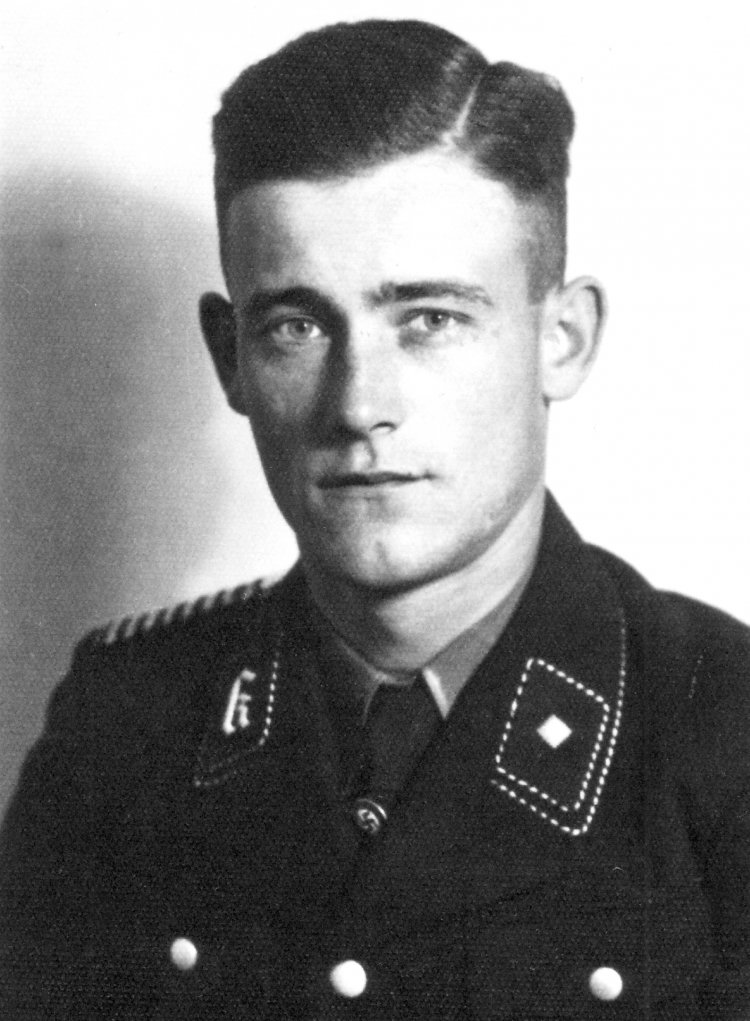

Georg Brendle

SS man

25 December 1921 in Probstried, Allgaeu

12 March 2008 in Volkmarsen

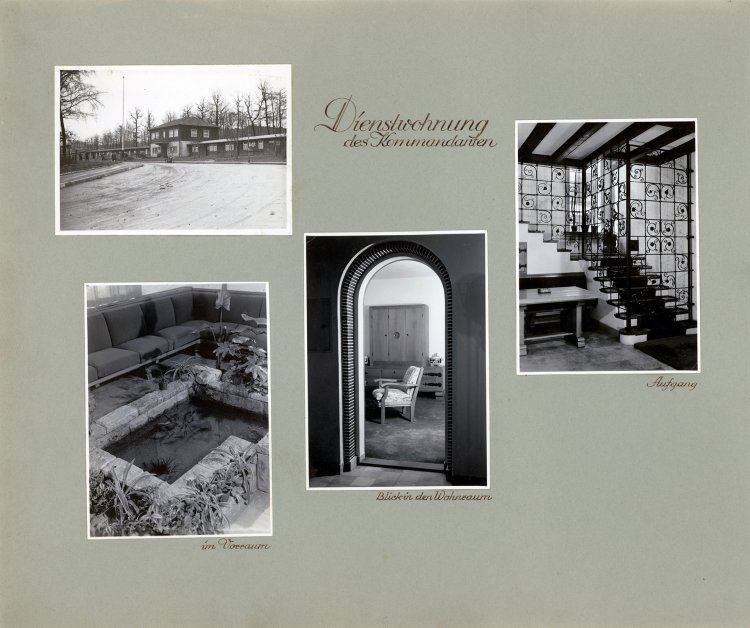

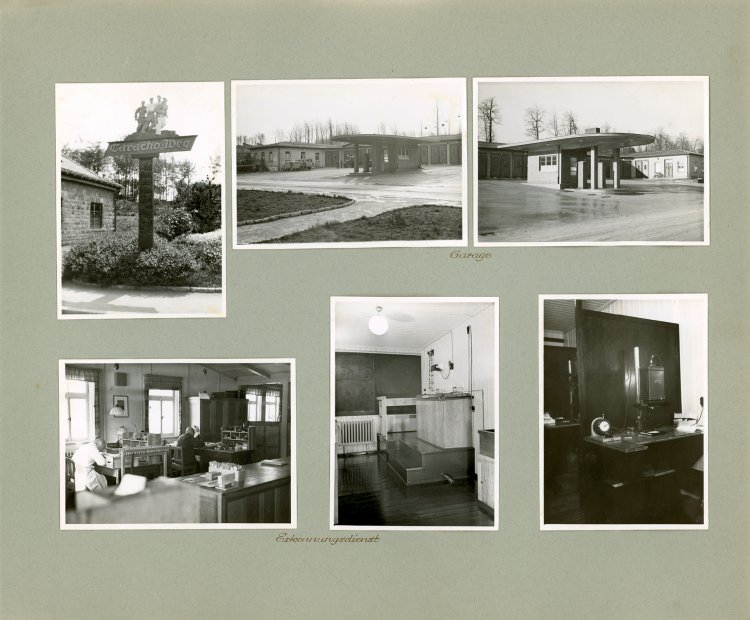

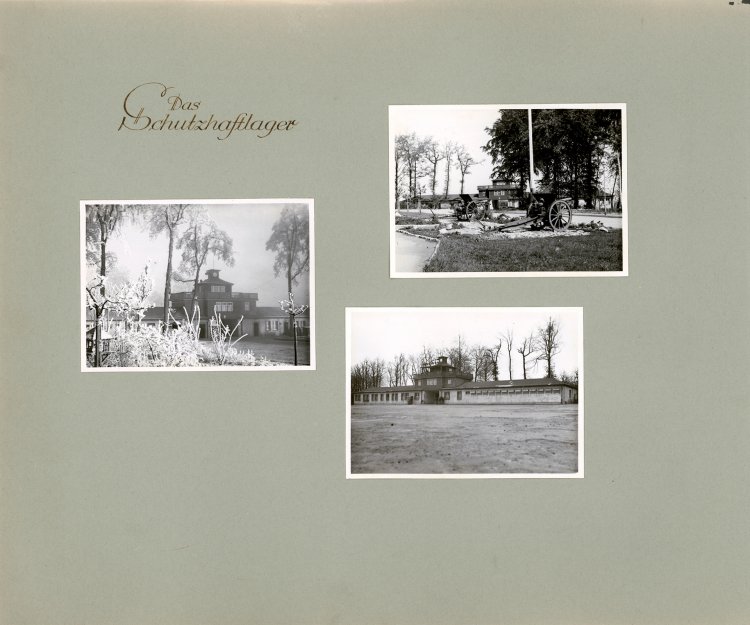

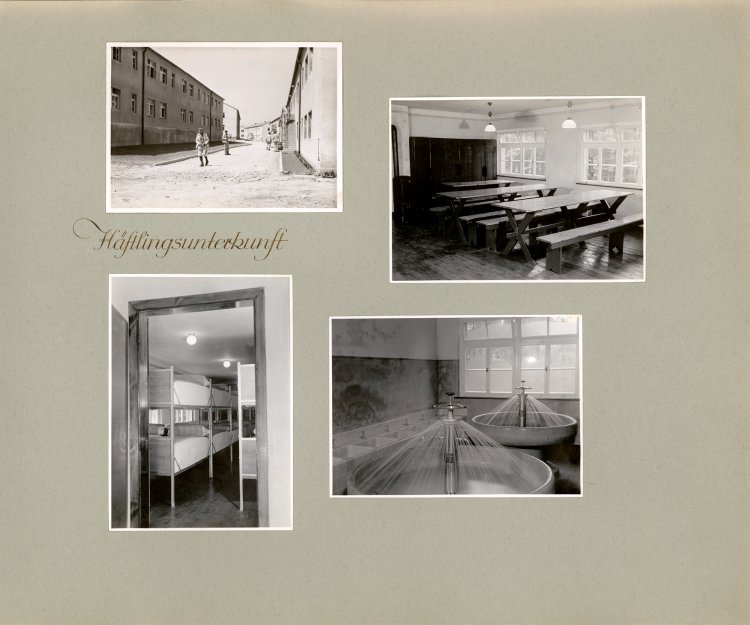

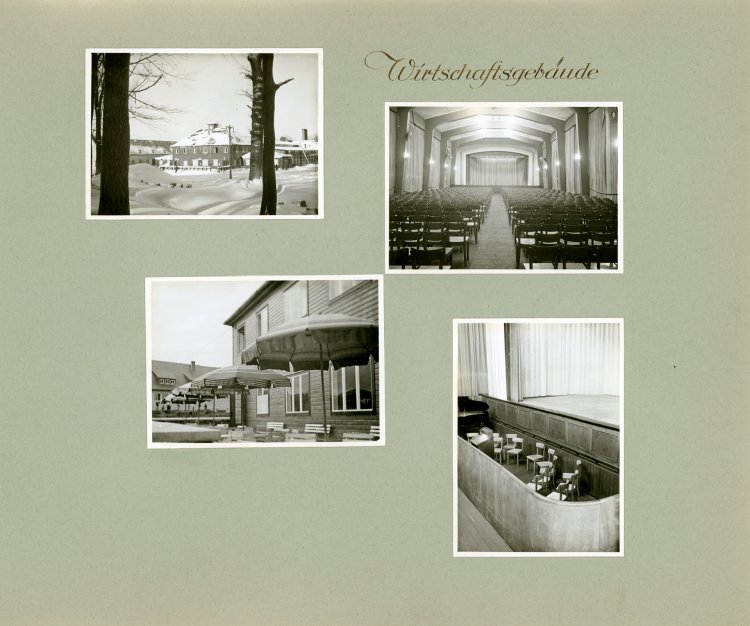

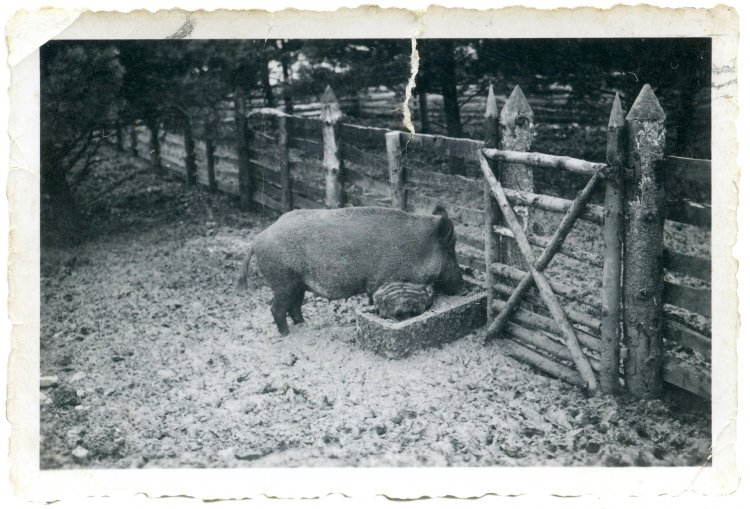

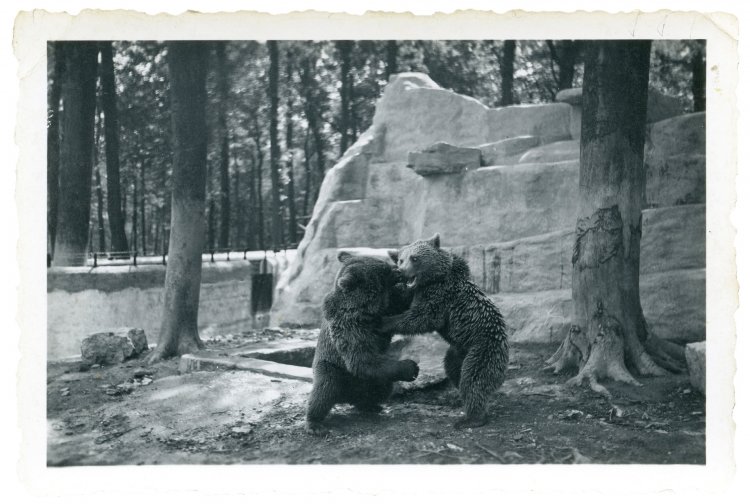

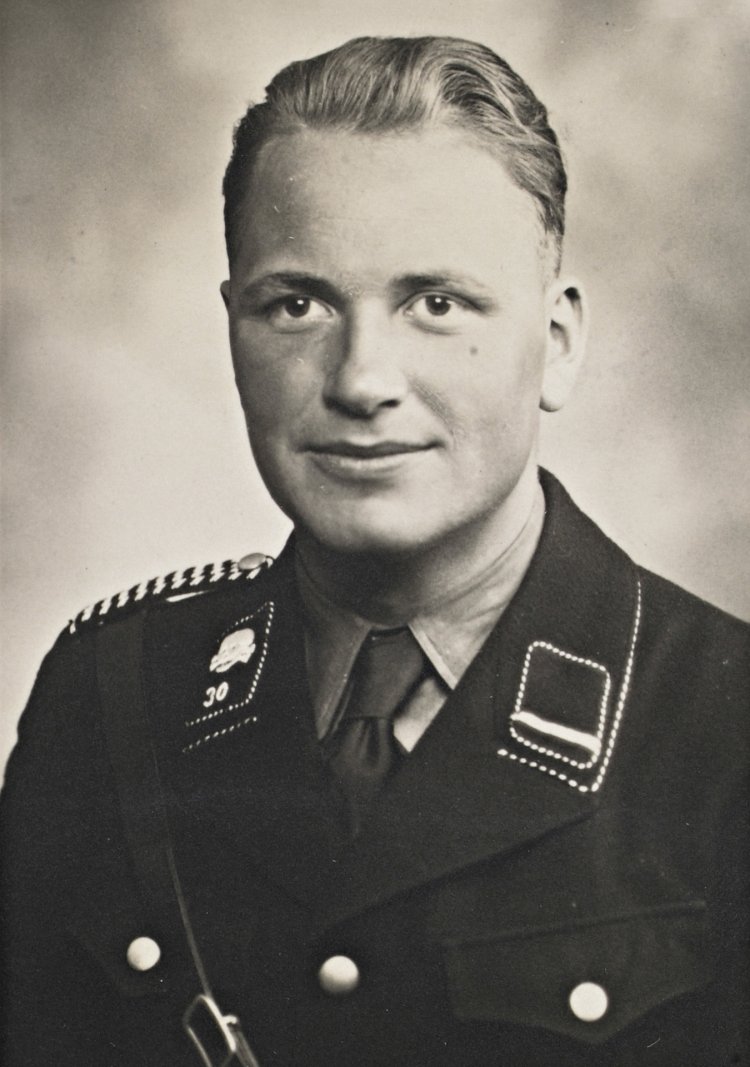

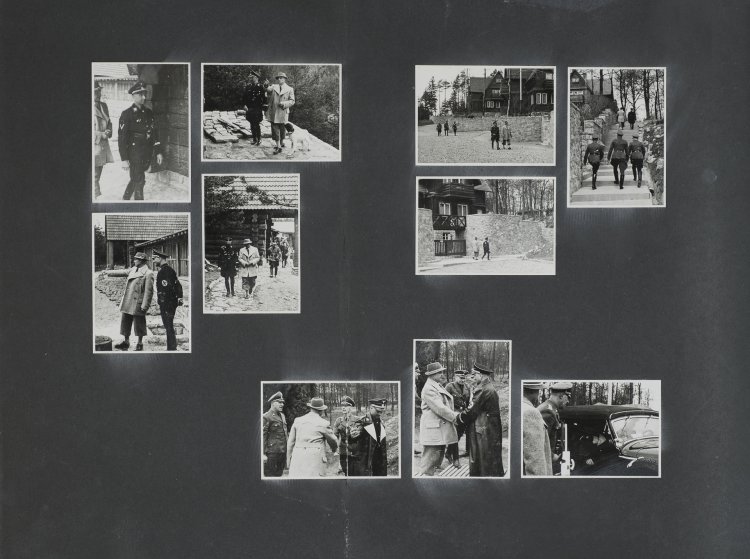

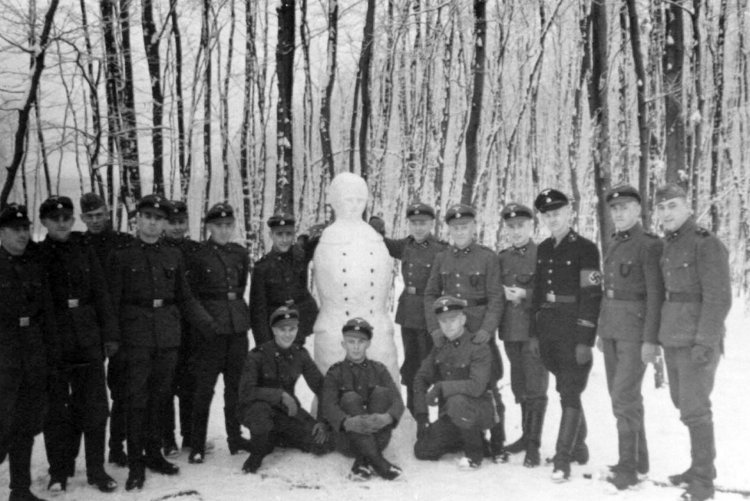

Georg Brendle was born an illegitimate child. Following six years of elementary school he was compelled to go to work as a farmhand. Beginning in 1936 he trained as a baker. On 5 October 1939, a few weeks after the outbreak of World War II, he enlisted with the SS.

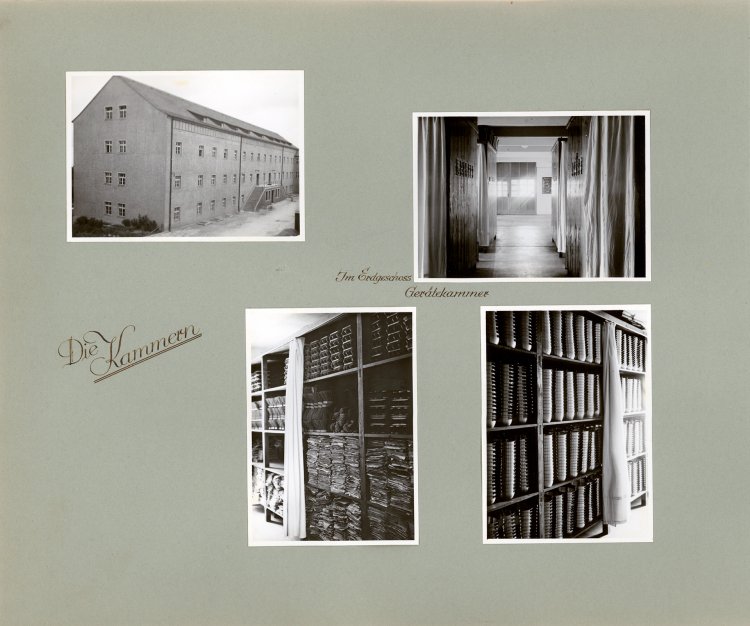

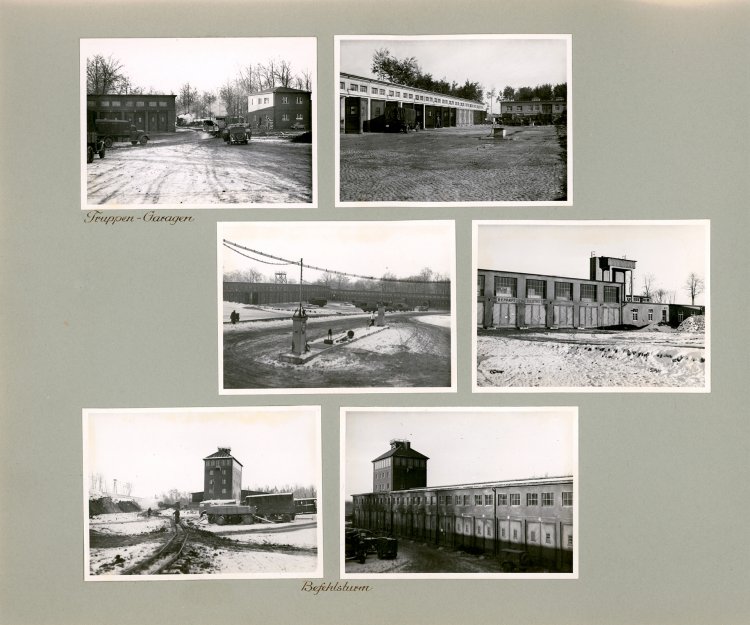

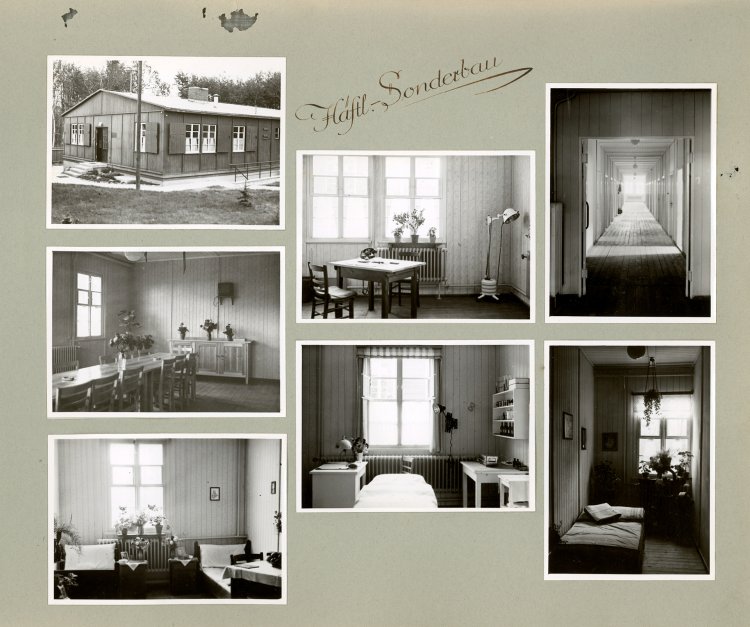

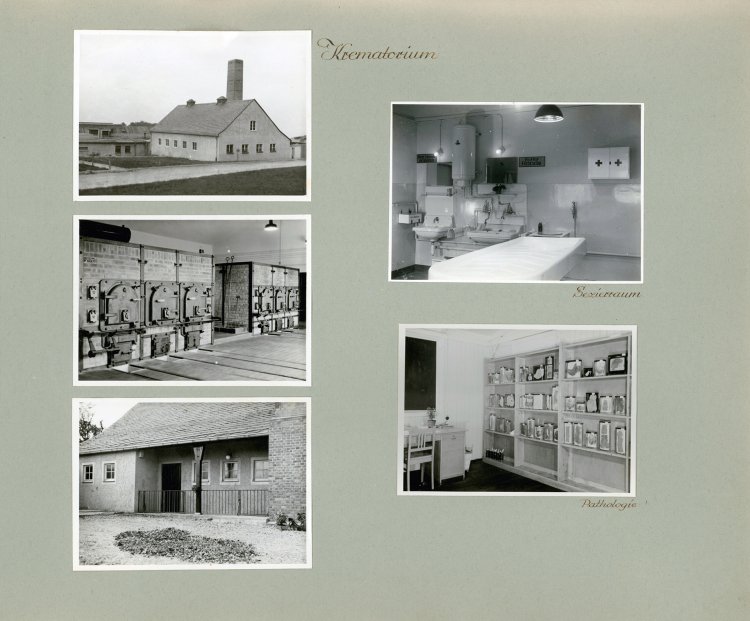

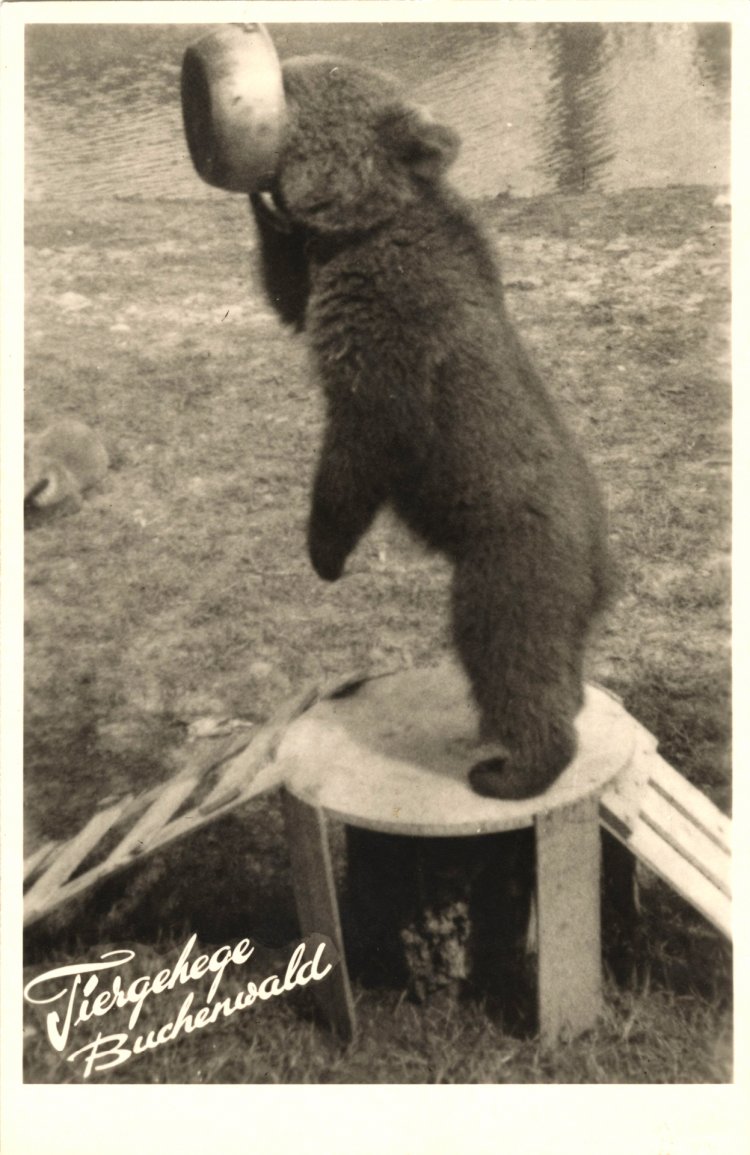

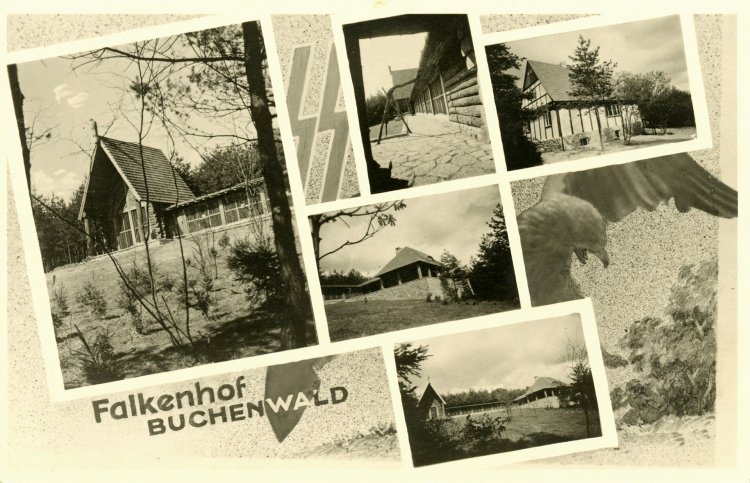

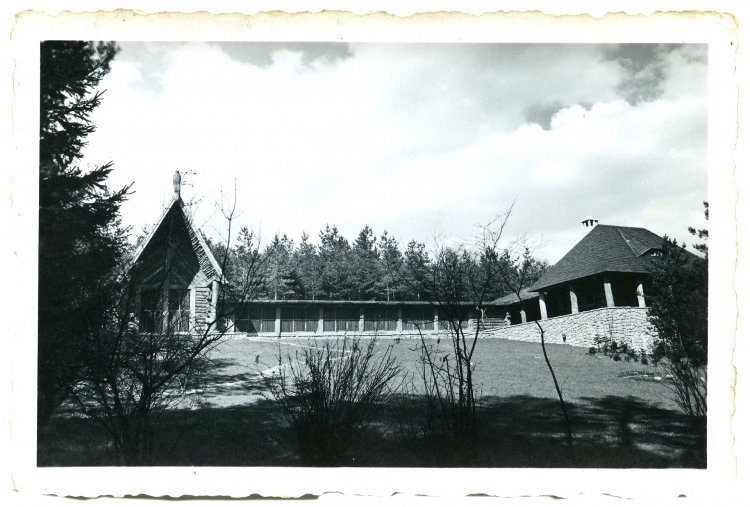

Before the month was over, he had been conscripted to recruit training at the SS bases in Weimar-Buchenwald and Dachau. Throughout his military training, he took pictures to remember his time both on and off duty, and pasted them into a private photo album which is decorated with SS runes and the inscription “Erinnerungen an meine Dienstzeit” (Memories of My Years in Service). He became a member of the newly formed SS Totenkopf Regiment 14 and spent the year 1940 at the Buchenwald base. On 10 December, Brendle was transferred to Holland, where his unit was assigned tasks related to coastal protection. Over the course of the war he was stationed in Pomerania, Poland, Lithuania, and Russia. In his album he commented on his transfer to Poland in May 1941 as follows: “Von dem herrlichen Deutschland, hinüber nach dem grässlichen Polen” (from wonderful Germany over to abominable Poland). On 2 July 1942 he was severely injured in the Wolchow Battle in Russia and it took him several months to recover. From late 1942 onwards, he served as a recruit trainer at the SS casern in Bad Arolsen. There, at a dance gathering, he met the woman who would later become his wife. In April 1944 he was awarded the rank of SS Oberscharführer. In May he married Helene L., who gave birth to their first child a few months later.

Following his attempt to flee Poland and the advancing Red Army by way of Czechoslovakia, he was taken prisoner of war by the Americans in May 1945, not to be released until January 1947. Afterwards he initially found employment in a sawmill and later, beginning in 1960, as a technical assistant with the Bundeswehr. He lived in Volkmarsen, Hessen until his death on 12 March 2008.

Photographer unknown, ca. 1941

Private collection

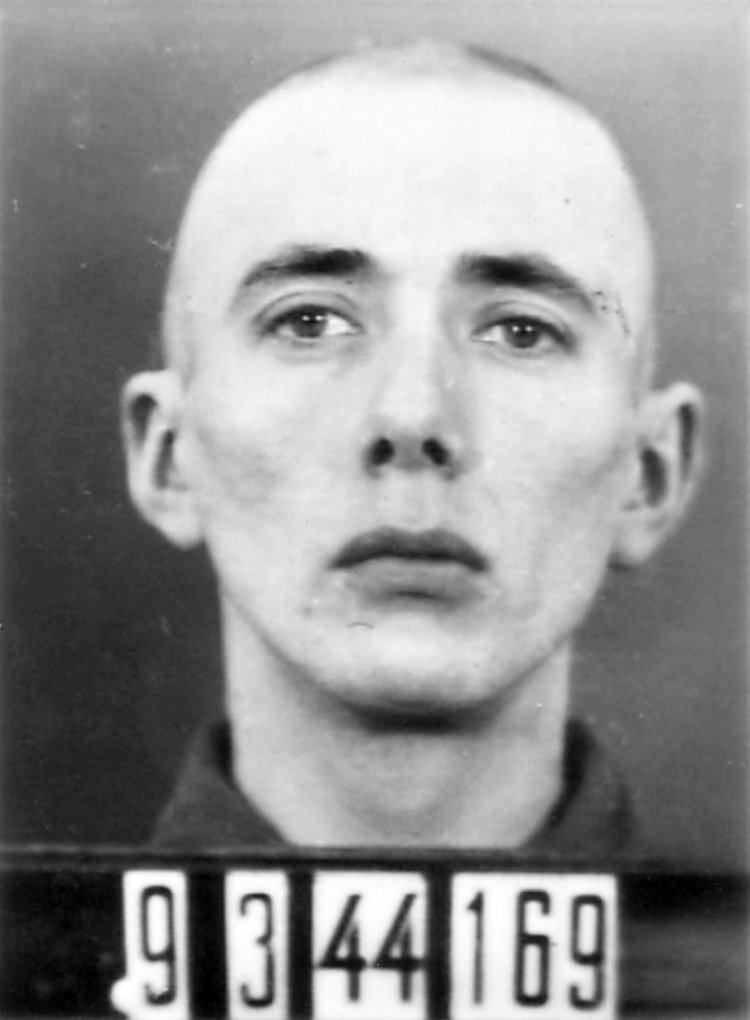

Walter Chichersky

U.S. Army photographer

6 December 1924 in Centralia, Pennsylvania

14 April 2008 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

Born of Ukrainian immigrants and nicknamed “Chick”, Walter Chichersky grew up in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. With his sisters Julia and Marie he performed with a Ukrainian dance group at the New York World’s Fair in 1938. He and four friends founded the band “Five Jars of Jam”, in which he played the accordion and the harmonica.

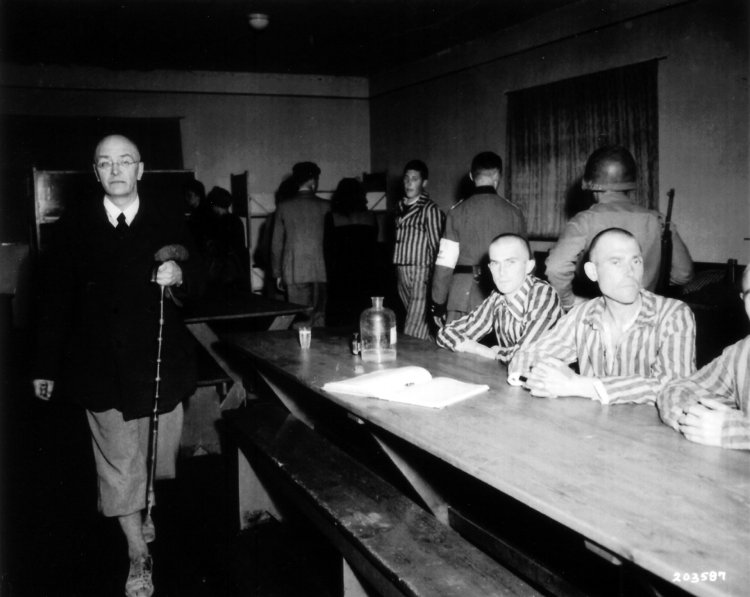

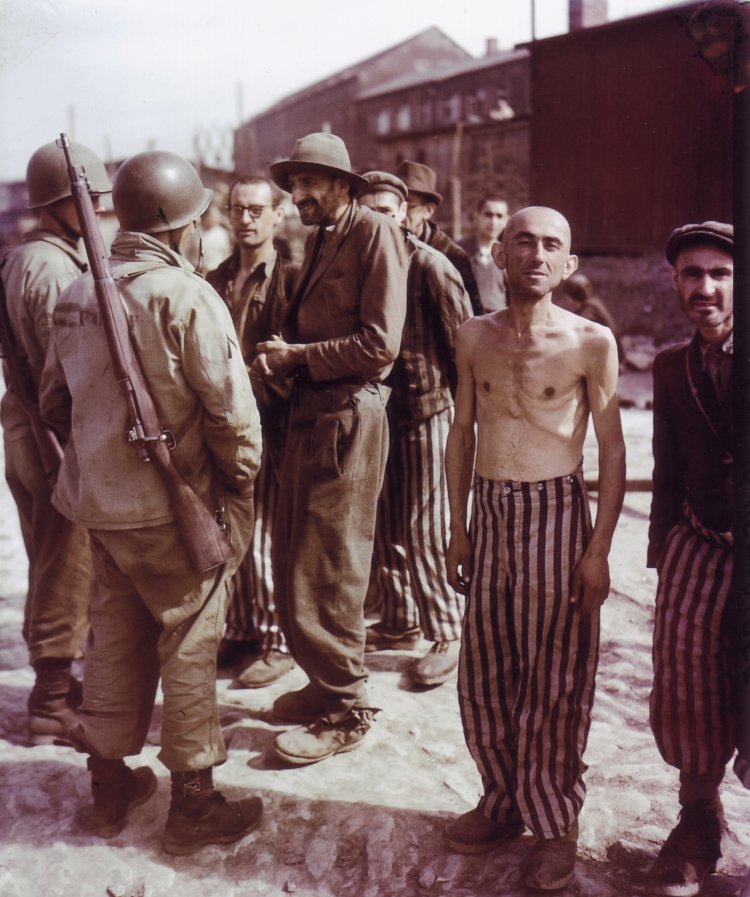

In December 1941, after the U.S. entered the war, he was drafted into the army; he was 17. From 1943 onwards, he accompanied General Patton’s Third Army in France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany as a Private First Class in the 166th Signal Photographic Company. He photographed the heavy combat with the First German Army during the liberation of the French city of Metz in November 1944, and the fighting that preceded the crossing of the Saar River on 19 December. When he arrived in Buchenwald on 14 April 1945, he was one of the first photographers to document the liberated camp. The shots he took on 16 April while the people of Weimar were being led through the camp are particularly striking. He was personally moved by the question as to how the Germans could have known about the events and permitted them to happen. On one photo he noted: “The German woman in the middle was crying. She was the only woman of hundreds that I saw crying while photographing their tour of the camp.” His photos were not only published throughout the world press, but also served as evidence in the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial.

After the war he returned to the U.S. He married in the early 1950s and became the father of a son on 17 July 1953. He initially worked for the Bethlehem Steel Corporation; later he moved to Florida with his wife Jean and their son Daniel. There he found employment as a material planner for the Jet Avion Company near Miami. After his wife passed away in the late 1990s, he moved back to Pennsylvania to be near his sister.Walter Chichersky died in a nursing home in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania on 14 April 2008.

Photographer unknown, ca.1943

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

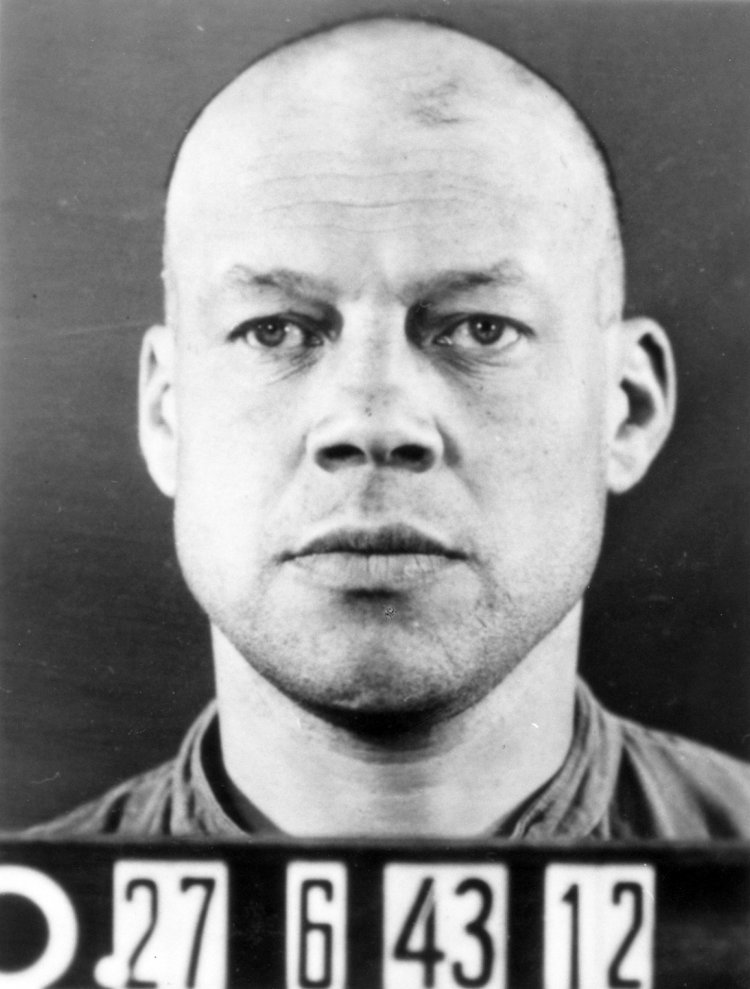

Rex L. Diveley

U.S. Army medical officer

17 June 1892 in Bazine, Kansas

24 November 1980 in Kansas City

The camera was not necessarily a part of his luggage and photography was not his calling. Rex L. Diveley participated in both world wars of the twentieth century in the role of a physician. It is not known how these experiences influenced or changed him; in any case, his life took an otherwise orderly and peaceful course.

Diveley grew up in Hutchinson, Kansas. Following completion of studies at the University of Kansas School of Medicine in 1917 he entered the U.S. Army medical corps, where he received training as a radiologist. Towards the end of World War I he was stationed in Limoges, France; in April 1919 he was discharged from military service with the rank of captain. He then carried out a residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, later going on to set up the radiology department of Mercy Hospital in Kansas City. In 1927, Dr. Diveley and his colleague Dr. Frank Dickson founded the Dickson-Diveley Orthopaedic Clinic in Kansas City, which would become one of the most renowned clinics in the American Midwest and a well-known training centre for orthopaedists. It still bears his name today.

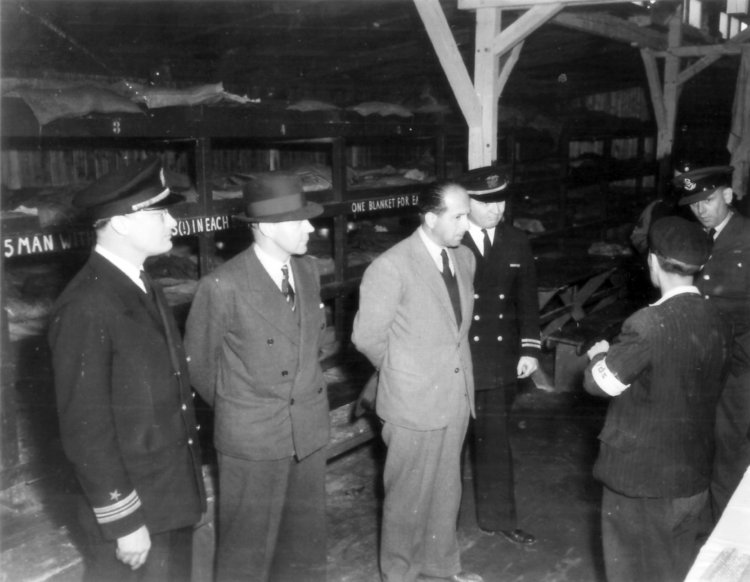

By the time he was once again summoned for service in the U.S. Army in 1942, at the age of 50, Dr. Diveley was an acknowledged specialist. In the rank of colonel, he served as the chief advisor for orthopaedic surgery in the Chief Surgeons’ Office of the European headquarters. In his capacity as head of the U.S. Army Rehabilitation Service he set up the first-aid system for disabled members of the armed forces. For his work he received the Bronze Star and the Legion of Merit. After the war, he continued to advise the army on issues of rehabilitation.

It is not known whether he ever talked about his impressions of Buchenwald later in life. He returned to his clinic in Kansas City, where he continued to work for many years. A research prize and a chair at the University of Kansas are named after him.

Photographer unknown, 1942

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

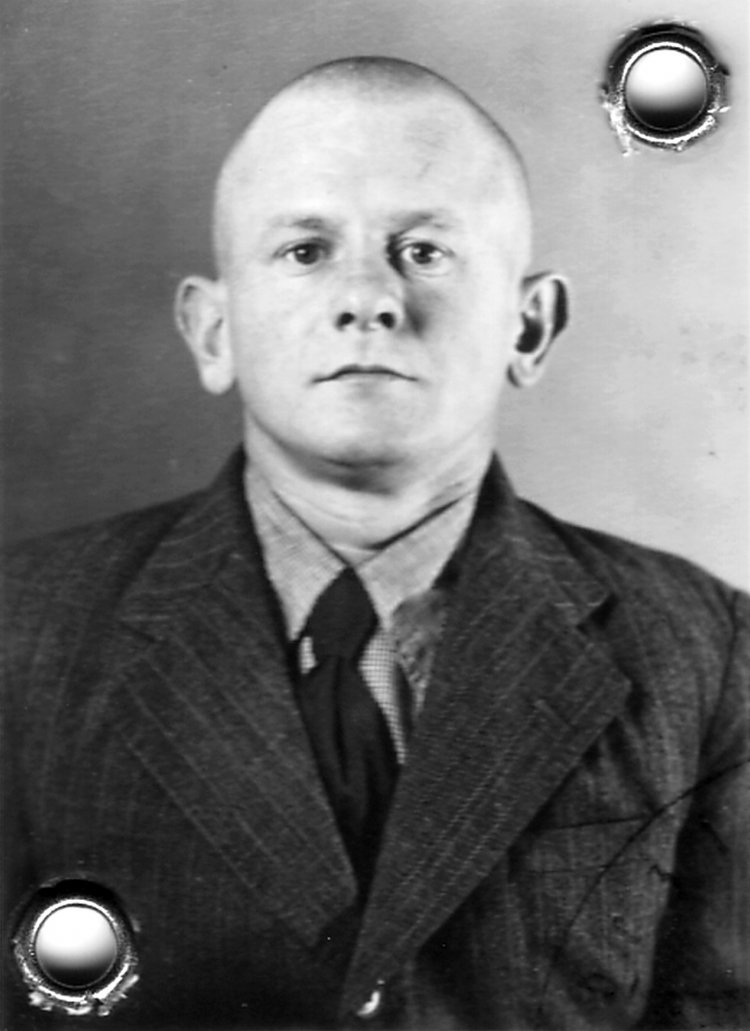

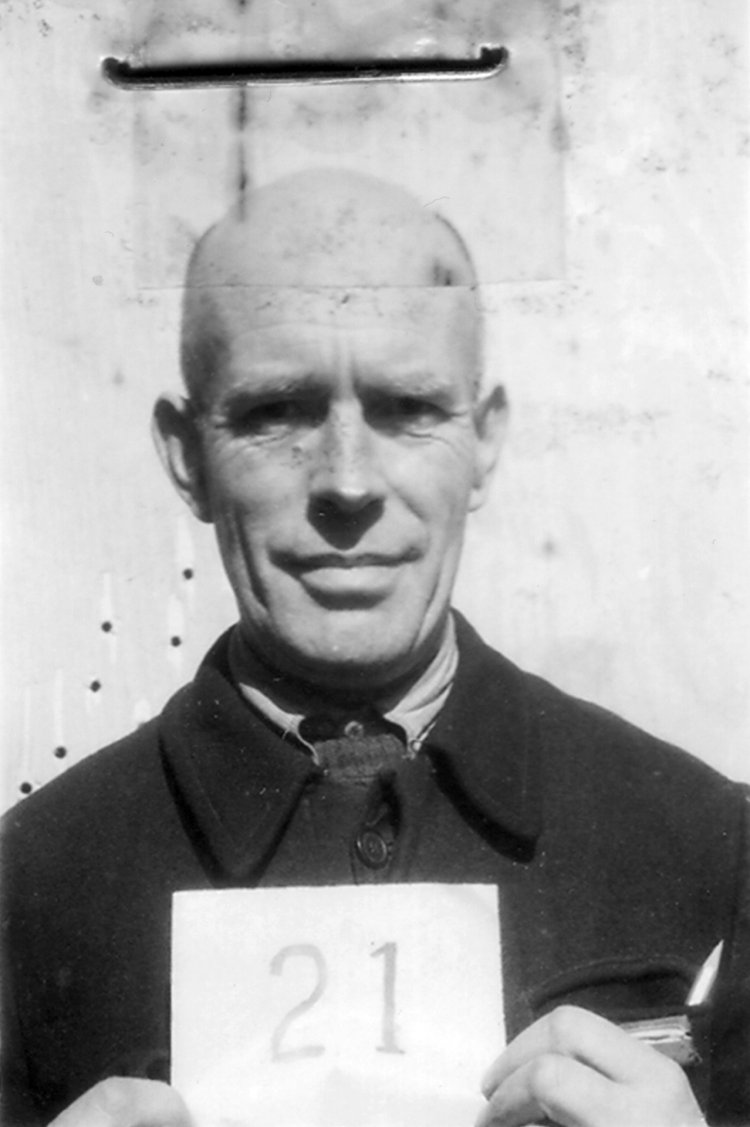

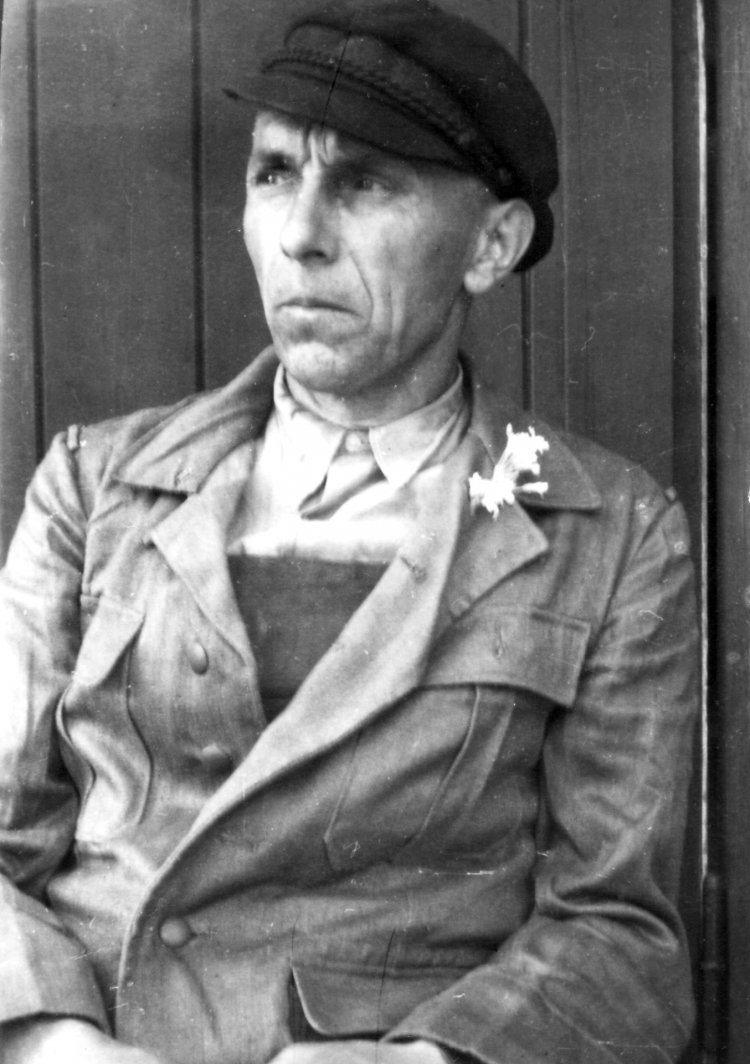

Adolf Dobschat

German political inmate

29 May 1900 in Pillkallen, East Prussia

8 July 1973 in Geraberg

Beginning as early as 1914 – when he began an apprenticeship as a bricklayer – Adolf Dobschat was involved in labour unions and political organizations. He was a member of the Freie Gewerkschaft (Free Labour Union) and, from 1917, the USPD (Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany). In March 1919, Dobschat participated in the Spartakus Uprising in Berlin. He joined the German Communist Party in 1920. On account of his involvement in the Ruhr Revolt in the spring of 1920, he was sentenced to an 18-month prison term and subsequently returned to East Prussia. There he devoted himself to establishing local Communist party branches, distributing leaflets, and organizing strikes and demonstrations. He served several prison sentences for his Communist activities.

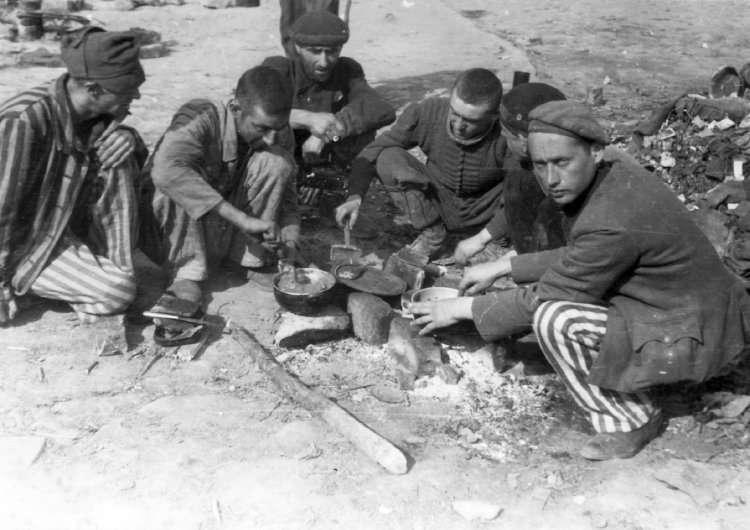

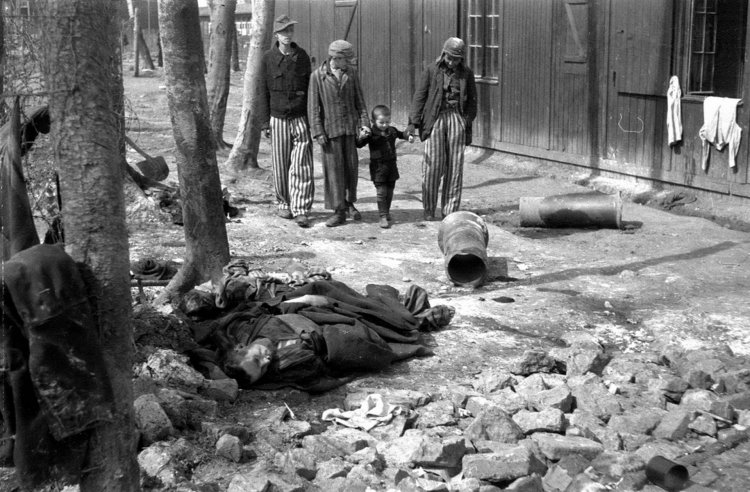

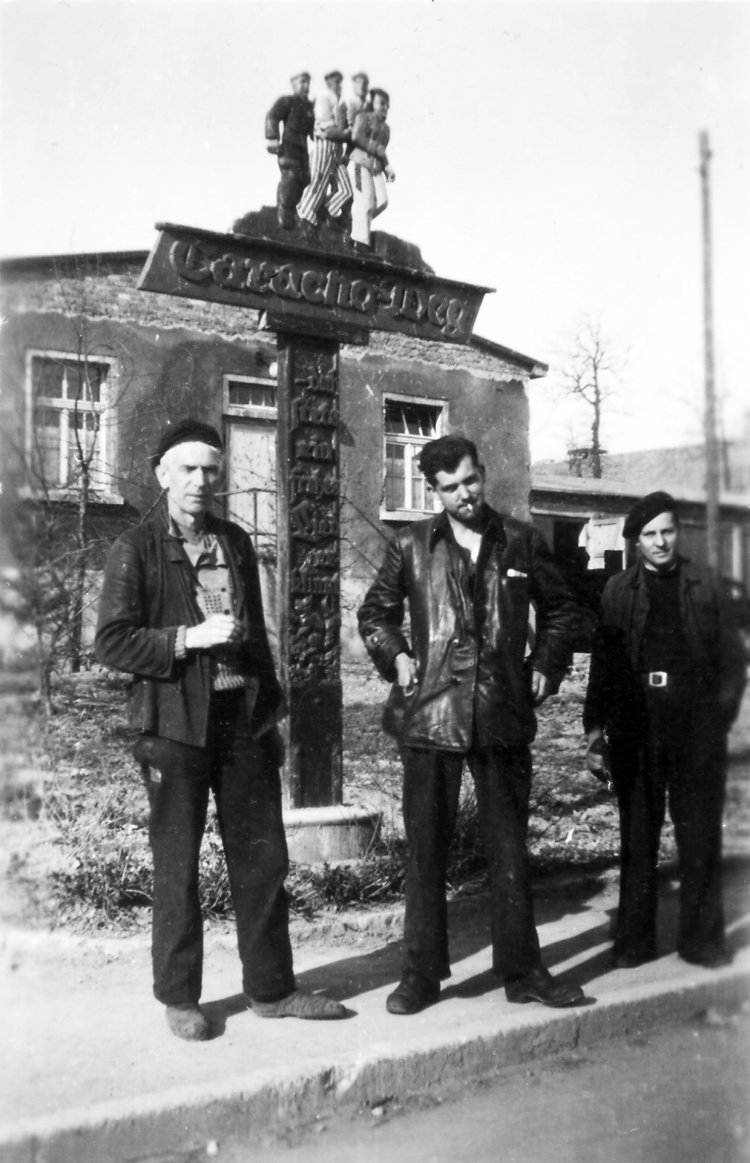

Adolf Dobschat was arrested yet again in March 1933, and in October 1936 sentenced to two years imprisonment by a special court in Königsberg on charges of preparations for high treason. He was subsequently committed to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In October 1941, he was transferred to the Buchenwald concentration camp, registered as a political prisoner, and assigned the inmate number 6592. He initially worked in the construction detachment, later in the depot of the inmates’ infirmary. A few days after the liberation of the camp in April 1945, Dobschat came into possession of a camera and took a series of at least 60 35mm photographs, primarily documenting political life in the liberated camp. He also took a few portraits of former inmates, in groups and individually.

Following his release, Adolf Dobschat remained in Thuringia. After a brief period working as a bricklayer in Berlstedt, he found employment with the Geraberg forest office and served as a district ranger until his retirement.

Photographer unknown, 1 May 1945

Private collection

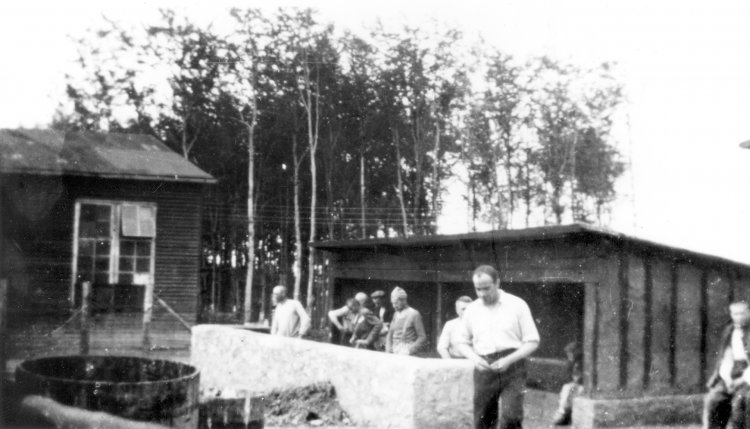

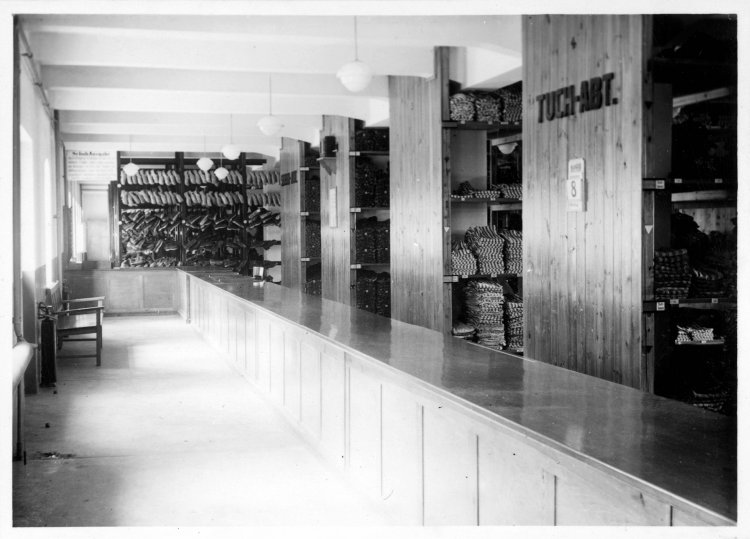

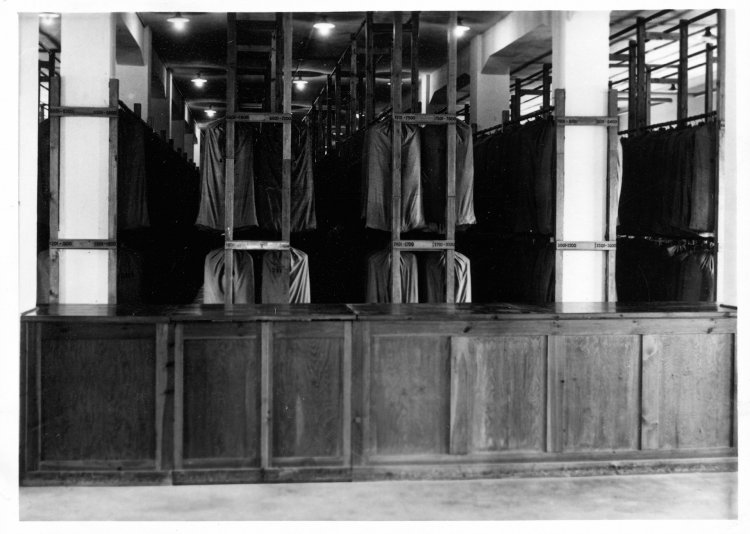

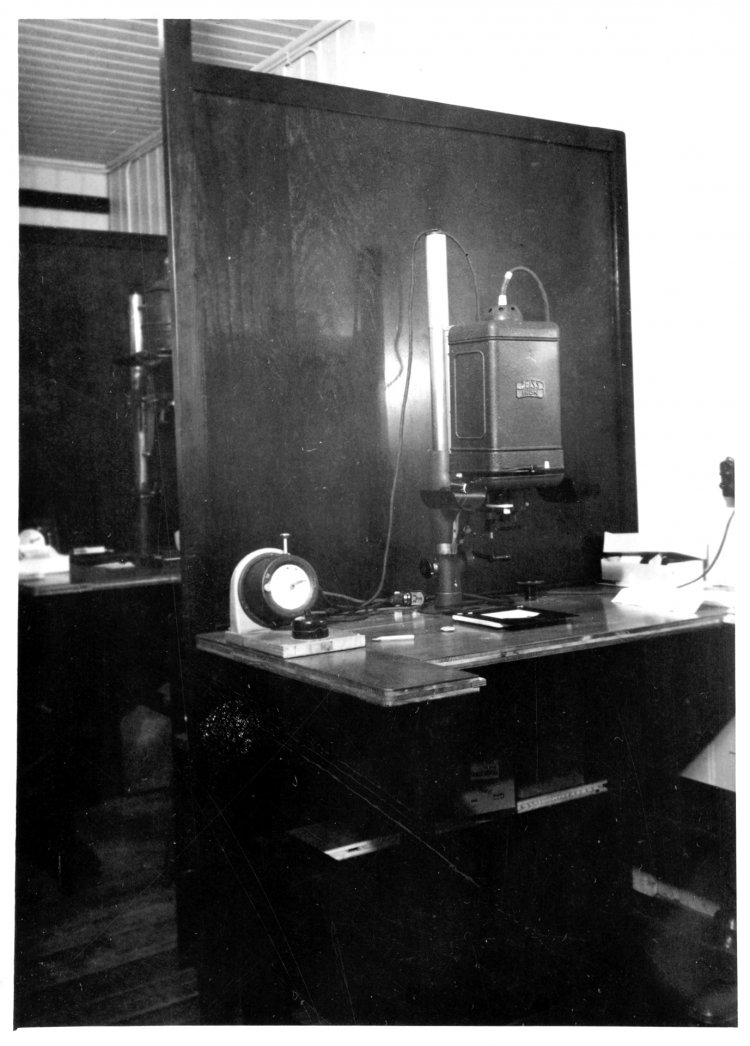

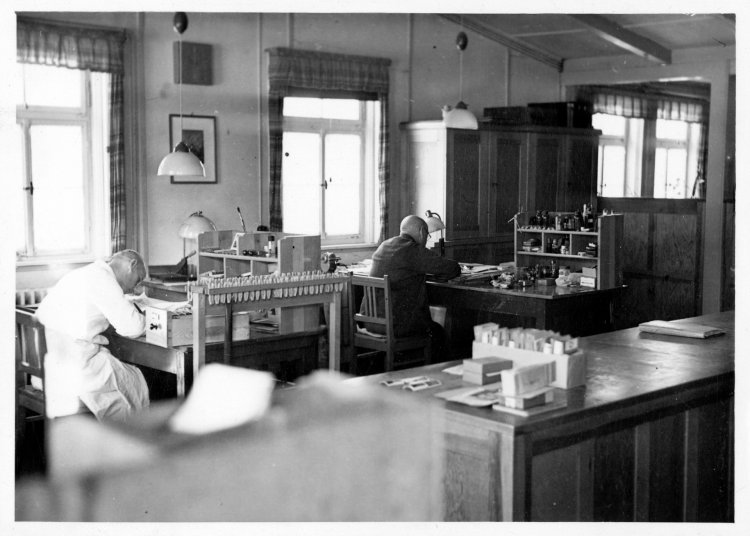

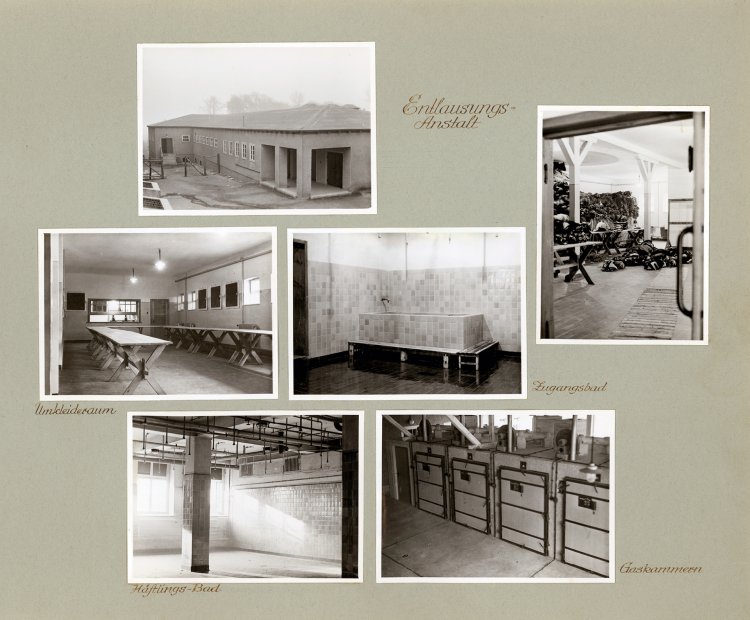

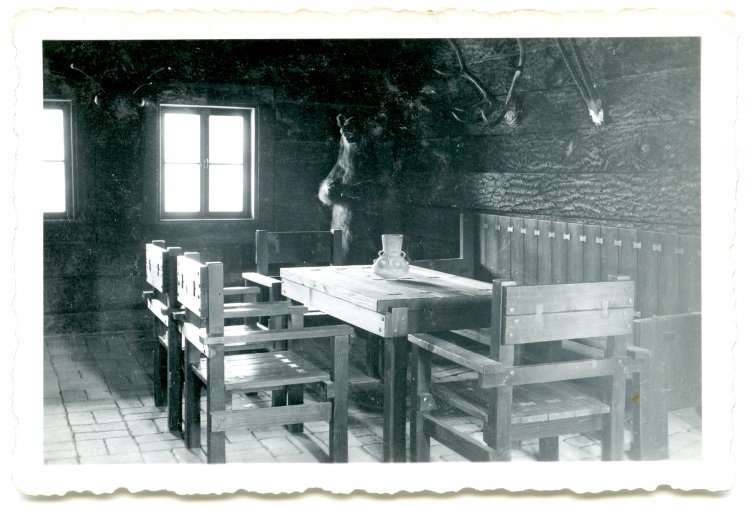

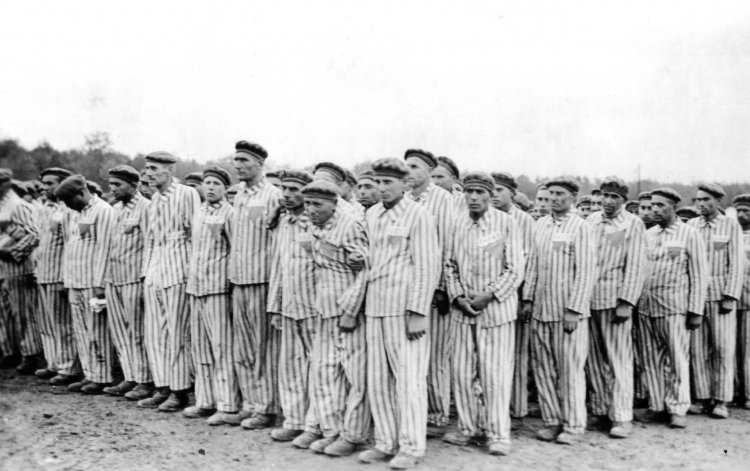

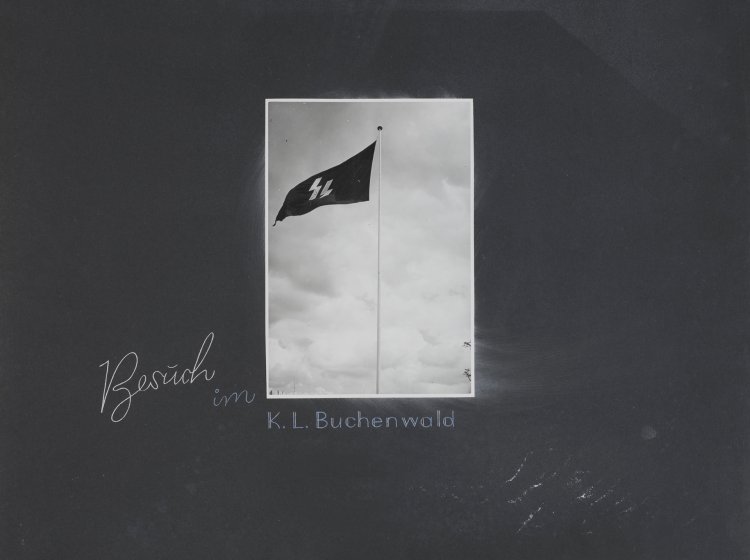

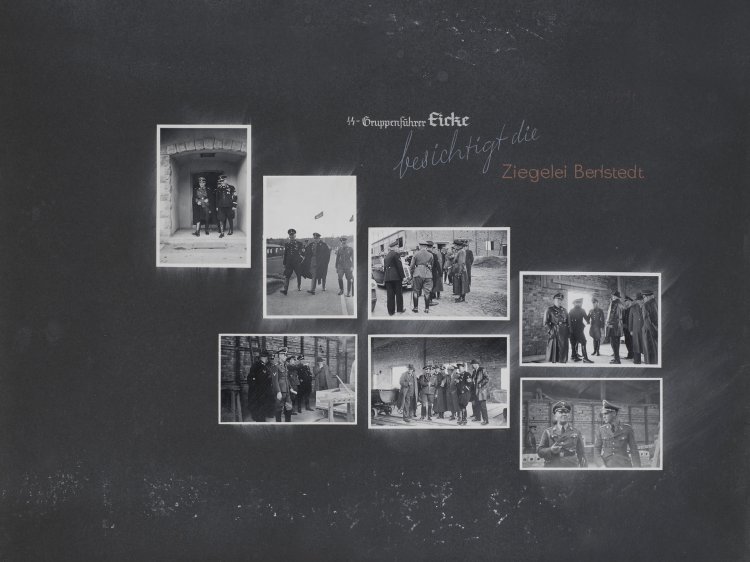

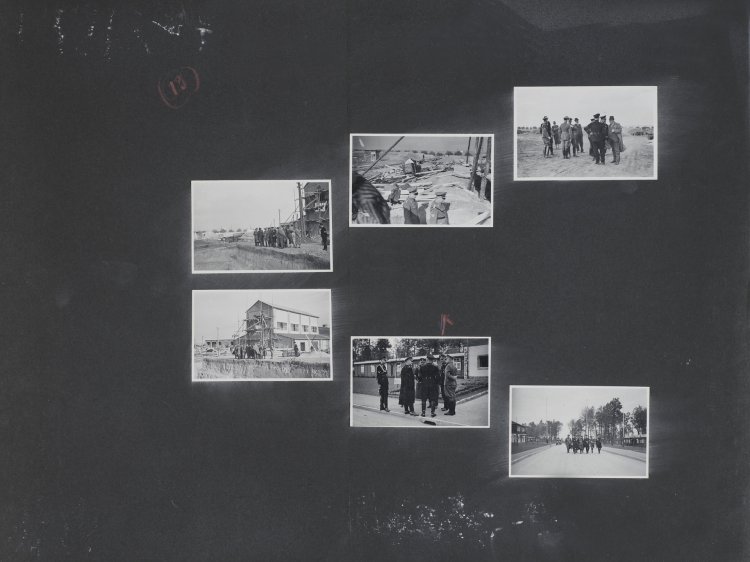

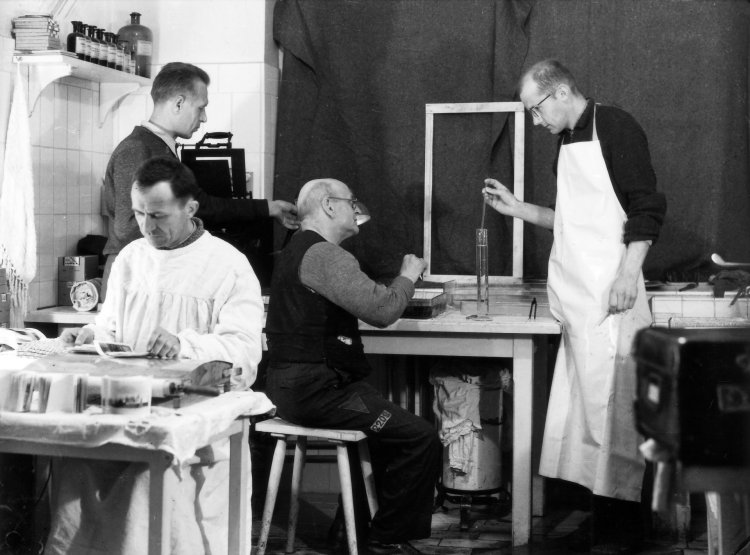

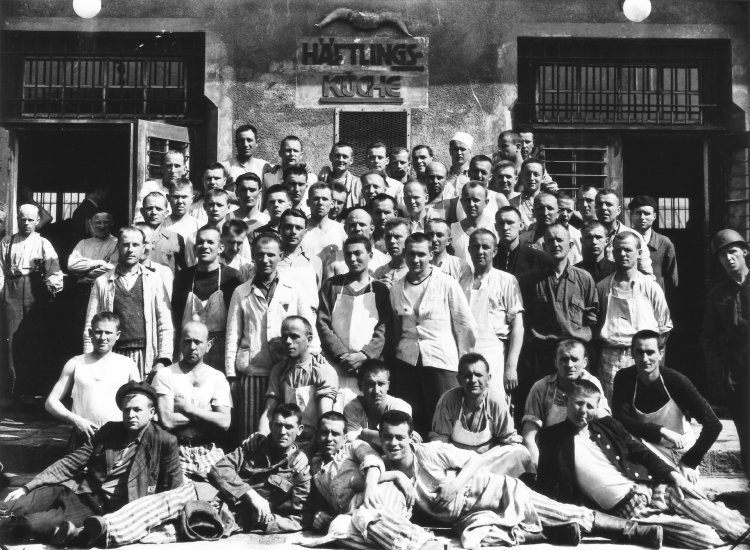

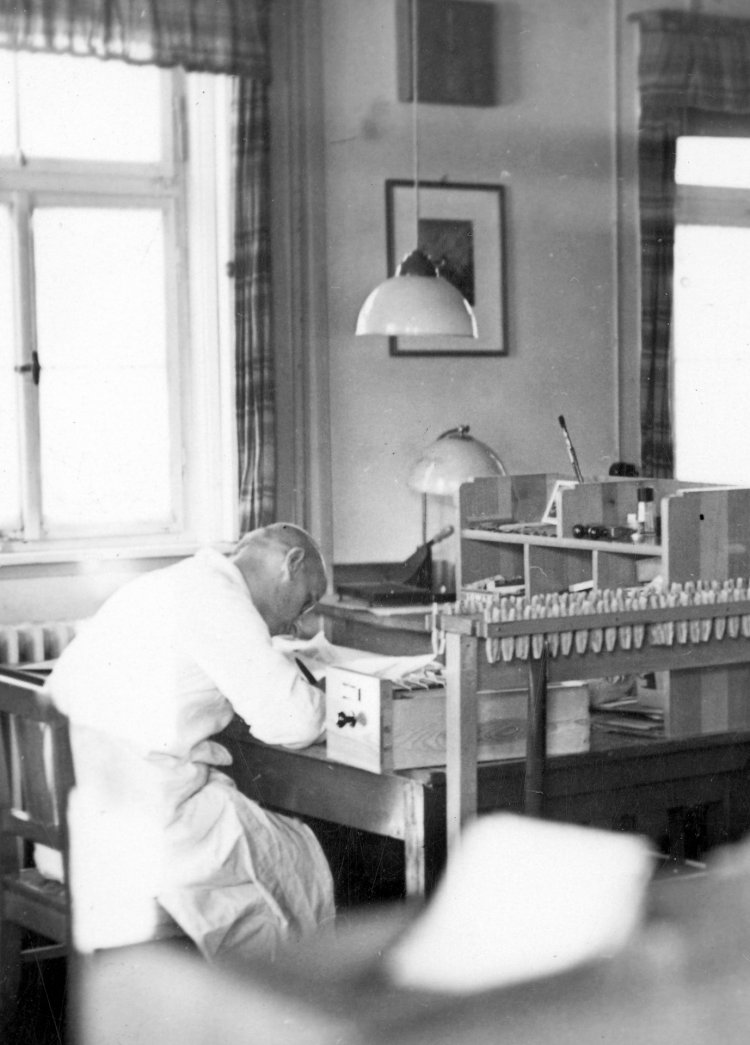

Buchenwald concentration camp records office

The records office was a very modern department with its own photo lab. Its most important task was the registration of the arriving inmates for the inmates’ card file. In addition, it photographically documented suicides, accidents, and executions as well as special camp events such as SS festivities, took portraits of SS men and their wives, and made copies of the SS families’ private photos.

As many as 13 German and French inmates worked here under SS supervision. The first kapo of the photo department detachment was the German political inmate Rudolf Opitz, who held this office until his murder in August 1939. His successor was Eberhard Leitner. The majority of the German inmates in the detachment were Jehovah’s Witnesses, who had the reputation of being highly reliable. Their job was to take pictures, develop film, and enlarge the images in the darkroom. In cooperation with the bookbinding detachment, they made a great number of private and official photo albums for the SS.

In the early years of the camp’s existence, after changing hands several times, the position of head of the records office was assumed by SS Oberscharführer Hubert Peitz. The records office barrack was hit so badly during the Allied air raid of 24 August 1944 that it could subsequently no longer be used. The majority of photos kept there were destroyed by fire on the day of the attack.

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

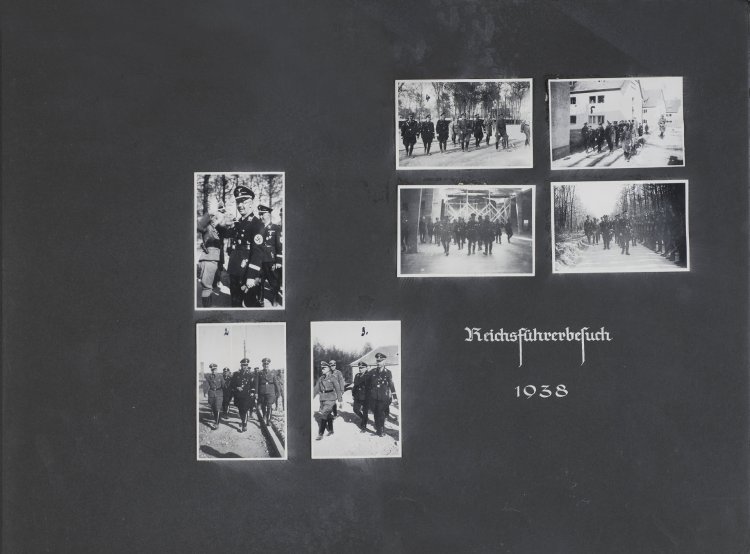

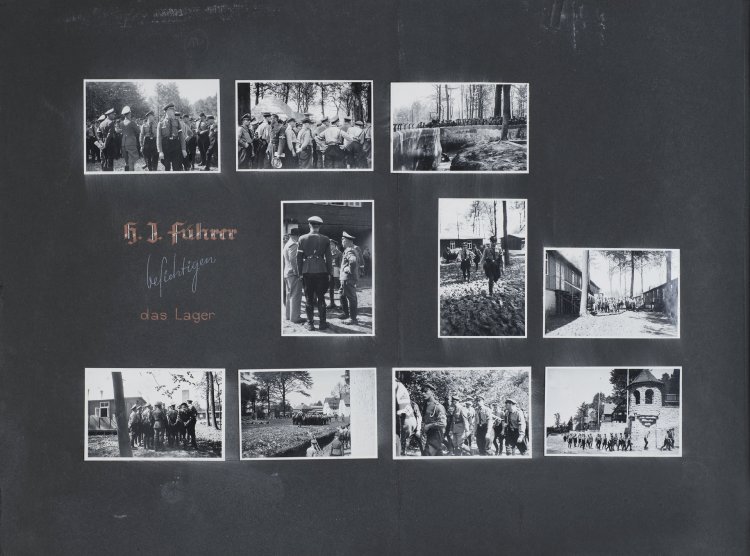

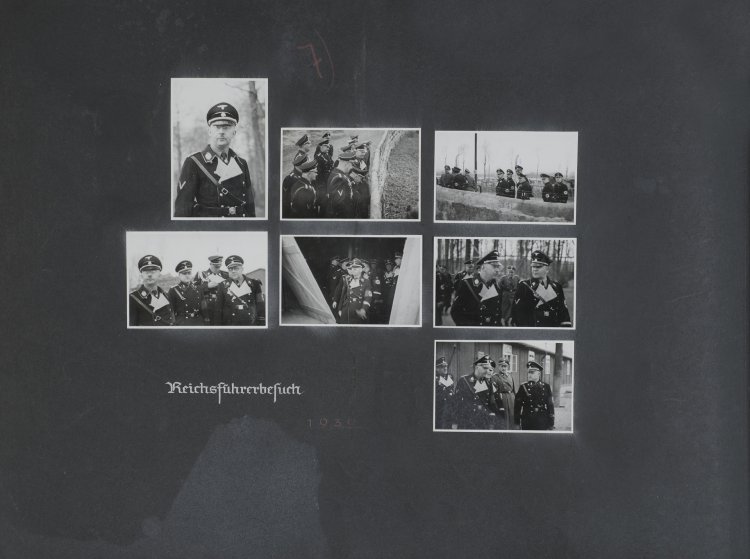

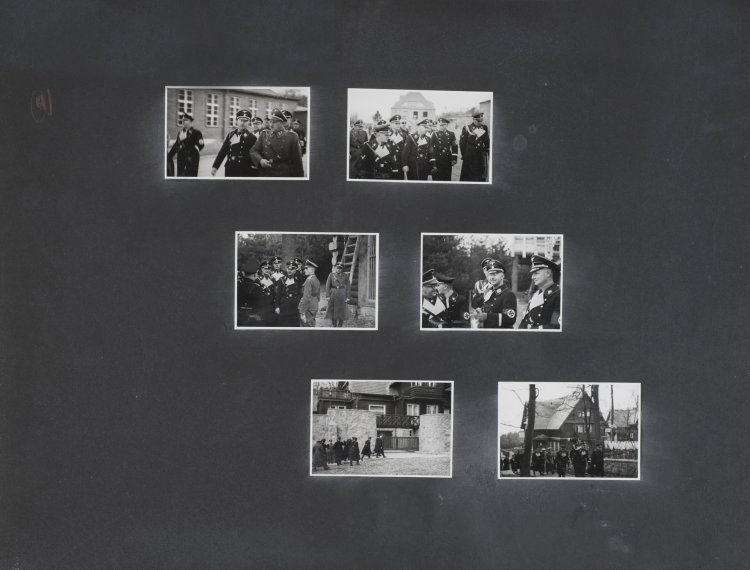

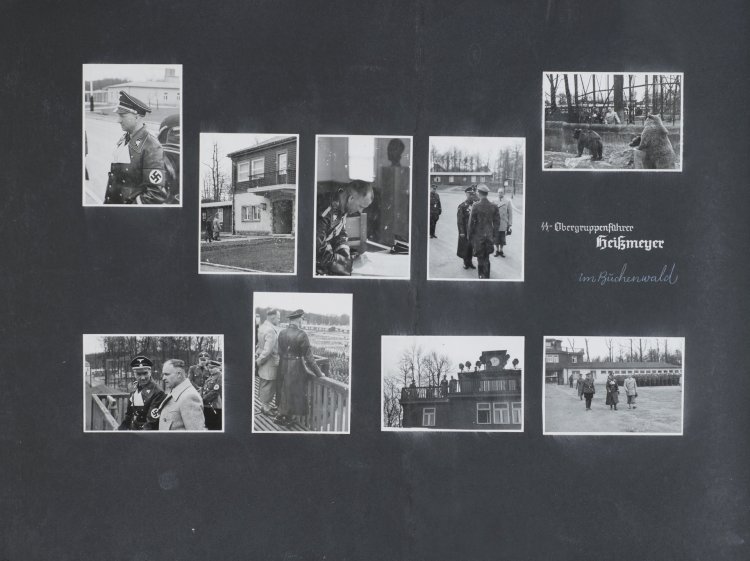

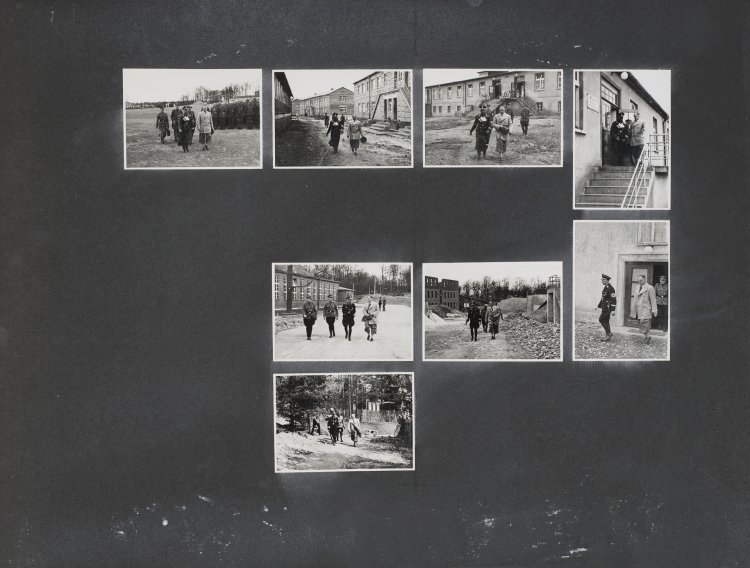

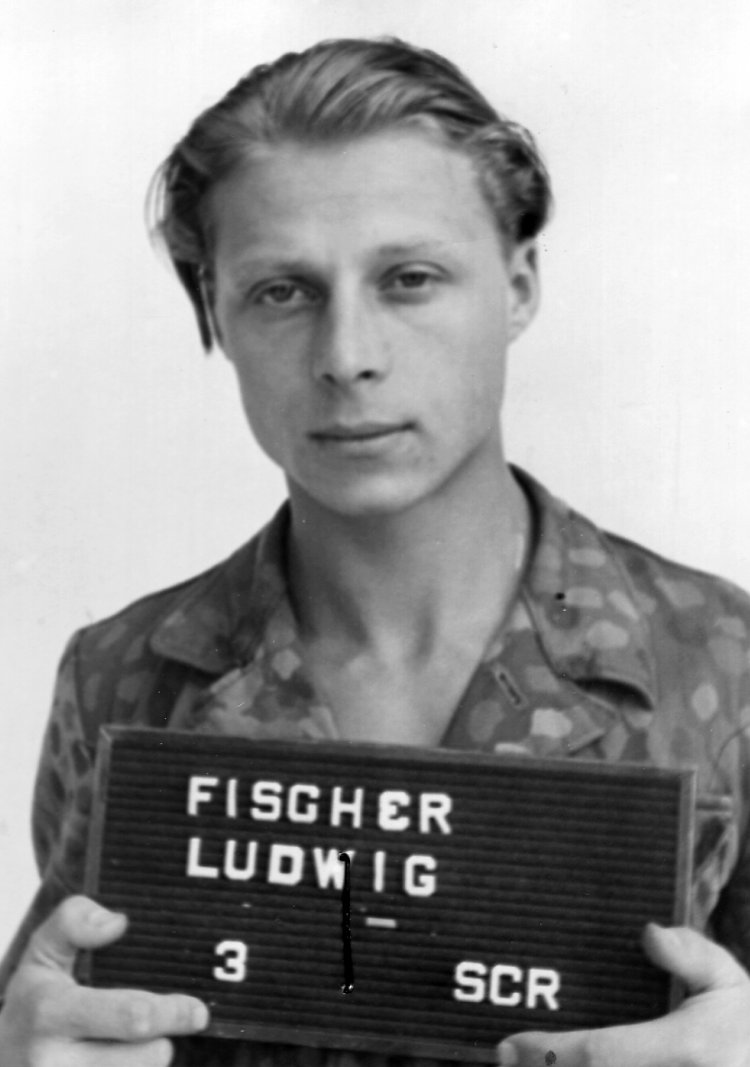

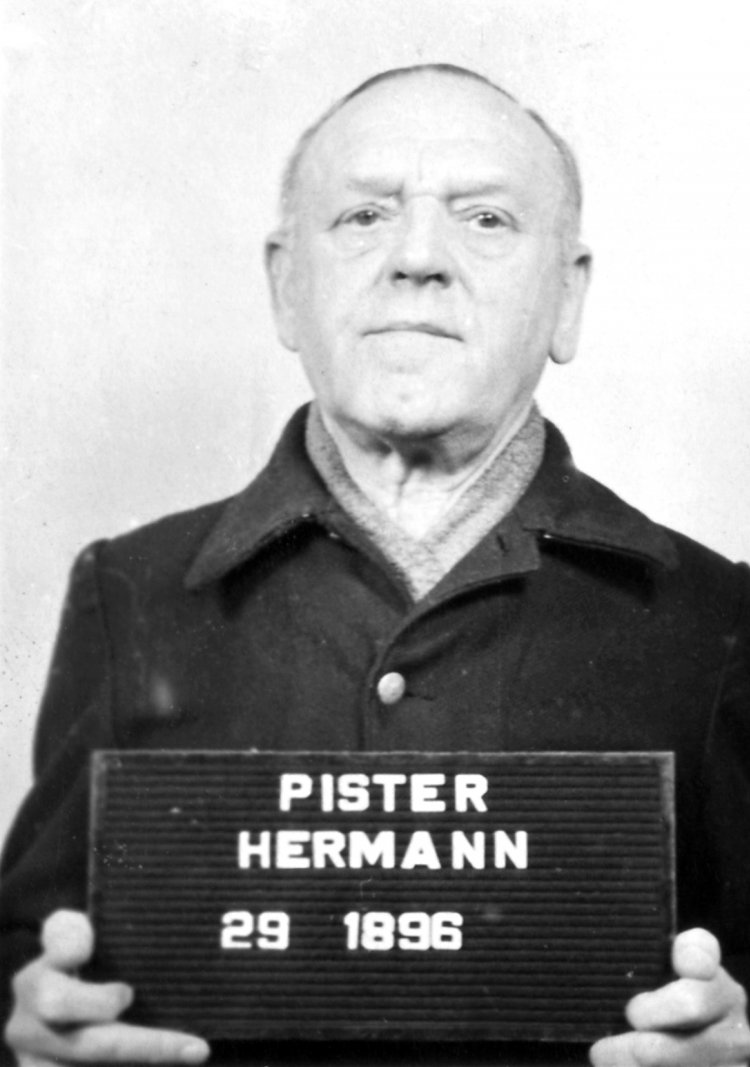

Karl Hänsel

SS Unterscharführer

13 December 1913 in Schleusingen

23 February 1949 in Landsberg am Lech

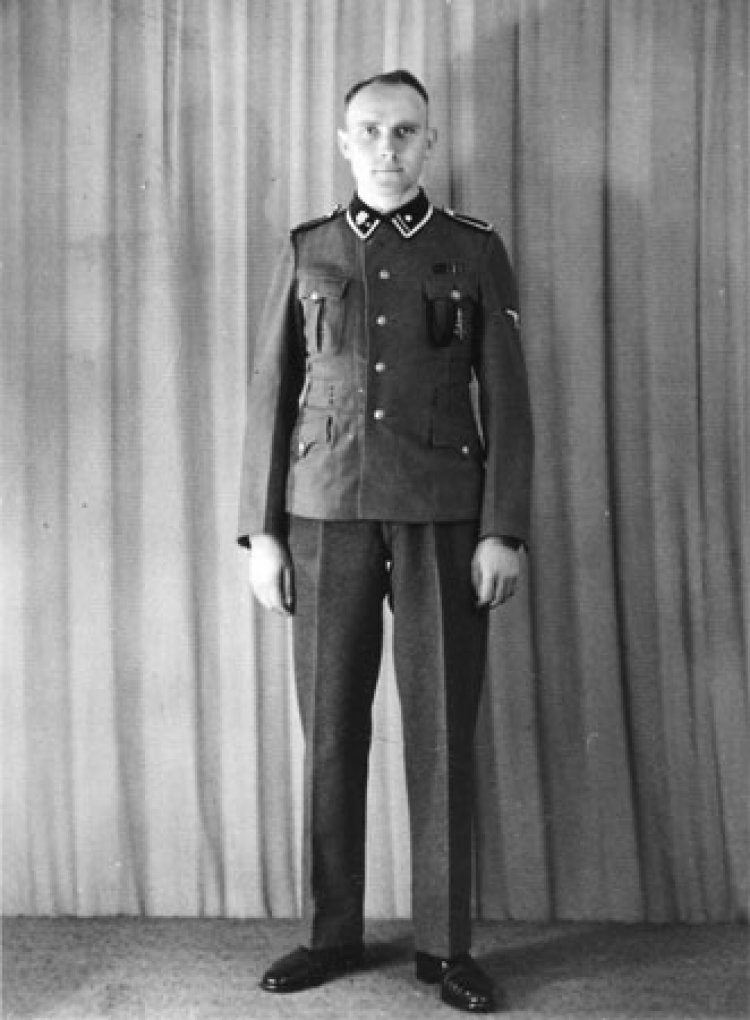

Upon completion of his schooling, Karl Hänsel learned the profession of stove fitter and passed his journeyman’s exam in 1931. In December 1932 he joined the SS, where he was assigned the number 67.405. Beginning in March 1934 he served as a guard at SS headquarters in Weimar. In April 1936 he was promoted to the SS Totenkopf Battalion “Elbe”. In July of 1937 he was admitted to the Third SS Totenkopf Regiment “Thüringen”.

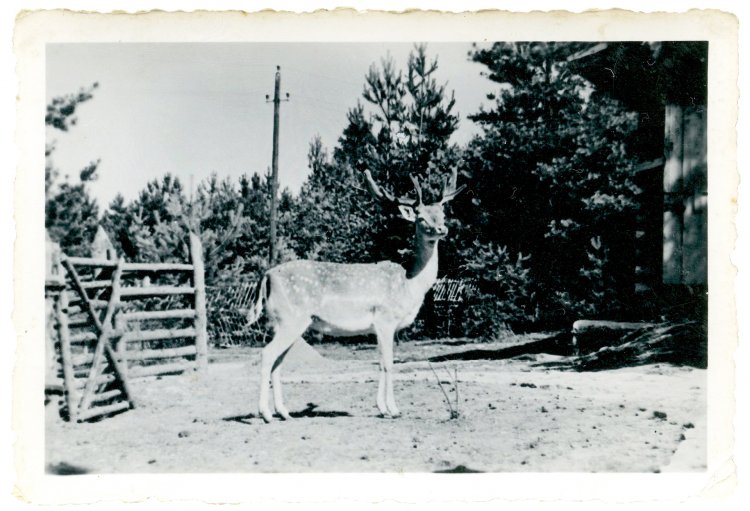

During this period, a number of pictures were taken at the Buchenwald concentration camp in the context of visits Hänsel made to his comrades in the SS guard units. These photographs were intended as private keepsakes, and Karl Hänsel later pasted them into a photo album. In September 1938 he was transferred to the SS command staff of the Flossenbürg concentration camp to serve as a block and labour detachment officer. He rose to the rank of SS Hauptscharführer in April 1942. In February 1945, he volunteered for front service in the German Wehrmacht.

Arrested by the Allies after the war, he was among the co-defendants in the Flossenbürg Trial carried out by the Americans in Dachau. In November 1947, Hänsel was sentenced to life imprisonment; he died in the war criminals’ prison in Landsberg am Lech in 1949.

Flossenbürg concentration camp records office, 1938

Bundesarchiv, Berlin

Francis D. Killin

U.S. Army soldier

28 May 1923 in Fillmore, Missouri

13 June 1988 in St. Joseph, Nebraska

Francis D. Killin was born in Fillmore, Missouri in May 1923. He entered U.S. military service at the age of 19 in conscious adherence to a family tradition that dated back to the American Civil War. With the 37th Armored Cavalry Reconnaissance (V-Corps) unit under Major General Courtney Hodges, he participated in the invasion of Normandy at Omaha Beach and then made his way to Germany via France and Belgium. He was wounded near Liège and just barely escaped being taken prisoner of war by the Germans.

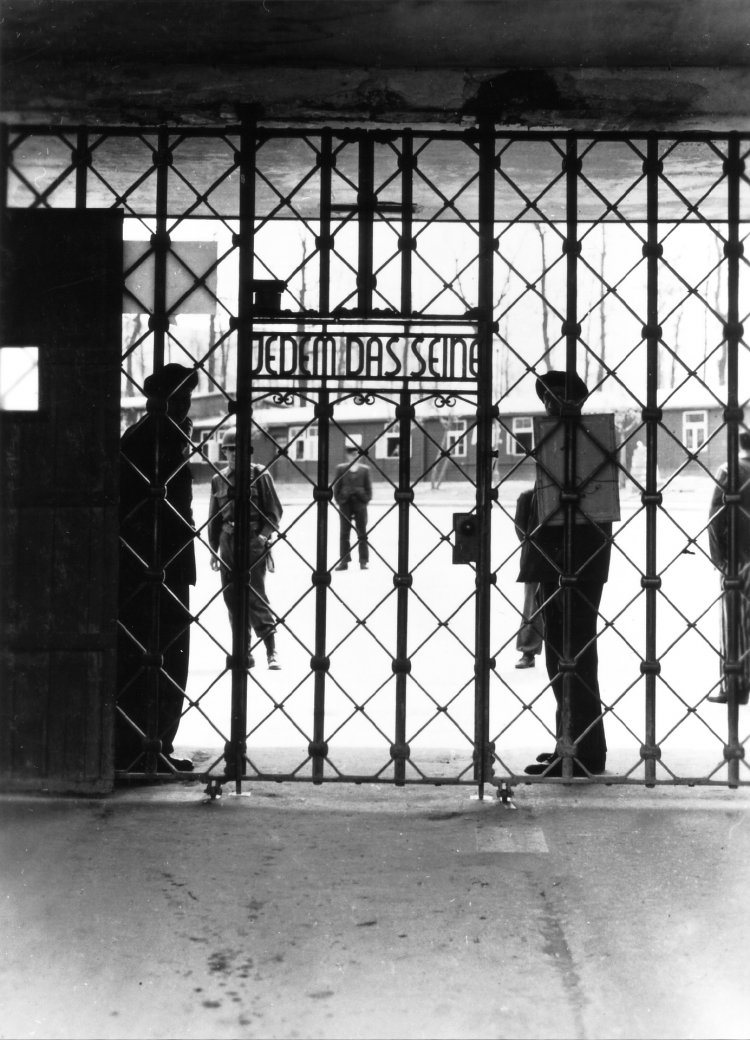

In April 1945, Francis D. Killin’s unit reached the Buchenwald concentration camp. With his little Kodak camera he documented the tours of the camp organized for military and civilian visitors: the camp gate, the muster ground, the crematorium, and the heaps of corpses. Yet Killin did not limit himself to photographing the sites shown to him and his fellow soldiers, but also pointed his lens at his comrades, recording their reactions, gazes, conversations, and silence.

After the war, Francis D. Killin left the U.S. Army. He married in the spring of 1946, became a father to three sons and three daughters, and held a high-ranking post in a construction company.

He did not have his pictures developed for nearly 20 years. According to his son, Francis D. Killin felt incapable of conveying his war experiences, particularly those he had had in the liberated Buchenwald camp. “The pictures were a burden on my father until his death. It troubled him that he met people who denied the Holocaust; he had seen the horrors and a few of the persons responsible for them in Buchenwald.” Francis D. Killin marked a number of the snapshots “Do Not Duplicate” on the back. It was only after his death on 13 June 1988 that – in 1993 – one of his sons made the photos of Buchenwald public on the “Virtual Jewish Library”.

Photographer unknown, 1945

Private collection

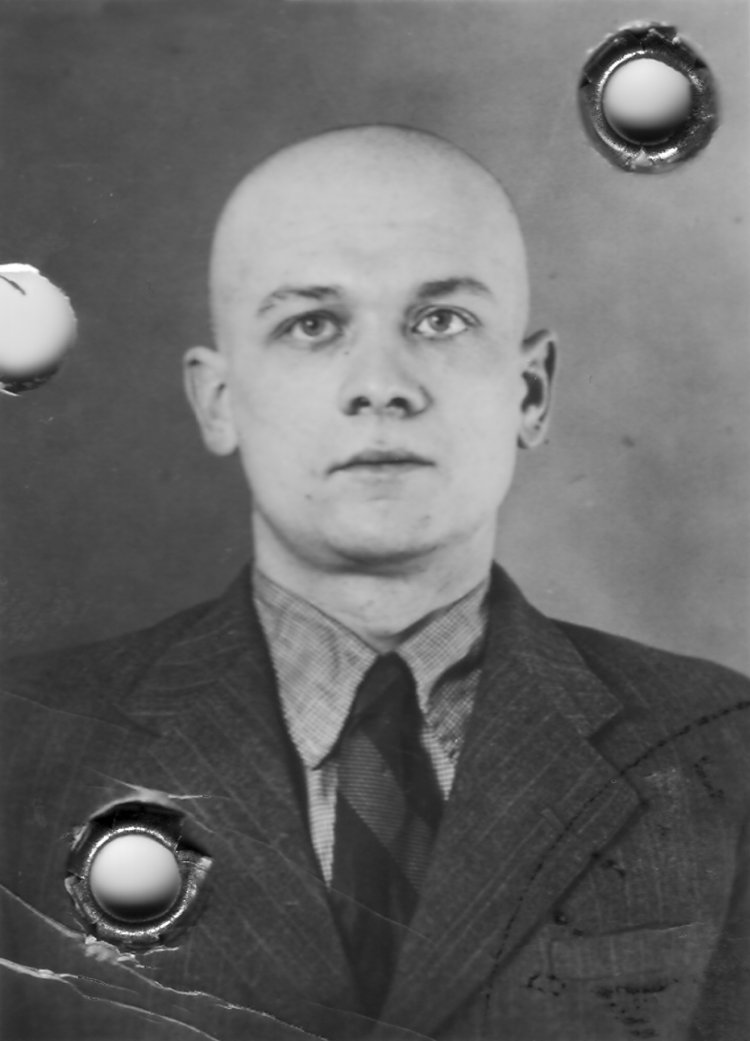

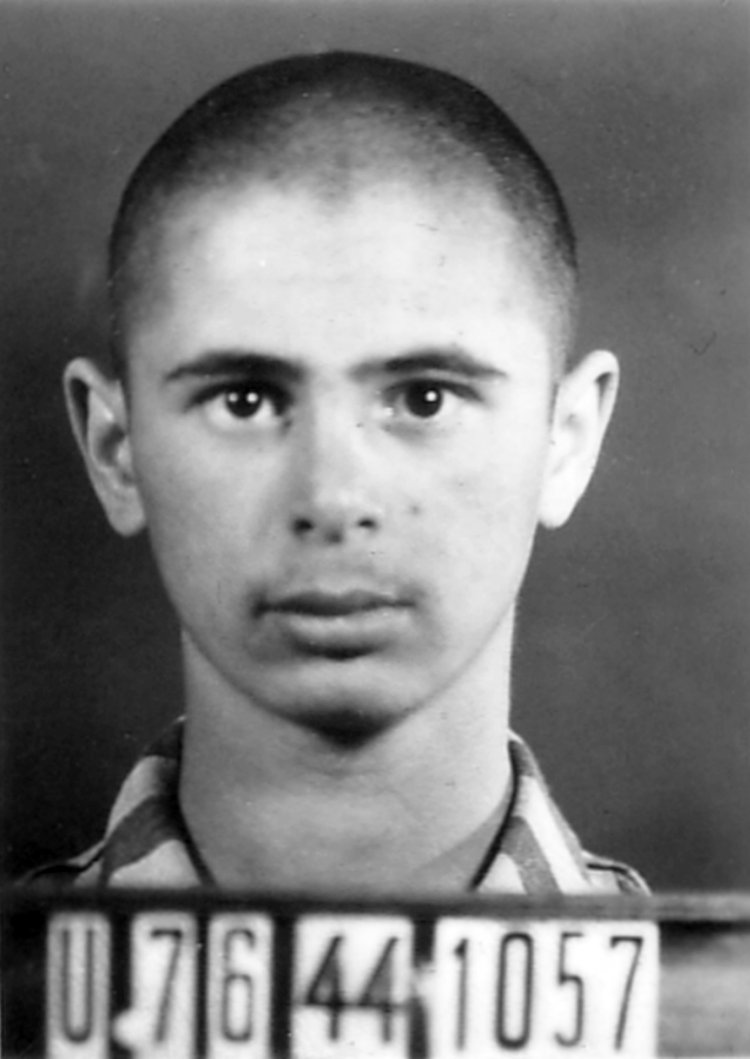

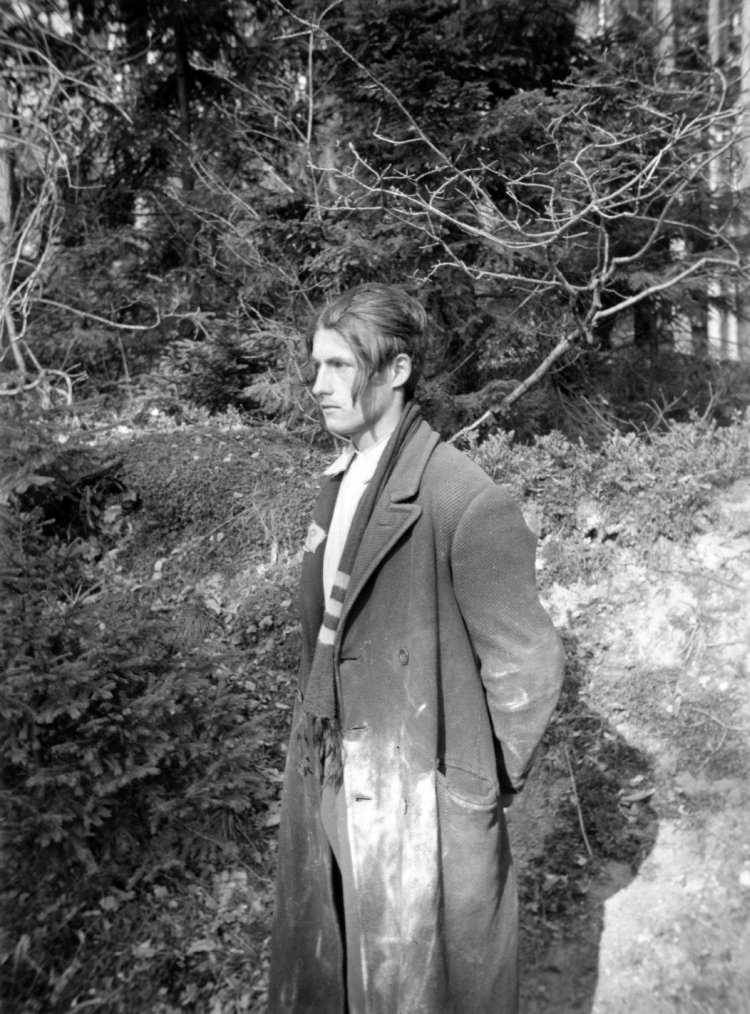

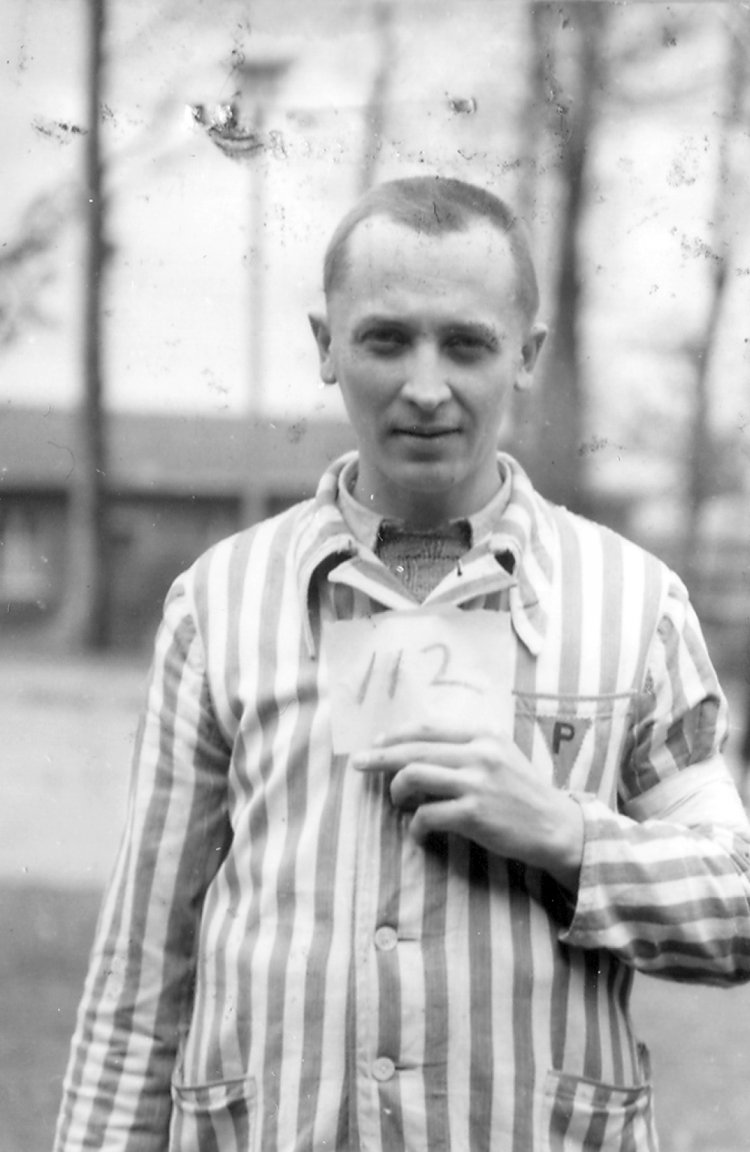

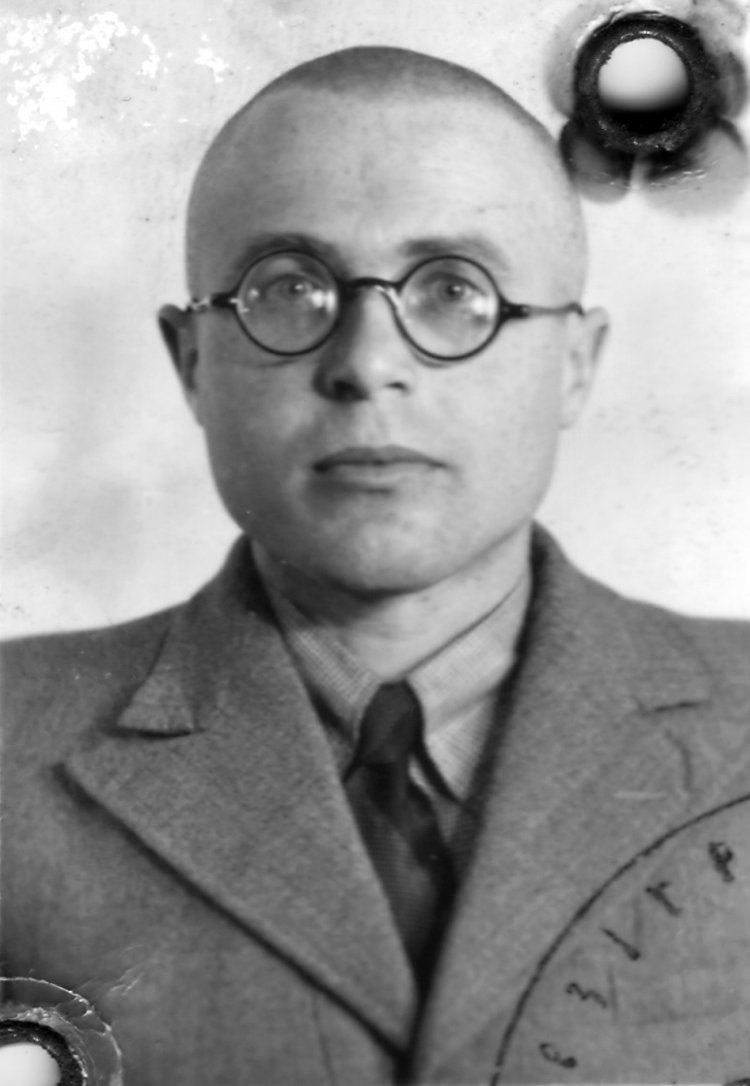

Eberhard Leitner

German political inmate

15 June 1907 in Garnberg

1 November 1991 in Freiburg im Breisgau

After passing his school-leaving examination in 1926, Eberhard Leitner, nicknamed Edo, studied art history in Tübingen and Heidelberg. In 1928 he transferred to the school of applied arts in Stuttgart and had already begun working as a photographer and commercial designer by the end of the decade . In March 1933, shortly after Hitler’s seizure of power, he was arrested as a member of the German Communist Party and confined in the Herzberg concentration camp for five months. In 1936 he was arrested once again, and in 1938 was committed to Buchenwald after serving time in penitentiaries in Stuttgart and Ulm as well as in the Welzheim concentration camp. In Buchenwald he was registered as a “politically recidivous” inmate under the number 210.

Edo Leitner participated in the camp resistance activities. Beginning in 1939 he worked in the inmate labour detachment referred to as the “photo department”, becoming its kapo in 1940. There he was required to take pictures of arriving inmates for the records office on behalf of the SS, and to document – among other things – suicides and medical experiments. The entire inventory of photos, including many he clandestinely put aside, was destroyed by fire during the Allied air attack of 24 August 1944. Edo Leitner also served as a film projectionist in the camp, showing German feature films and newsreels at the behest of the SS. He was in charge of the cinema barrack, in which the resistance organization installed an illegal radio transmitter. After the liberation, he was excluded from the camp chapter of the German Communist Party for allegedly destroying a radio receiver in 1944.

Following liberation, the photo department took a series of photographs of the camp and copied them in great numbers; they were in the baggage of many a survivor returning home. After the war, as a member of the Association of Victims of the Nazi Regime, Edo Leitner put together slide lectures which he held primarily in Baden-Württemberg. He was active in the peace movement until his death in 1991.

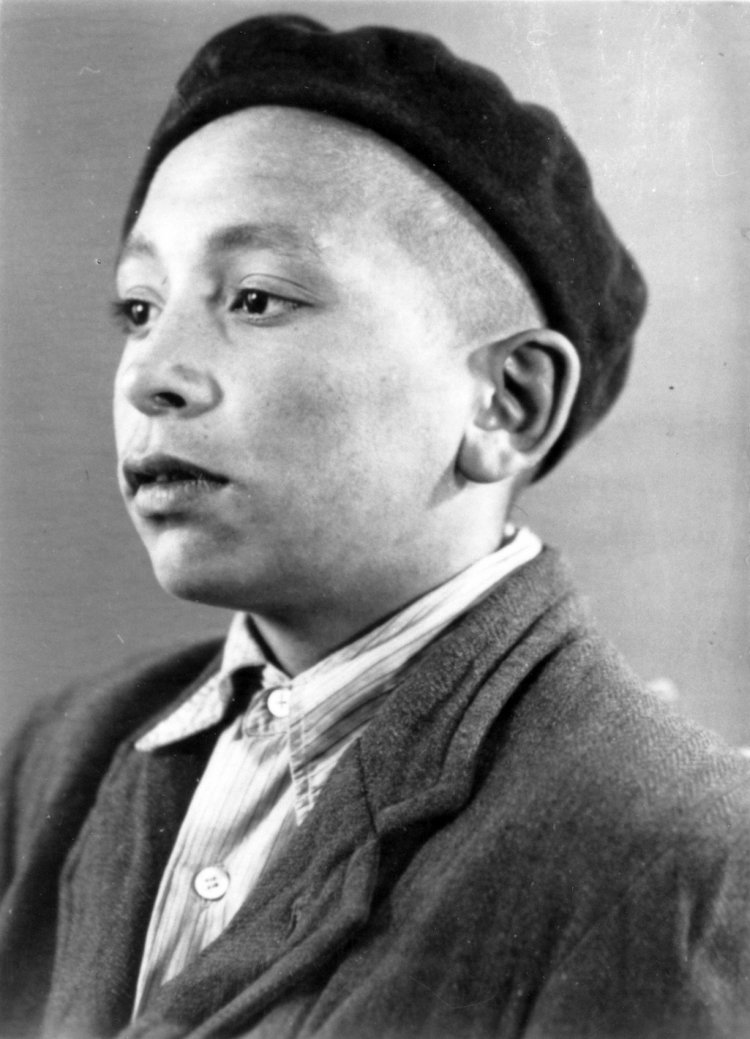

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, September 1939

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Armin Meisel

Local resident

30 March 1922 in Gaberndorf

17 December 2011 in Gaberndorf

His parents were farmers in the small town of Gaberndorf outside Weimar. The streets were still unnamed; they lived in house no. 100. Already as a teenager, Armin Meisel was interested in photography. For his 15th birthday he received a Voigtländer “Bessa”, a simple bellows camera for roll film. He began using it to take snapshots of all the village events – baptisms, annual fairs, weddings, etc. – as well as the landscape of Ettersberg Mountain, at whose foot Gaberndorf was situated.

After the Buchenwald concentration camp was built in the summer of 1937 in the Ettersberg forest only three kilometres from Gaberndorf, Armin wanted to get a closer look. When the SS guards threatened to shoot him, he ran away. “Then I knew what was in store for the prisoners here”, he later recalled. Soon the concentration camp, the SS at the village fairs, and – from the summer of 1939 onwards – the inmates were all familiar sights. Every morning, the inmate waterworks detachment marched from the Buchenwald concentration camp to Daasdorf by way of the Gaberndorf village road and back again in the evening. In Daasdorf the inmates were laying water supply lines for the SS caserns. Most of the villagers were indifferent to the figures in their striped uniforms; some watched, none showed pity. Seventeen-year-old Armin Meisel was a little scared, but we wanted to take a picture of the work gang. He waited for a day when the weather was good, and when he saw the gang coming, he hid in his parents’ house. He estimated the distance and set the camera accordingly; at the right moment he made the exposure through a window from the safety of the attic. He had the picture developed at a photo shop in Weimar but never showed it to anyone. When Armin Meisel was called up for service in the Wehrmacht in 1941, he was sent to Russia and the Eastern front. He took his “Bessa” along, but soon lost it. Upon his return to Gaberndorf, he continued his activities as village chronicler. He worked as a farmer and accountant in an agricultural production cooperative. Even long after his retirement, he continued to photograph important events in Gaberndorf. Armin Meisel died in 2011.

Marko Priske, September 2008

Private collection

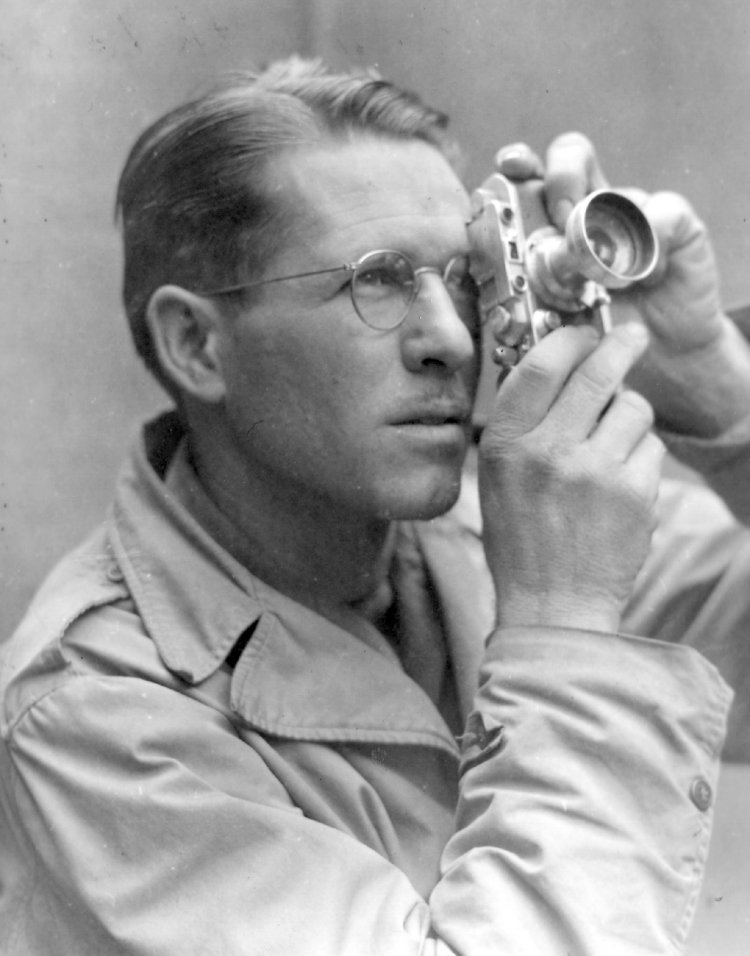

Ardean R. Miller III

U.S. Army photographer

20 September 1915 in Rochester, New York

1984 in Miami, Florida

Ardean R. Miller III was one of the first photographers in the service of the American army to work in colour. He attended Hobart College and the Rochester Institute of Technology. Following completion of his studies, he worked as a photographer for the advertising department of Eastman Kodak. In 1937 he received the Leica Award for Excellence; in 1939 his photos were featured at the World’s Fair in New York.

Miller volunteered for military service but was deferred because of a sight impairment. He was drafted in 1941. On account of his professional experience he was transferred to the Army War College in Washington D.C. and put to work photographing American army bases. He specialized in very large-scale colour photographs. In 1943 Miller went to Europe, initially to photograph the preparations for the invasion in England. In that context he collaborated with Albert Norris Stevens. In the years that followed, Miller’s photographic subjects included Generals Eisenhower and Spaatz, the first encounter between American and Soviet troops in Torgau on 25 April 1945, and the German surrender in Reims on 7 May 1945.

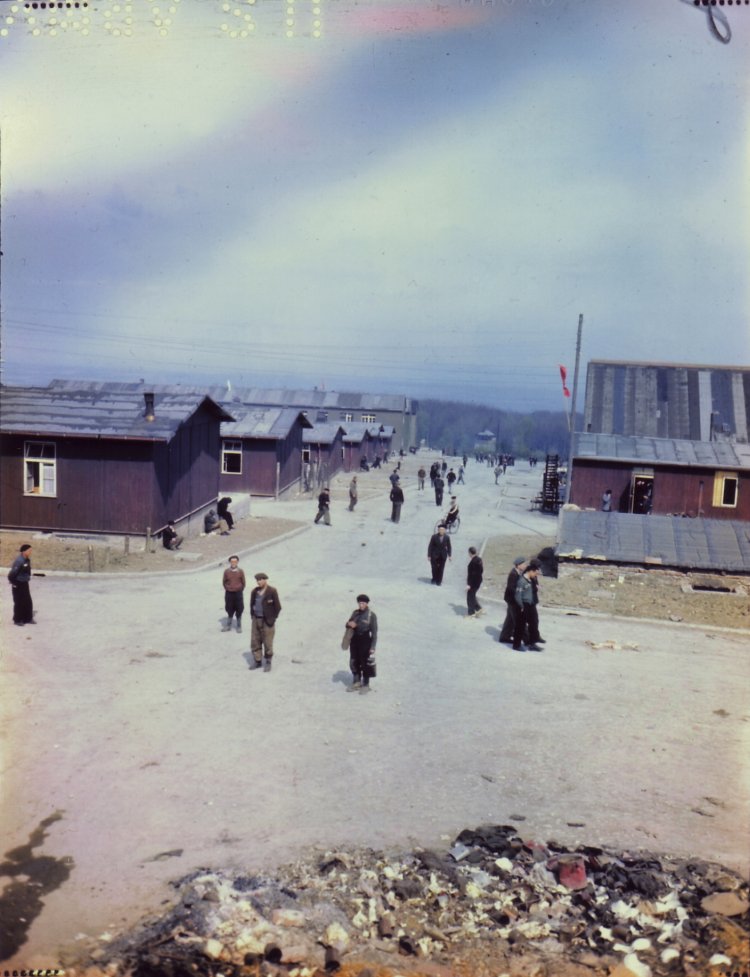

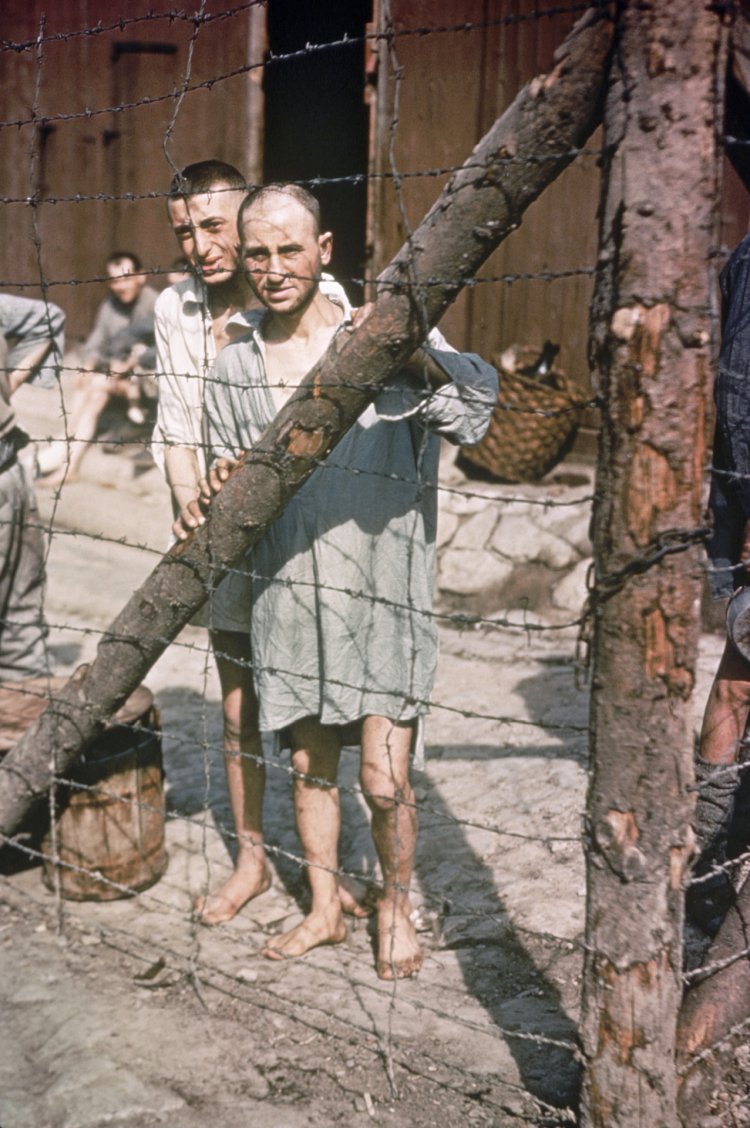

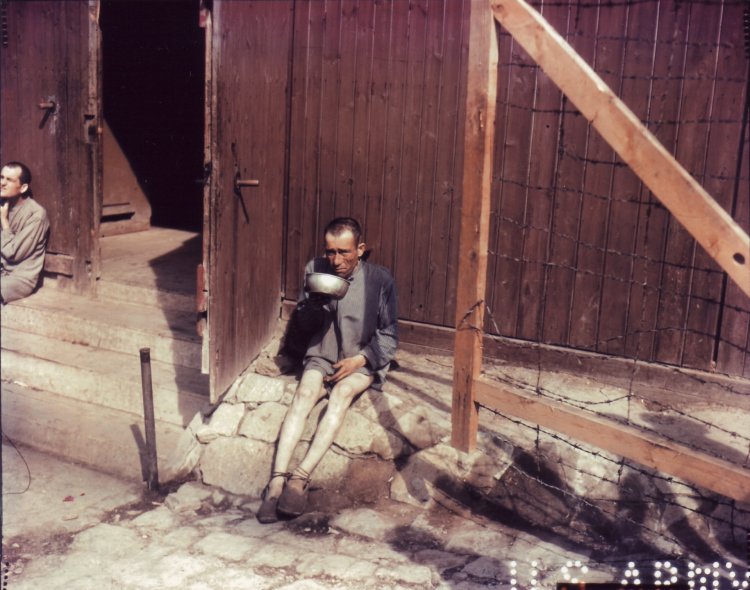

He later referred to his assignment to photograph the liberated Buchenwald camp as the worst he had ever faced in his career. On 18 April 1945, a week after the liberation of the camp, he took a series of colour photos there. According to his wife Norma, he only rarely talked about his impressions later on, and when he did, it was “with disbelieving horror”.

After the war, Miller worked as a freelance photographer in Florida. His customers included Coca-Cola, Hilton, Ford, Pan American Airways, and National Geographic. He died of Alzheimer’s disease in 1984.

Photographer unknown, 1944

Private collection

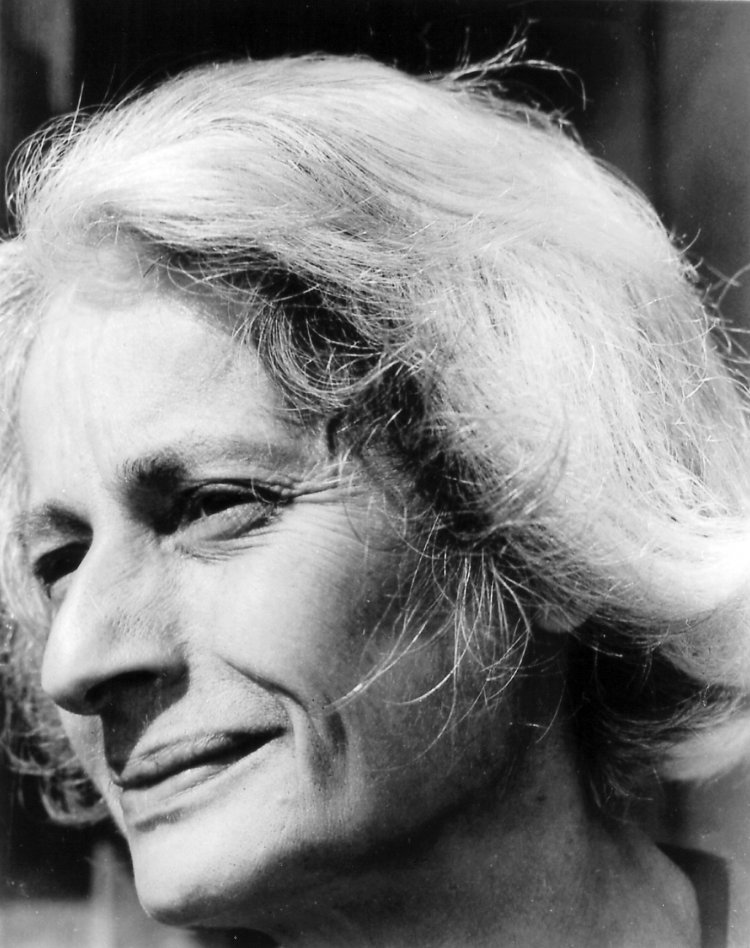

Lee Miller

U.S. war correspondent

23 April 1907 in Poughkeepsie, New York

27 July 1977 in Chiddingly, East Sussex, England

In 1926, Lee Miller began studying art in New York – a shortlived undertaking. Already a year later, her portrait appeared on the cover of the elegant fashion magazine Vogue. She was one of the most sought-after models of the 1920s. In 1929 she visited Paris and ended up staying there as a muse and pupil of the photographer Man Ray. The two developed the solarization technique; she took surrealist photographs and opened her own photo studio.

In 1932 she returned to New York and specialized in portrait photography. She married an Egyptian businessman and member of the jetset, went to Cairo – and found her new life a bore. After three years she returned to the Paris art scene and fell in love with the art historian and later Picasso biographer, Roland Penrose, with whom she went to England when the war broke out.

In the years that followed, as an accredited correspondent of the U.S. Air Corps, Lee Miller introduced war reporting to Vogue. She travelled with General Patton’s Third U.S. Army in the spring of 1945, reaching Buchenwald sometime after 20 April 1945. Her most important report – “Believe it!” – appeared in the June issue of Vogue. Following the liberation of Dachau she triumphantly had herself photographed in Hitler’s bathtub and on Eva Braun’s bed.

After the war, Lee Miller felt compelled to continue reporting about the front. She travelled to Denmark, Hungary, and Romania. Back in England, she married Roland Penrose and tried to get accustomed to bourgeois life. Her country house in East Sussex became a meeting place for the international art scene. She distanced herself from her own artwork, however, and claimed it had all been destroyed. She turned instead to cooking, collected recipes, and participated in cooking contests. In 1977, Lee Miller died of cancer at her country house. It was only after her death that her son, Antony Penrose, rediscovered her work and made it public.

David E. Scherman, April 1945

© Lee Miller Archives, England 2021. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

Louis Nemeth

U.S. Army photographer

10 August 1918 in New York

2 December 2011 in New York

Louis Nemeth came from a Hungarian family of immigrants who settled on 68th Street in Manhattan following their arrival on Ellis Island. A shy boy, he was interested in photography and in the 1930s set up a rudimentary darkroom in the cellar of the building where his family lived. He taught himself the fundamentals of photography by experimenting and consulting books from the library. He later worked for Harold Stein, a studio photographer on 47th Street, for six months, but found conventional “wedding photography” boring. It was then that he decided to become a press photographer.

When he was called up for military service in December 1942, he was initially assigned to office work for an infantry unit. The promotion of the amateur photographer Louis Nemeth to the Signal Corps took place in November 1943 on his own initiative. He then underwent training as a war photographer in the former Paramount Film Studios on Long Island. On 11 February 1945, following an ocean crossing of eight days, he landed on the Scottish coast as reinforcement for the 165th Signal Photographic Company. By way of France and Belgium, he reached the border to the German Reich on 2 March 1945. “This was a bad day for the Germans,” he noted on the back of the photo. During the final days of the war, Nemeth was stationed in Weimar. He had not yet seen the Buchenwald concentration camp, which was only ten kilometres outside town, and had no idea what to expect there. Between April 24 and 26 he photographed foreign delegations on their tours of the liberated camp.

After the war he became a professional press photographer, taking pictures of radio stars for the Mutual Broadcasting System and publishing work as a freelance photographer, for example in the New York Times. Louis Nemeth lived in Manhattan until his death in 2011.

Photographer unknown, 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

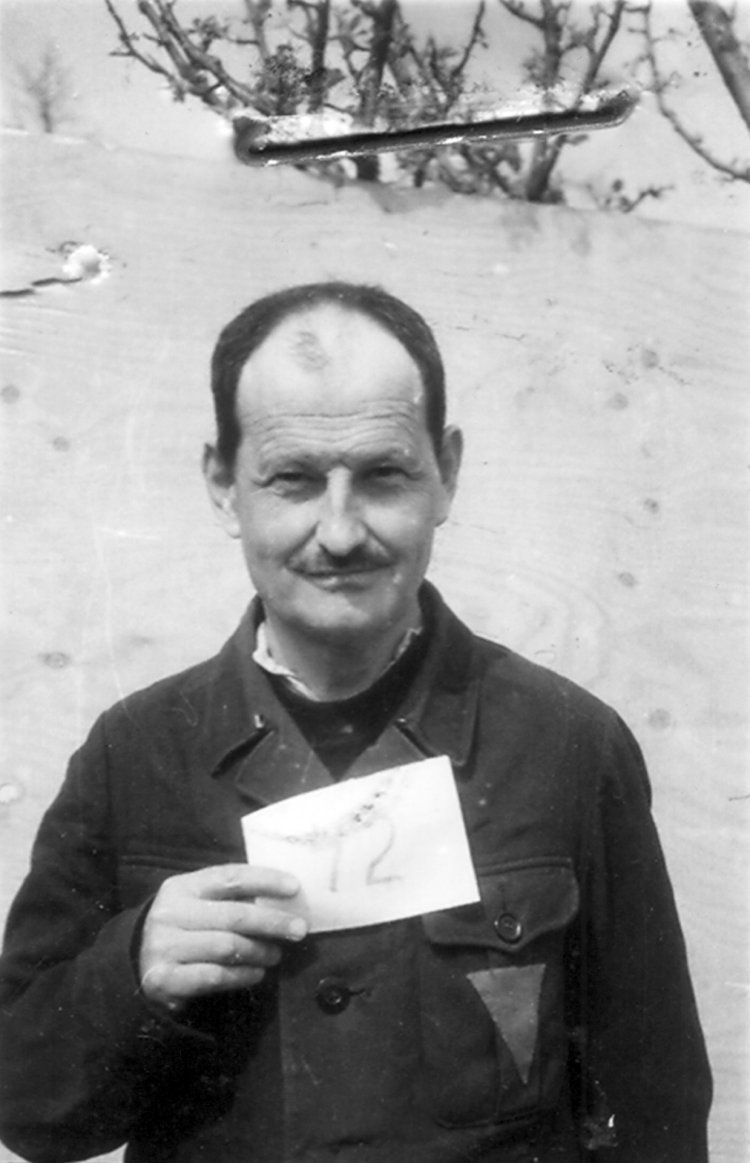

Donald R. Ornitz

U.S. Army photographer

29 February 1920 in New York

14 January 1972 in Los Angeles County, California

Don Ornitz grew up in New York City and Los Angeles, the son of Sadie and Samuel Ornitz. His father was a Jewish social worker and also wrote children’s books, novels, and screenplays. During the persecution of the Communists in the McCarthy era, Samuel Ornitz came to be known as one of the “Hollywood Ten” who were sentenced to prison terms for their “un-American activities” and put on the Hollywood studio blacklists.

Don Ornitz and his brother Arthur already started taking courses in photography at high school. Whereas the latter eventually became a cameraman for film and television, Don Ornitz embarked on a career as a professional photographer. From April 1943 he worked as a military photographer in the 166th Signal Photographic Company of the American army.

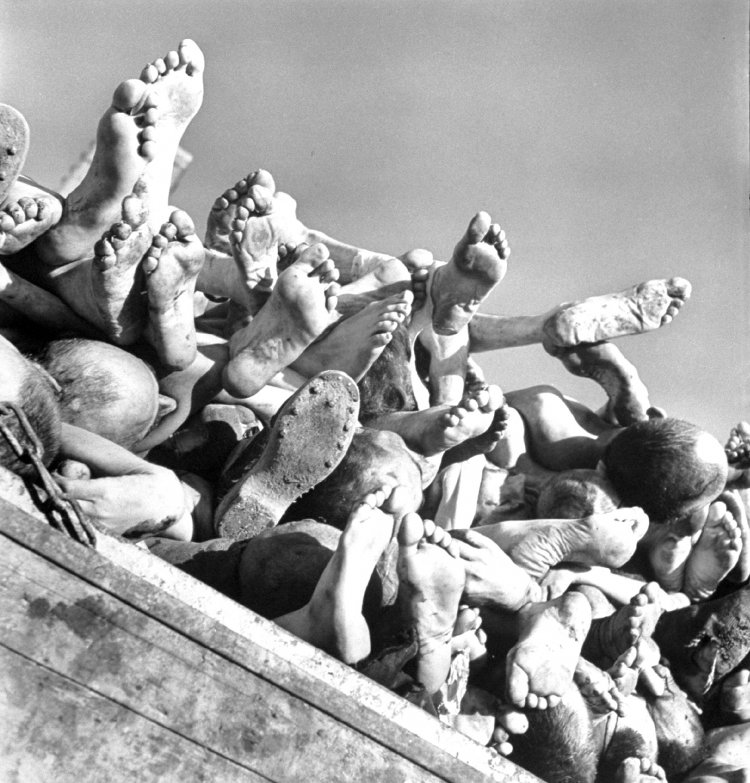

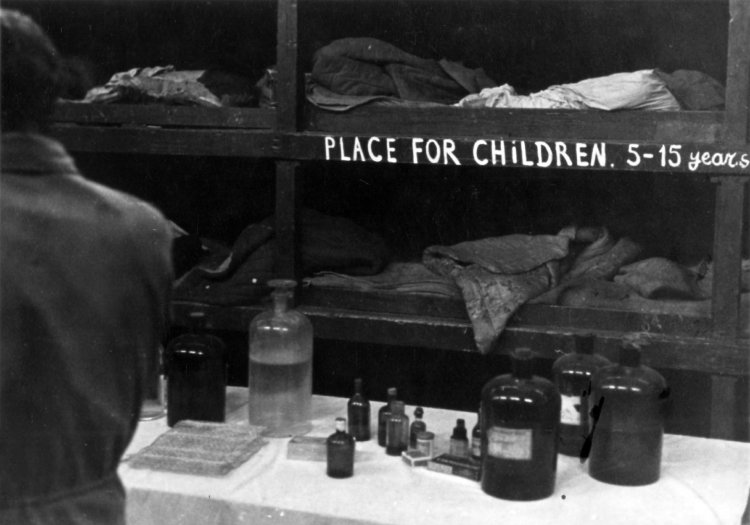

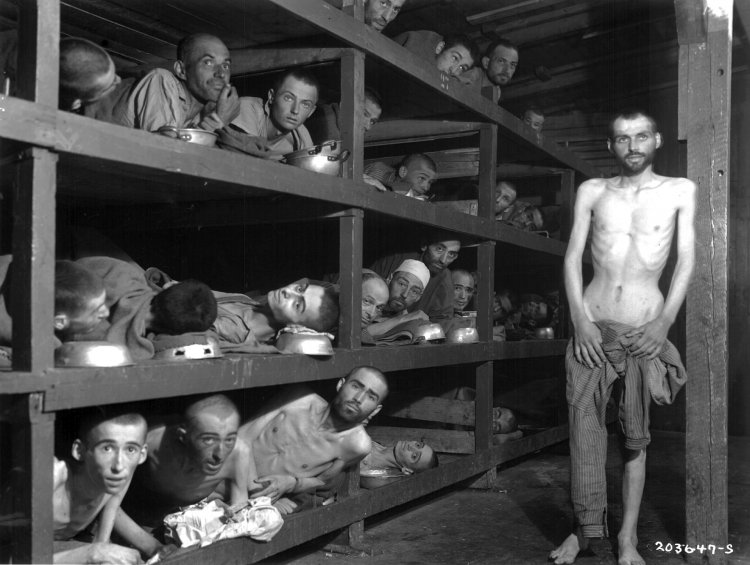

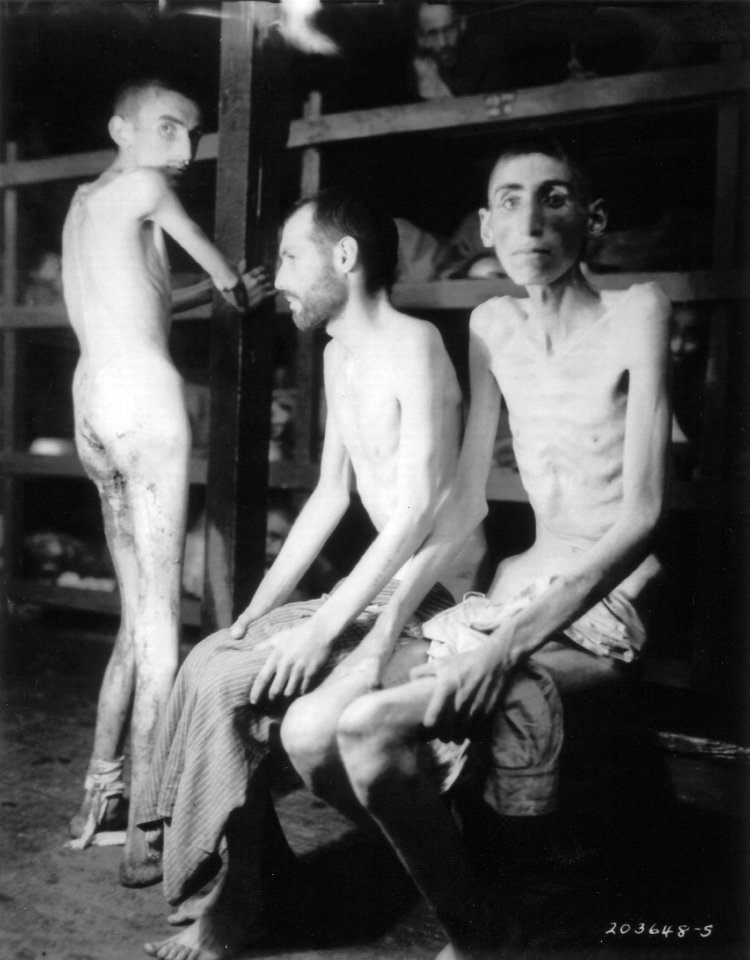

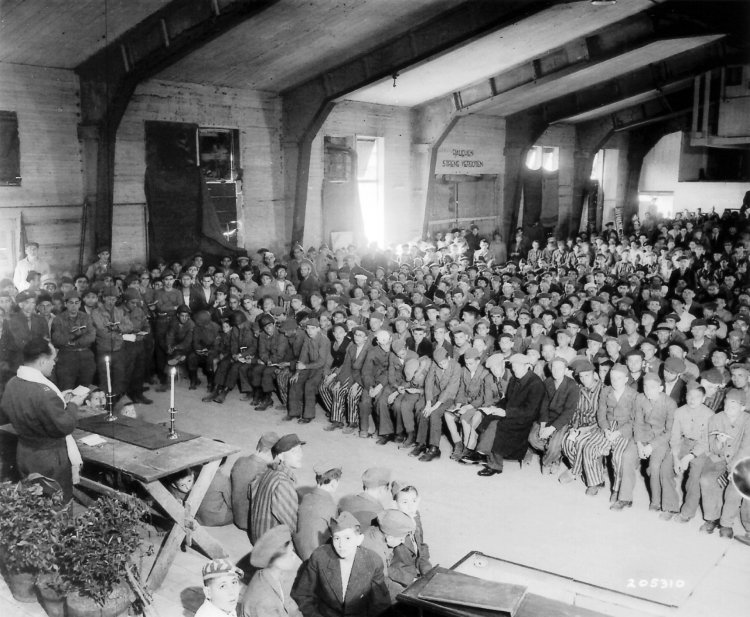

Ornitz’s assignments included the documentation of the war in France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany, the liberation of the Buchenwald and Mauthausen concentration camps, and the discovery of the “Nazi gold” concealed in the Merkers potash mine in Thuringia. Beginning on 19 April 1945, he took pictures in Buchenwald: the funeral service on the muster ground, the inmates’ accommodations in the Little Camp, and the mass graves downhill from the Bismarck Tower.

After the war he returned to Los Angeles where he and his wife Marguerite raised their daughters Laurel and Ellen. Don Ornitz and his wife worked together as free-lance photojournalists for Life and Look. Later he attained success in the areas of fashion and nude photography. He was represented by the Globe Photos agency and published his pictures in Sports Illustrated, Playboy and other magazines.

Photographer unknown, March 1945

Private collection

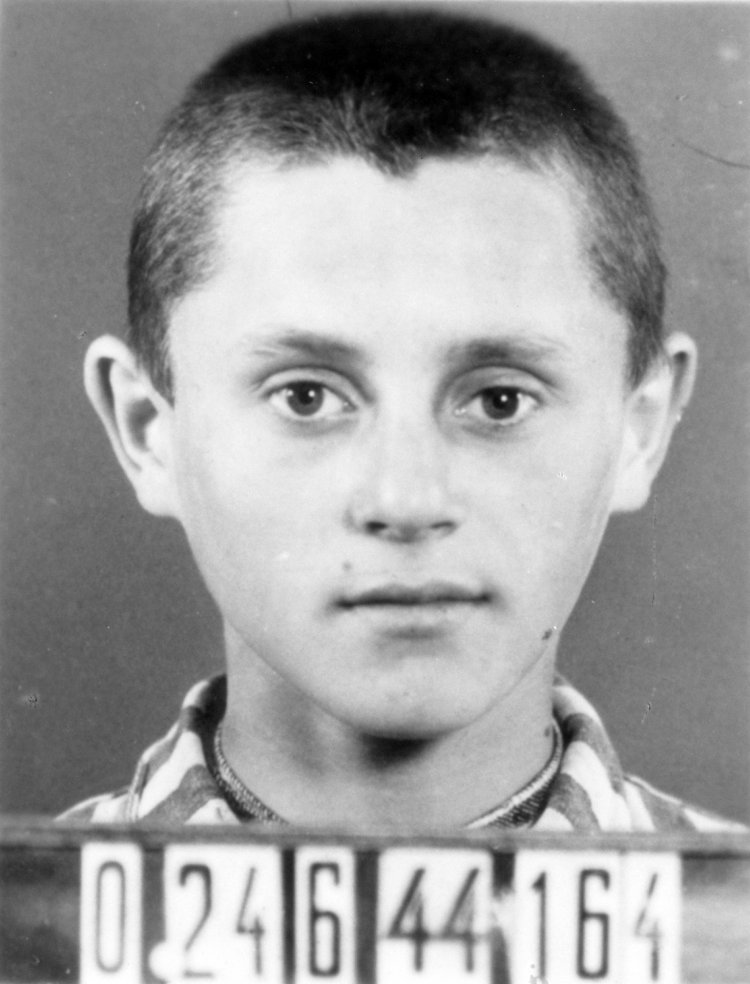

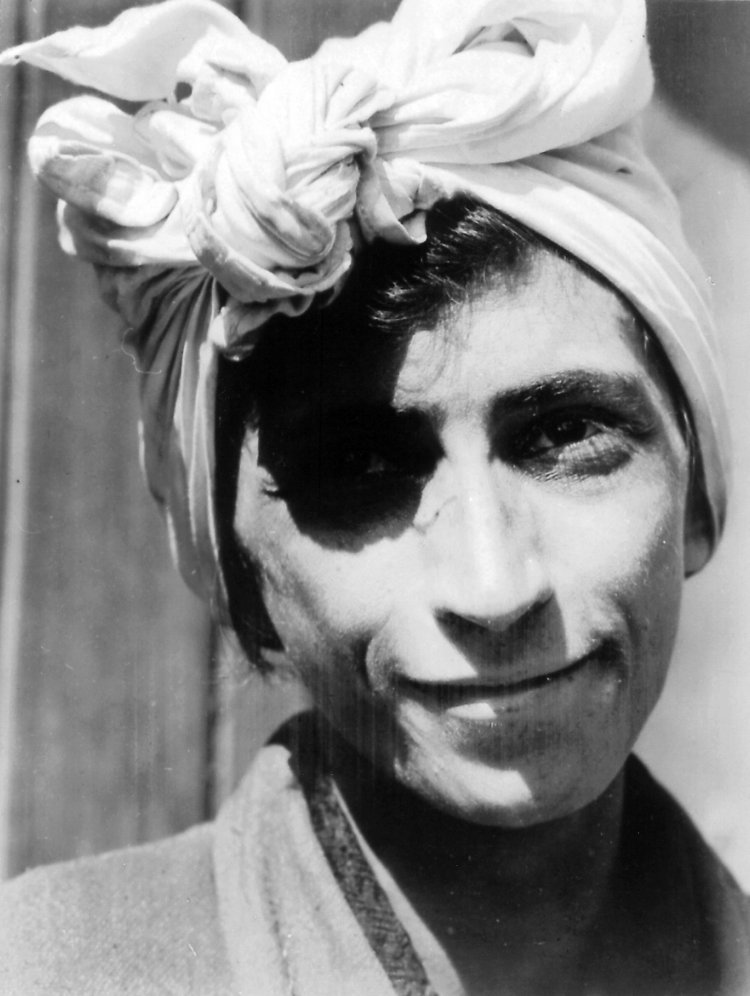

Éric Schwab

French war correspondent

5 September 1910 in Hamburg

1977 in Paris

Employed primarily as a fashion photographer in Paris, Éric Schwab joined the army after the outbreak of World War II. In June 1940 he was taken prisoner of war by the Germans near Dünkirchen but succeeded in escaping six weeks later. During the German occupation he worked in Paris as a photojournalist until the anti-Jewish laws prohibited him from practising his profession.

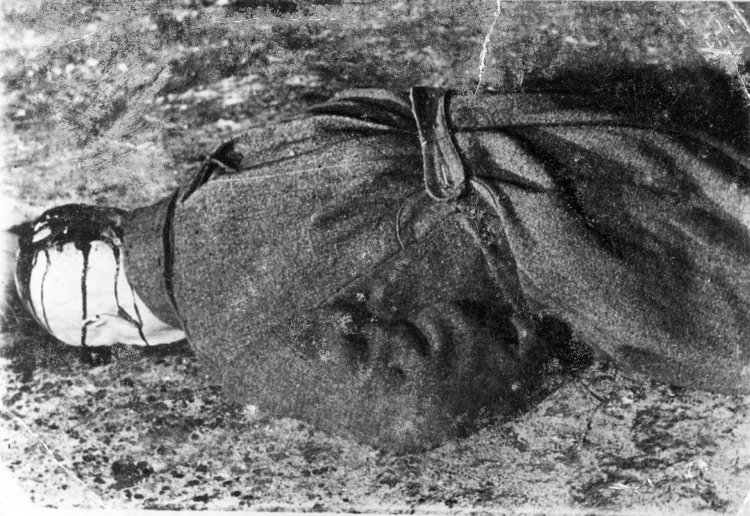

In September 1944, following the liberation of Paris, Éric Schwab went to the front for the Agence France Presse (AFP) news agency and accompanied the U.S. American combat troops on their advance. In addition to documenting the events of war, he was driven by a personal motive – he wanted to find his mother, who had been deported to Terezín. Accredited by the 9th Air Force Corps, Éric Schwab was known for his daredevilry. His companion, the American author and journalist Meyer Levin, compared him to Robert Capa. When the American troops reached the Ohrdruf camp outside Gotha on 5 April 1945 and were directly confronted with the mass crimes committed by the National Socialists for the first time, Éric Schwab and Meyer Levin were present: Their pictures caused a sensation worldwide. The two presumably reached the Buchenwald concentration camp before 16 April 1945. During one “long week”, Éric Schwab restlessly made his rounds in the camp – primarily the Little Camp, where he photographed the survivors and the dead. He focussed on documenting the fate of his countrymen. Éric Schwab and Meyer Levin left Buchenwald sometime after April 22; their further stops included the Thekla subcamp, the Dachau concentration camp, and Terezín, which had been liberated by Soviet troops. There Éric Schwab found his mother.

After 1945, Schwab freelanced for various U.N. organizations, particularly in the developing countries. He worked intermittently for the Magnum Photo Agency. He died in Paris in 1977.

Photographer unknown, ca. 1945

Agence France-Presse, Paris

Alfred Stüber

German inmate (Jehovah’s Witness)

13 February 1904 in Reutlingen

16 January 1981 in Reutlingen

Alfred Stüber was the eldest son of a police inspector in Reutlingen. In 1923 he dropped out of vocational training at the technical school there and began earning his living as a wage knitter. In 1928 he founded a mail-order company for cosmetic and health products; one year later he married. His wife died prematurely of leukemia; Stüber married again in 1931 and became the father of a son. Under the influence of his deeply religious mother, he had already turned to the “International Organization of Serious Bible Researchers” (Jehovah’s Witnesses) as a teenager. In February 1934, the members of this movement were outlawed by the National Socialists in Württemberg. In keeping with his faith, however, Stüber remained active, reproducing illegal treatises in his home.

Alfred Stüber was arrested in October 1937 and committed to the Buchenwald concentration camp on 28 May 1938. The pressure to which the Jehovah’s Witnesses were subjected in the camp was finally alleviated for Stüber by his assignment to the photo department, where other “bible researchers” also worked taking pictures of the inmates for the SS for the purposes of record-keeping.

In April and May 1945 he photographed the liberated Buchenwald camp on behalf of the International Camp Committee. Multiple copies of his photos were made in the camp for the inmates to take back home with them. He also took slides and went on to hold a series of very well-attended slide lectures in the vicinity of Reutlingen. For the introduction to his lecture, he kept a reminder with him, written on a slip of paper: “Do not speak on behalf or in the name of any organization. Only report what I have experienced myself … but only a fraction of it, because what happened in these concentration camps simply evades description!”

In the post-war years, after some initial difficulty, Alfred Stüber finally managed to resume and expand his trade in cosmetic and health articles.

Heinrich Albrecht, April 1945

Private collection

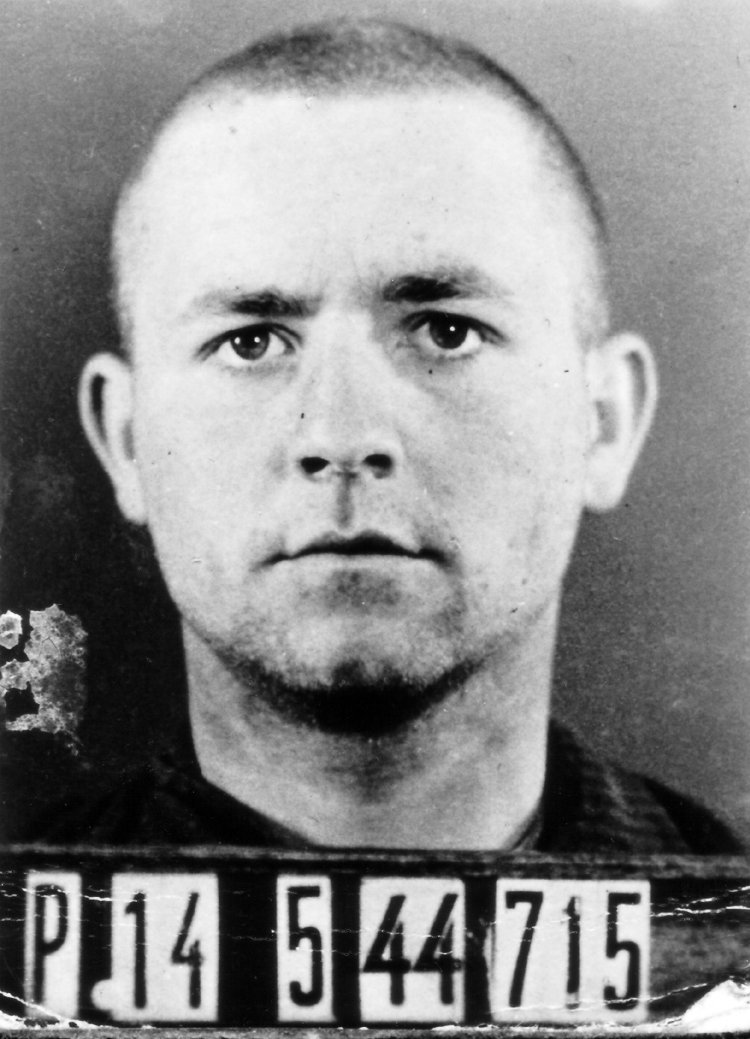

John E. Thierman

U.S. Army photographer

30 October 1907 in Louisville, Kentucky

16 August 1986 in Brownwood, Texas

The son of a railway mechanic, John Edwin Thierman grew up in Kentucky; after high school he worked at, among other places, a historical cemetery. He began taking pictures as a hobby in 1936: his family, natural scenery, and a visit to the 1939 World’s Fair in Chicago.

In mid-1945, having been drafted for military service, he was assigned to the 165th Signal Photographic Company based in Brownwood, Texas. There he met Susan Evelyn McClelland, who would later be his wife; the two became engaged a few hours before his departure. From then on, he wrote to her from the war almost daily.

Five days after D-Day – the American landing in Europe – he arrived at “Omaha Beach”. He was working as a photo lab technician in the mobile darkrooms of the 165th Signal Photographic Company, which was accompanying General Patton’s Third Army. He arrived in Weimar on 28 April 1945. After visiting the liberated Buchenwald camp, he wrote to his fiancée: “Sue, sweetheart: ... the things I saw would turn the stomach of the strongest men who ever lived. Don’t let anyone ever tell you that these things didn’t happen … I love you Sue, with all my heart I love you and I want to get away from all this and back to you and try to forget it. Although I doubt if I will ever forget what I saw today. John”

Soon after his return, the two were married, and in April 1947 Mrs. Thierman gave birth to triplets. Until his retirement, John Edwin Thierman served as an occupational therapist in a clinic for traumatized war veterans in Lexington, Kentucky. Working with his wife, he also turned his passion for photography into a profession; together they published their own articles in various magazines in their home state. Around 1980, after his eyesight had begun to fail, he realized his lifelong dream of becoming a farmer, breeding cattle and growing corn, tobacco, and Christmas trees in the Appalachians. He died on 16 August 1986 at the age of 78.

Photographer unknown, November 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

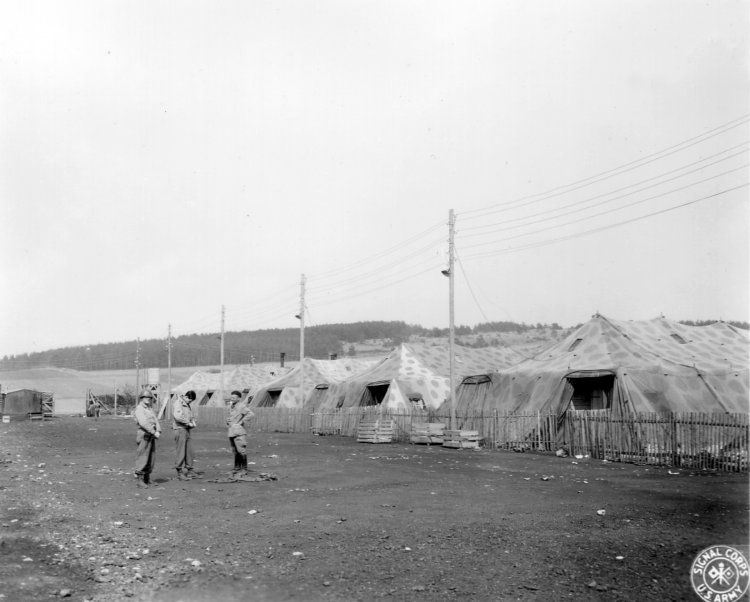

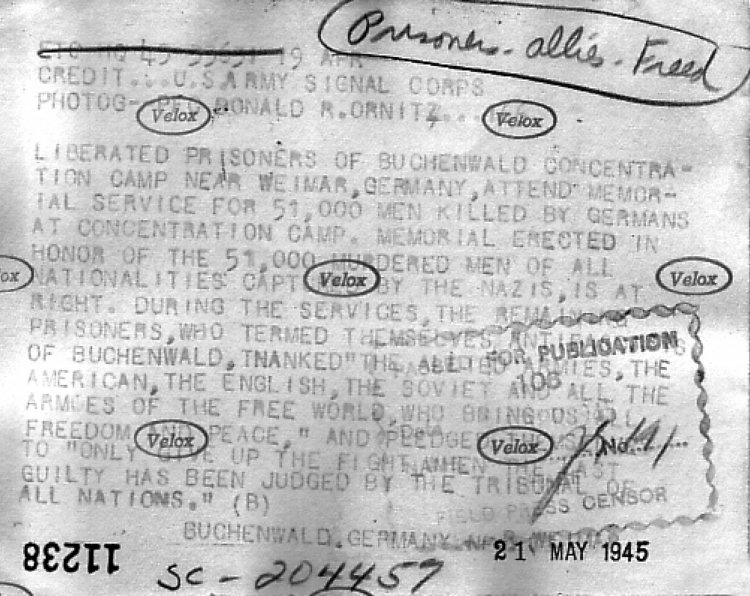

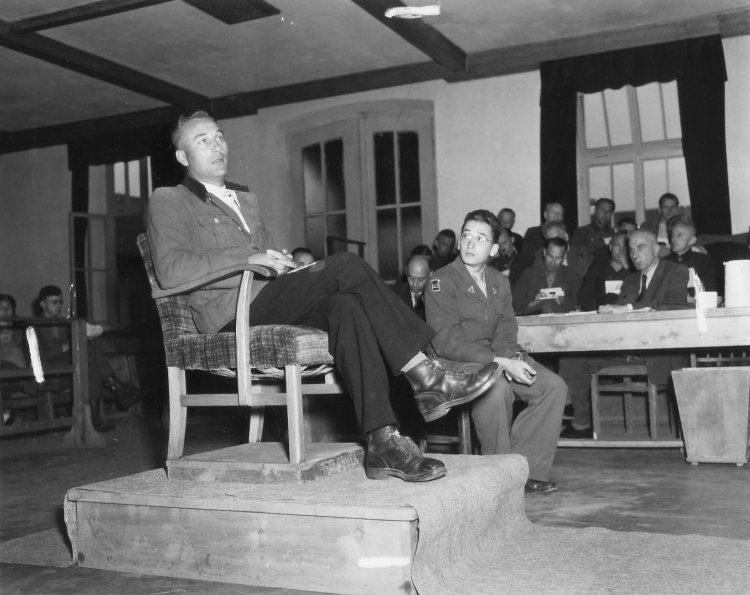

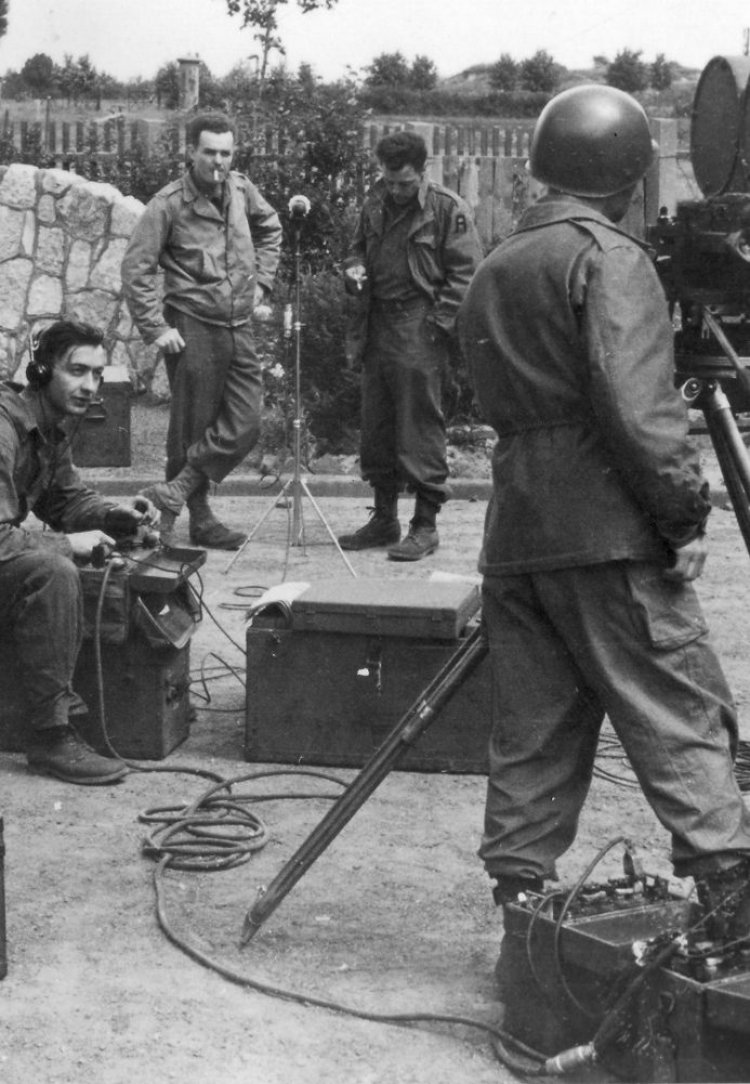

U.S. Signal Corps

“Combat photographers”, we learn in the introduction to Charles E. Sumners’s memories of the 166th Signal Photo Company, are “a rare species of GI” who “carry a camera, not a rifle, into battle”. The 166th Signal Photo Company formed at Camp Crowder in southern Missouri in 1943 was one of the special units of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, assigned with documenting the war in photos and films. In lightweight and almost completely unarmed jeeps, they accompanied General Patton’s Third Army through France, Belgium, and Germany from early August 1944 onwards. True to their epithet “vagabonds”, the army photographers seldom remained in one place for longer than a day. In tiny units frequently consisting of a single jeepload, they travelled from one division to the next. With their “blue passes” they were authorized to go almost anywhere. Their mobile teams documented the advance of Patton’s army, took photographs and shot films during combat operations, and registered graves.

In addition to military activities – traditionally the chief focus of army photographers – they were also instructed to record the horrors of the war and the National Socialist crimes. The Signal Corps accordingly drew up an unparalleled documentation of the Western theatre of war on more than ten million metres of film, of which only a small fraction are known to date.

In April 1945, members of the 166th Signal Photo Company were accompanying the tanks of the Sixth Armored Division when the latter put the the Buchenwald concentration camp SS units to flight. Buchenwald was the first intact and only partially cleared concentration camp to be reached by the Allies. The photos of the 166th Company accordingly took on special significance. Spread to the far reaches of the globe by the press, these images came to serve as evidence of the crimes committed.

The photographers of the 166th Signal Photo Company left the camp in mid-April. They were succeeded by the “combat photographers” of the 165th Signal Photo Company, who made pictorial records of the events taking place in the liberated Buchenwald concentration camp until the early summer of 1945.

John E. Thierman, U.S. Signal Corps, October 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Willy van Heekern

German professional photographer

14 March 1898 in Kevelaer am Niederrhein

17 May 1989 in Essen

Willy van Heekern learned photography and darkroom work in the studio of his father, the painting conservator Arnold van Heekern. The first photos he published were of the Kapp coup; they were exhibited in a stationery shop. In 1923, after completion of studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) in Essen, he worked as a photographer and decoration painter in Düsseldorf; in 1925 he became a freelance photographer. In 1930 he married Ellinore Mathia and became the father of a daughter. Van Heekern worked with a focal-plane shutter camera made by Contessa-Nettel, an Ermanox, and various travel cameras, and was also already experimenting with a 35mm Leica.

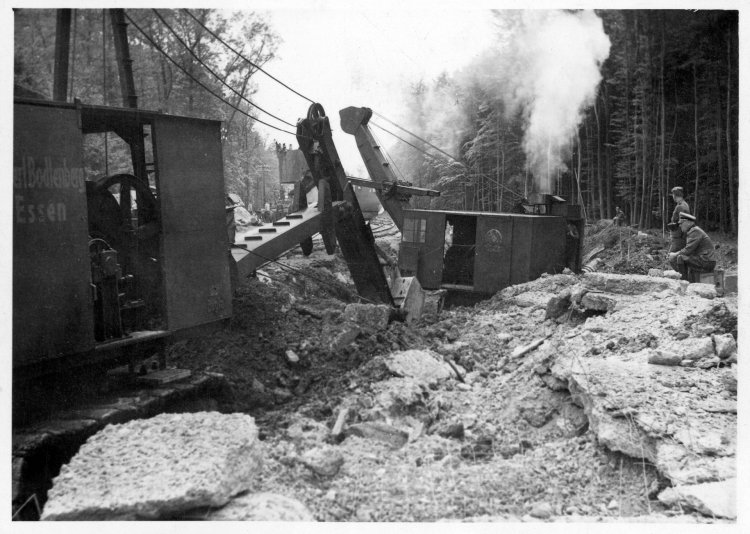

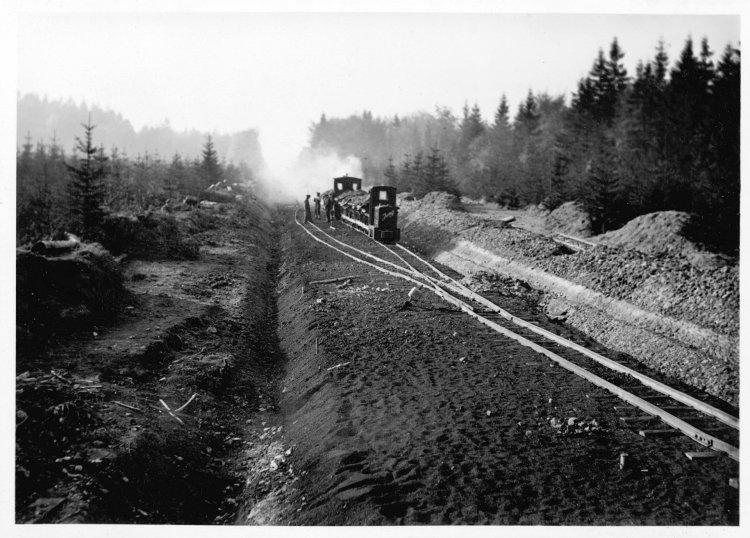

Beginning in 1936 he had an exclusive contract with the Chamier publishing company of Essen. He photographed the Olympic Games in Berlin and a joint appearance of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in 1938. After the newspaper was closed in 1941, he supplied the illustrated magazine Die Wochenschau with photo stories, for example on the National Socialist “Volkswohlfahrt” (people’s welfare) and “Kinderlandverschickung” (programme for sending children to camps in the countryside). His professional activities protected him from conscription to the Wehrmacht. From 1943 onwards he documented the air attacks on Essen, war destruction, and the clearing of rubble by Buchenwald concentration camp inmates in Duisburg.

In the post-war period, Willy van Heekern continued two projects already begun during the war: a documentation of architectural monuments in the Rhineland on behalf of the Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments, and one of the reconstruction of Essen. After 1946 he worked as a freelance press photographer for the Rheinische Post and the Neue Ruhr Zeitung. He retired in 1970. His pictorial archive (120,000 negatives, 6,000 positives) has been in the photo archive of the Stiftung Ruhr Museum in Essen since 1984. Willy van Heekern died in Essen in 1989.

Self-portrait, 1930s

Fotoarchiv Stiftung Ruhr Museum, Essen