The View from the Outside

Jean Améry

On Public Display

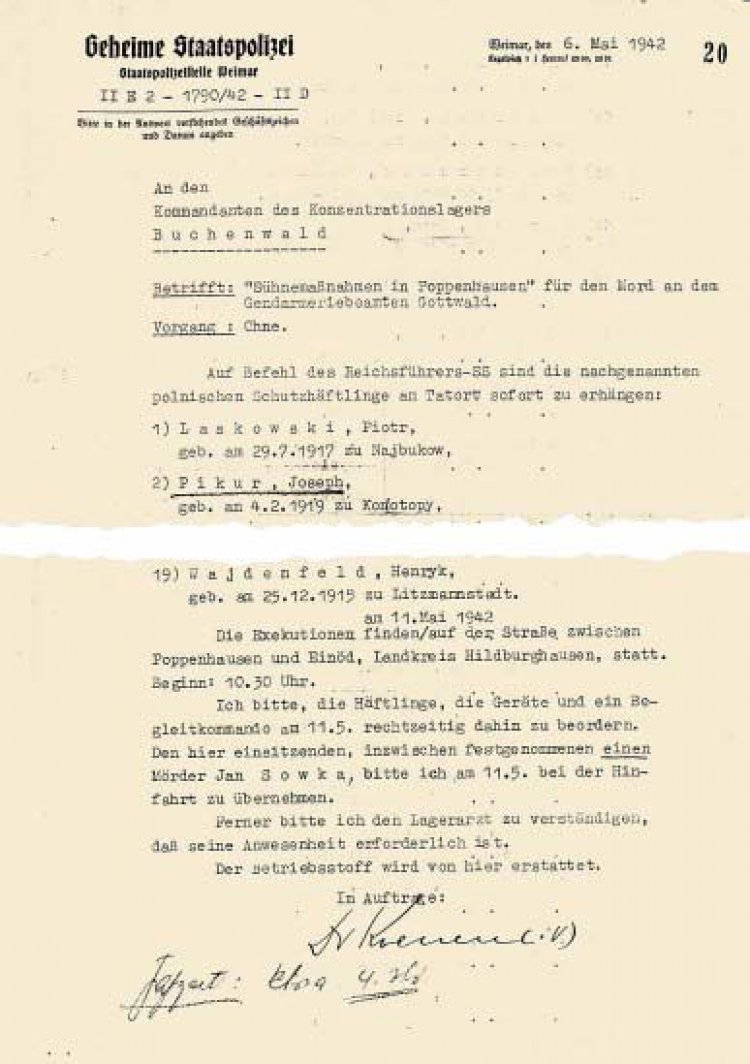

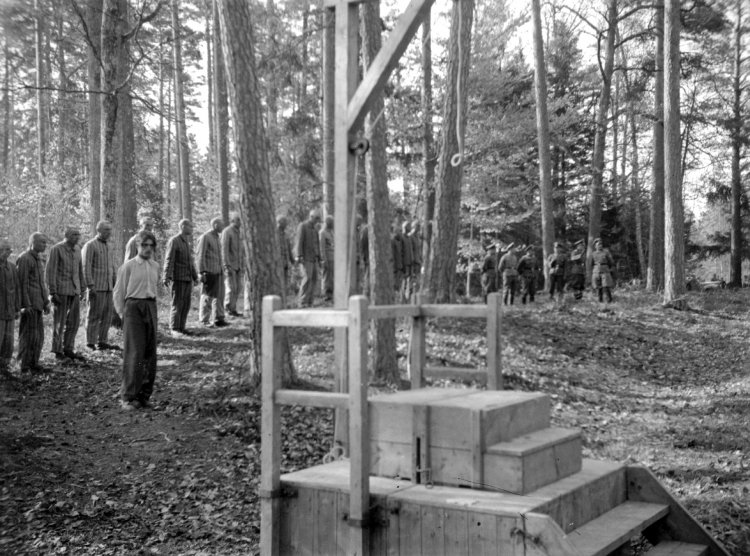

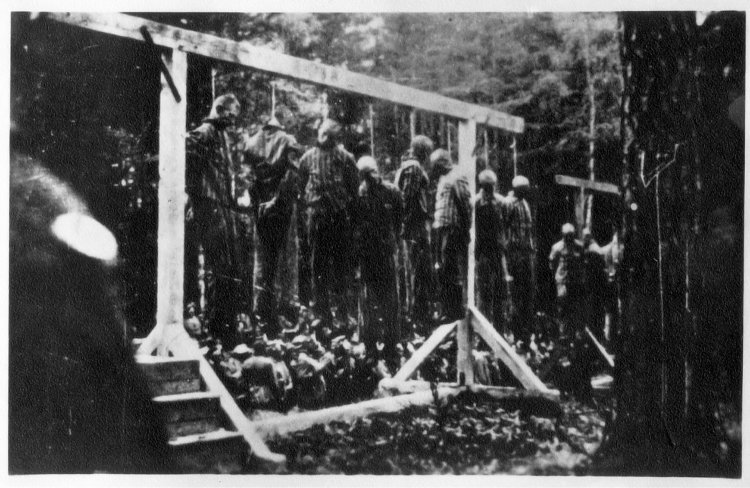

The Buchenwald SS carried out executions outside the camp as well. These events were public. Even their photographic documentation was permitted.

When the war began, forced labourers and prisoners of war arrived in a society which had already been undergoing a process of formation as a racial and war community for many years, due not least of all to the threat of the concentration camps. In order to emphasize the strict isolation of these persons from German society, the Nazi party availed itself of rituals of public exhibition reminiscent of medieval practices. Beginning in the spring of 1940, German women who had had illicit contact to Polish forced labourers were led to the marketplaces of towns, where their heads were shaved as a means of humiliating them before the public. Photos of these events were frequently published in the local press. Following this “exclusion ritual”, the women were often incarcerated. The Polish men involved in these cases were committed to the nearest concentration camp.

In the years 1940 to 1942, the Gestapo repeatedly came to fetch Polish men from Buchenwald in order to hang them publicly on the gallows in various towns in Thuringia. The Polish forced labourers from the surrounding towns and villages were compelled to participate in these state-sanctioned murders and the residents were invited to come and watch. It is likely that both the Gestapo and the local population took photographs of these public acts of murder. Nevertheless, only a few such pictures have survived.

What is probably the largest group of photos, presumably taken by both private spectators and members of the Gestapo, shows the murder of one Polish forced labourer and nineteen Polish Buchenwald inmates in the vicinity of Poppenhausen on 11 May 1942. In their entirety, these pictures not only convey an impression of the event itself, but also bear witness to how public participation in the execution of “strangers to the community” became standard behaviour during the first few years of the war.

Weimar Secret State Police (Gestapo), 6 May 1942

Landesarchiv Thüringen – Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 11 May 1942

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Photographer unknown, 11 May 1942

Landesarchiv Thüringen – Staatsarchiv Meiningen

Photographer unknown, 11 May 1942

Landesarchiv Thüringen – Staatsarchiv Meiningen

Photographer unknown, 11 May 1942

Landesarchiv Thüringen – Staatsarchiv Meiningen

Photographer unknown, 11 May 1942

Landesarchiv Thüringen – Staatsarchiv Meiningen

The Clandestine Photo

In the public perception, concentration camp inmates had the status of outcasts. They were not photographed, but at most merely abused or spat on.

Buchenwald was designed as a closed camp. During the first few years of its existence, the majority of the inmates were strictly isolated from society and the SS endeavoured to prevent encounters with the local population. The inmate labour detachments marched out to their workplaces – frequently located in the direct vicinity of the camp – in the early morning hours and returned in the evening. Thus, initially, only the residents of the communities to the south and north of Ettersberg Mountain actually saw the work gangs of men dressed in inmates’ drill and assigned to labour in the construction of the Berlstedt clinker works (1938/39) and the Tonndorf-Daasdorf-Buchenwald water conduit (1938/40).

The only photograph of an inmate work gang originating during this period was taken clandestinely from the attic window of a house in Gaberndorf. It shows the waterworks detachment on the road to Daasdorf. A seventeen-year-old boy by the name of Armin Meisel took it with the Voigtländer bellows camera he had received for his birthday. He waited for fair weather and took a single hasty photo. Although he thought “this could someday become something historical”, he did not show it to anyone for fifty years.

On the one hand it clearly testifies to the fact that not all doors and windows remained closed when inmates passed through the village. The manner in which it was taken, however, is also indicative of the fear associated with photographing a scene of this kind. It was presumably not only fear of punishment, because we do not know of a single case in which a person was prosecuted for photographing inmates outside the camp. Rather, in National Socialist society, looking the other way was the norm, and deliberate observation – to say nothing of taking pictures – was unthinkable. Nevertheless, there was another form of spectatorship that came to symbolize open acknowledgement of Nazi ideology. It was not unusual for newly arriving inmates to be verbally abused or spat on by townsfolk as they marched from Weimar Main Station to Buchenwald. No photographs were taken of these occurrences.

Armin Meisel, resident, summer of 1939

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Armin Meisel, resident, summer 1939

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

“... in the midst of the German people”

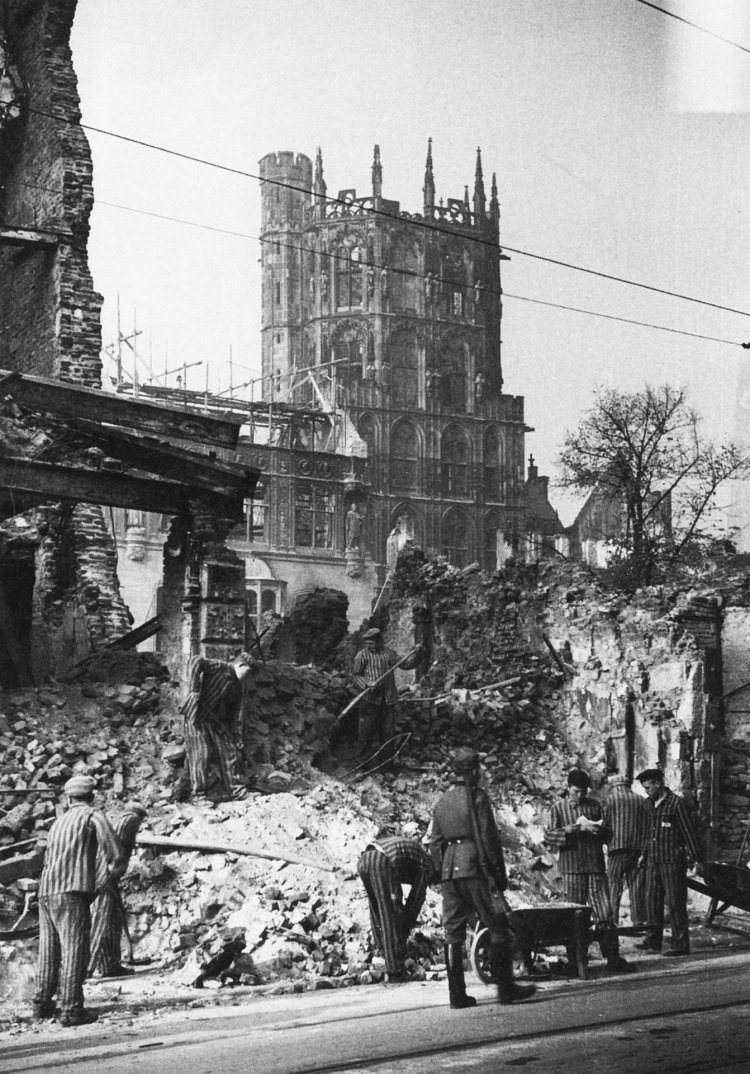

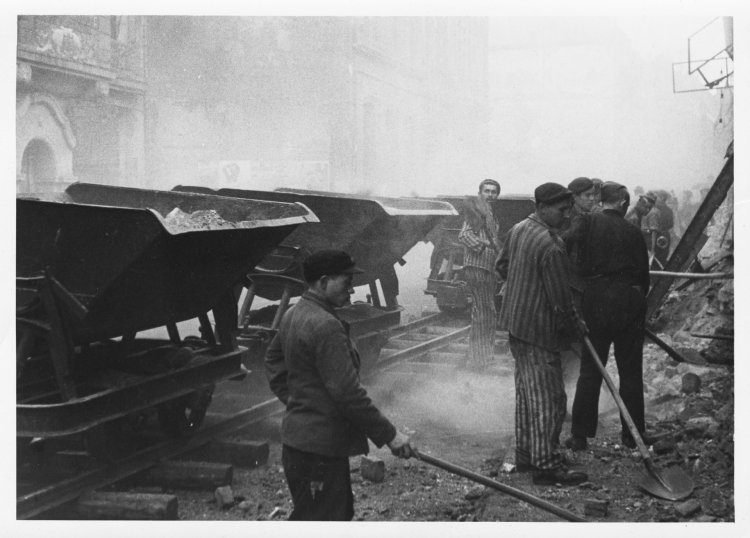

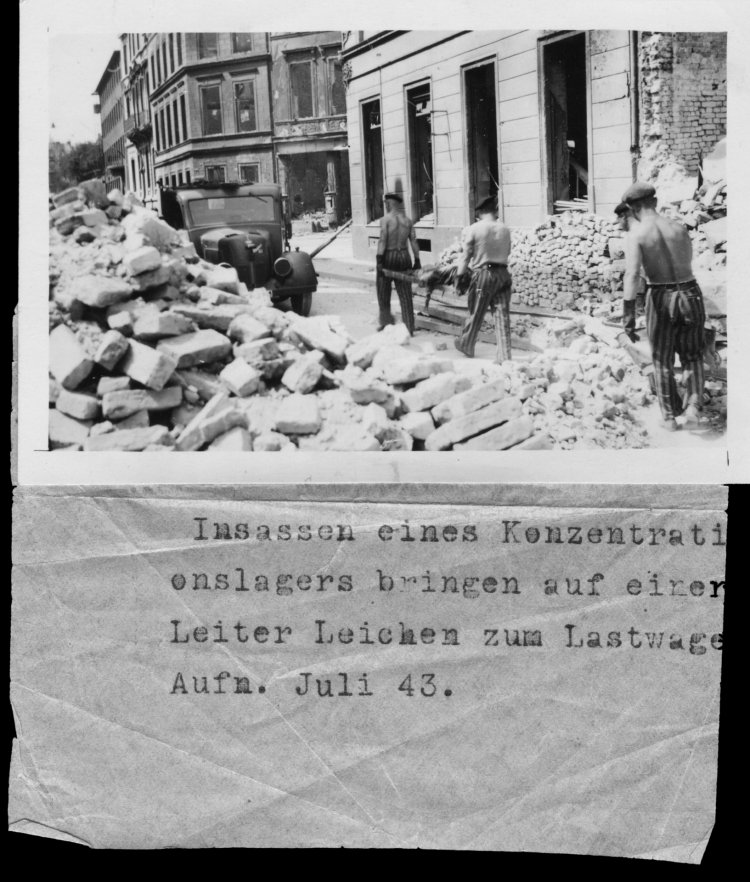

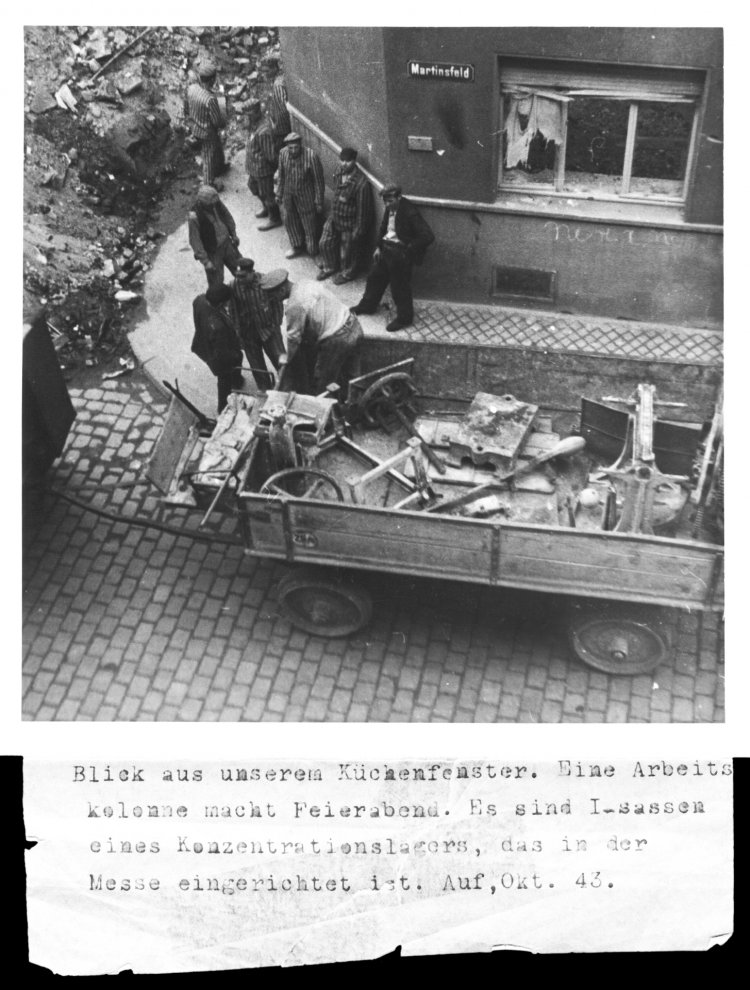

Through the establishment of the subcamp system, inmates became an increasingly visible element in everyday wartime society. Photographs were taken particularly of their presence in the streets of the towns where they were put to work clearing rubble and blind shells.

The bombardment of the Ruhr region and towns in the Rhineland beginning in the fall of 1942 severely unsettled the German public. In this situation, the rapid clearance of streets blocked by rubble, the retrieval of the dead and the swift removal of blind shells served as demonstrations of local Nazi administrations’ ability to take action. For the extremely dangerous rubble-clearing work, the SS set up mobile inmate construction brigades in various concentration camps. Their deployment and establishment – for example at the Cologne fairgrounds camp – not only marks the beginning of a new development in the concentration camp system, but also represents the arrival of inmates as a visible element in everyday Nazi wartime society.

Soon more than half of the Buchenwald inmates were no longer in the parent camp but on the streets of the towns and in factories – in the midst of the German population – on a daily basis. Yet their presence is not documented photographically everywhere. Professional and amateur photographers pointed their lenses at the inmates in the rubble fields only now and then. As a result, there are a few series of photos taken in the streets of Cologne and Weimar showing inmates at work under the supervision of armed guards. The photos portraying bomb clearance detachments are much different in character. Hundreds of inmates met their deaths performing this work. Although the origination and provenance of these photographs remain shrouded in mystery, they can be viewed as what may well be final testimonies to the lives of the persons they portray. At the same time, they document a relationship between the inmates and the guards forged by the fact that the lives of both were equally dependent on luck. In any case, this small number of photos does not represent the perception of concentration camp inmates prevalent among the majority of the German population.

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Willy van Heekern, German professional photographer, 1943

Fotoarchiv Stiftung Ruhr Museum, Essen

Willy van Heekern, German professional photographer, 1943

Fotoarchiv Stiftung Ruhr Museum, Essen

Photographer unknown, July 1943

Historisches Archiv Stadt Köln

Peter Fischer, 23 October 1943

Historisches Archiv Stadt Köln

Peter Fischer, 23 October 1943

Historisches Archiv Stadt Köln

Julius Radermacher, late 1943

NS-Dokumentationszentrum Köln

Julius Radermacher, February 1943

NS-Dokumentationszentrum Köln

Julius Radermacher, late 1943

NS-Dokumentationszentrum Köln

Photographer unknown, 25 November 1943

Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Köln

Josef Fischer, July 1943

NS-Dokumentationszentrum Köln

Josef Fischer, October 1943

NS-Dokumentationszentrum Köln

Photographer unknown, 1943/44

Norbert Krüger collection, Essen

Photographer unknown, 1943/44

Norbert Krüger collection, Essen

Photographer unknown, June 1943

Stadtarchiv Bochum

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar

Günther Beyer, German professional photographer, February 1945

Constantin Beyer, photographer, Weimar