The Inmates

Rolf Kralovitz

The Inmates in the Eyes of the SS

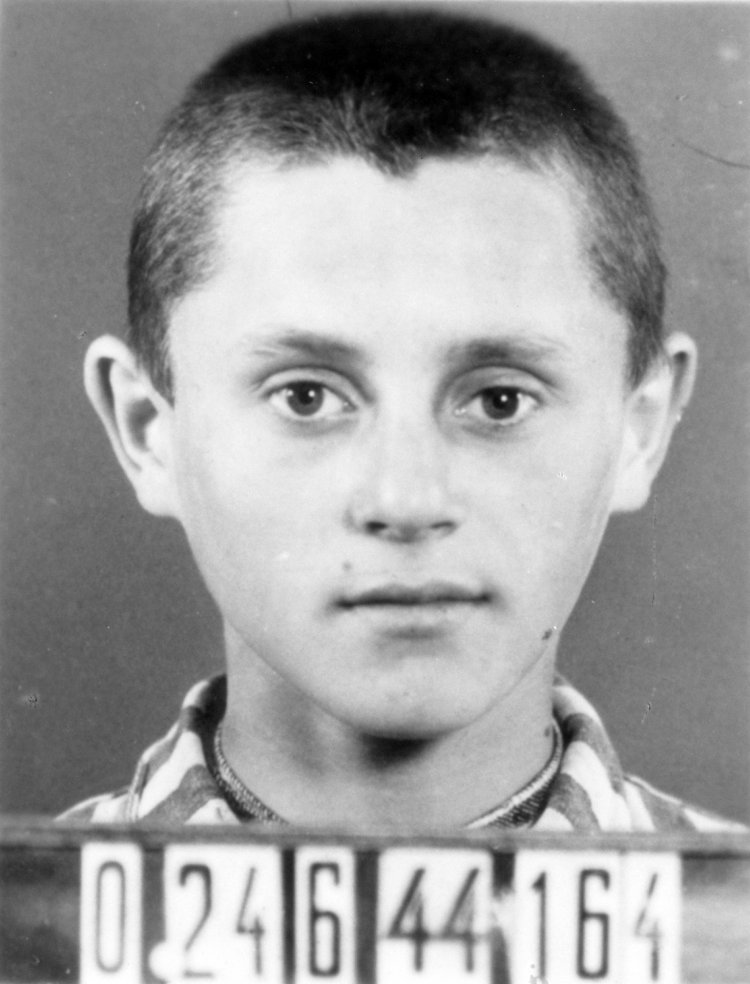

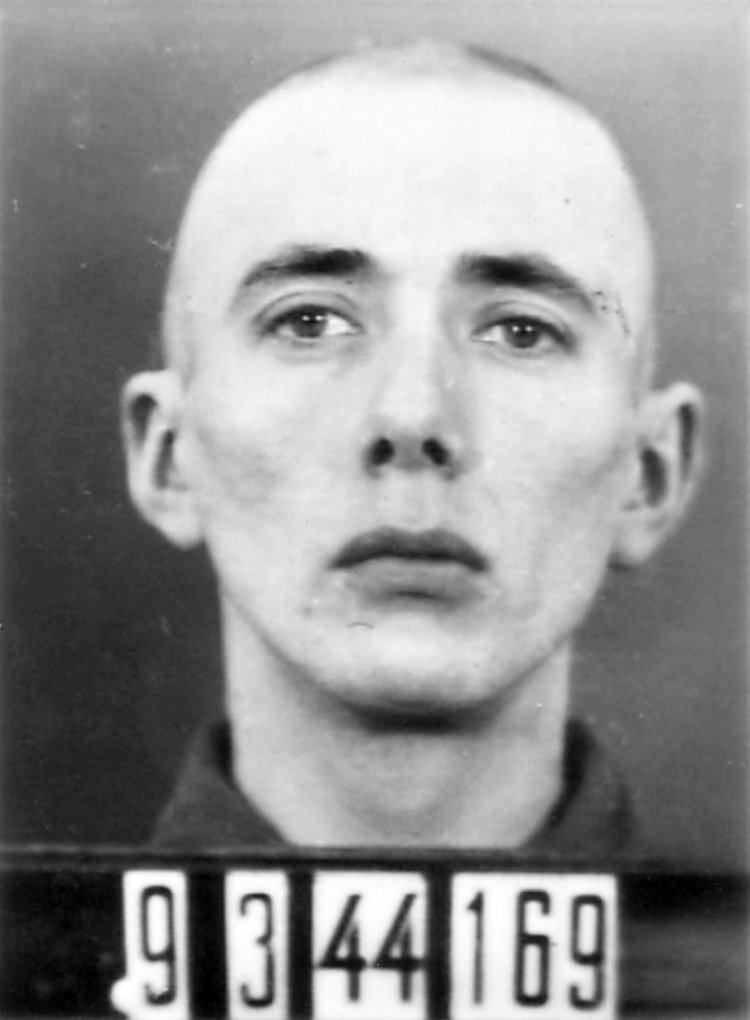

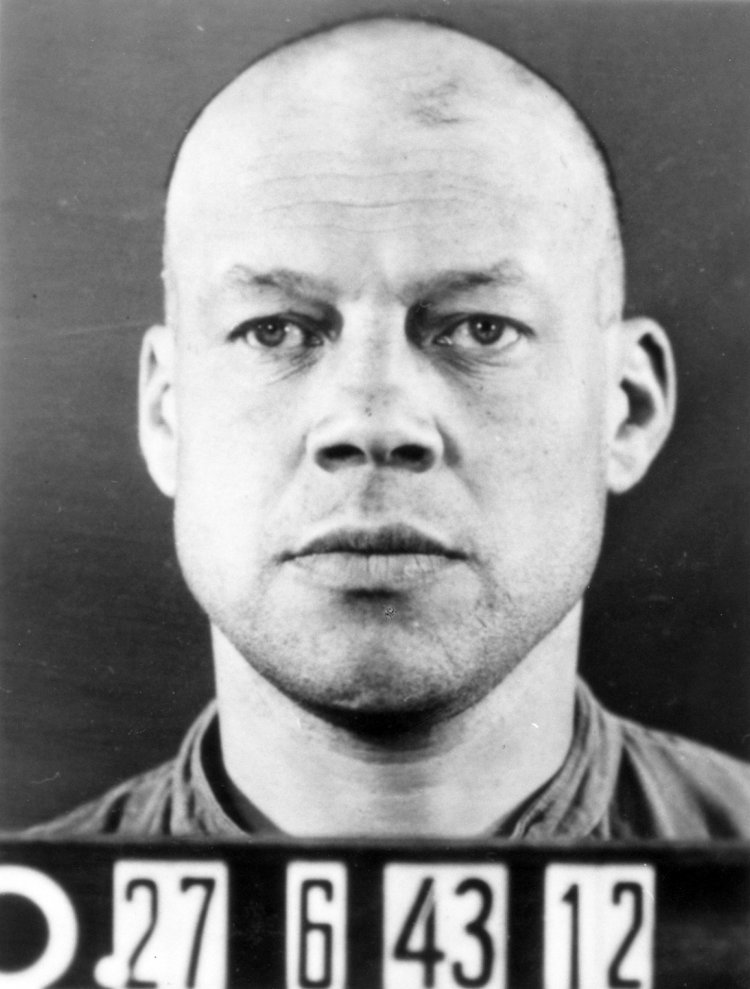

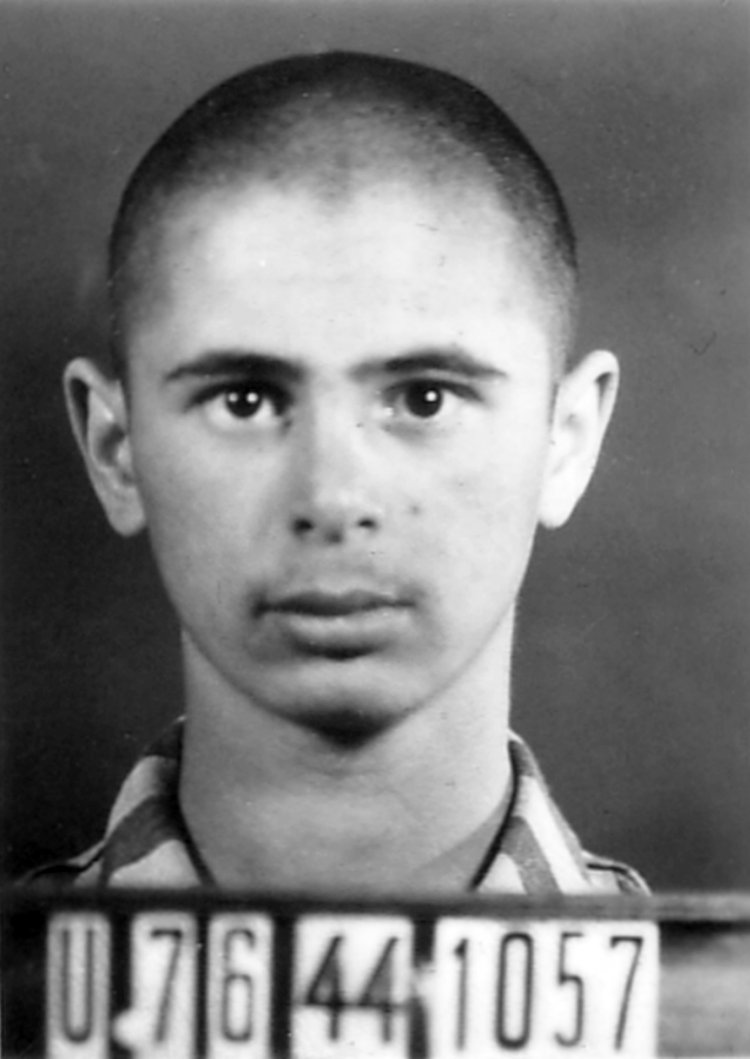

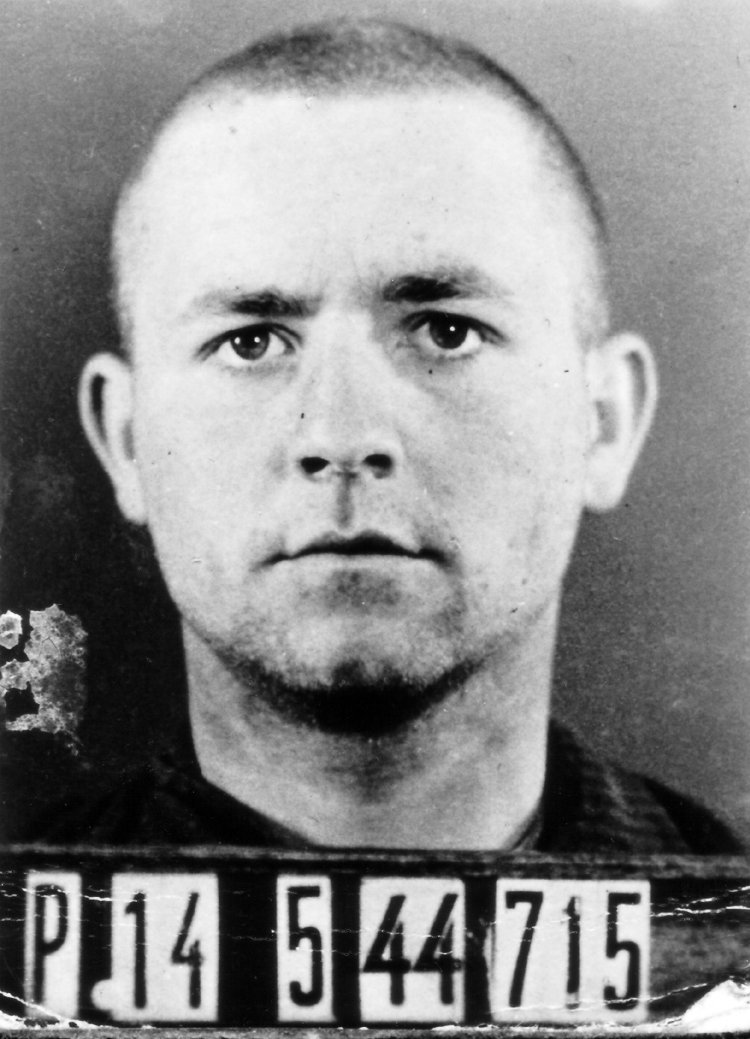

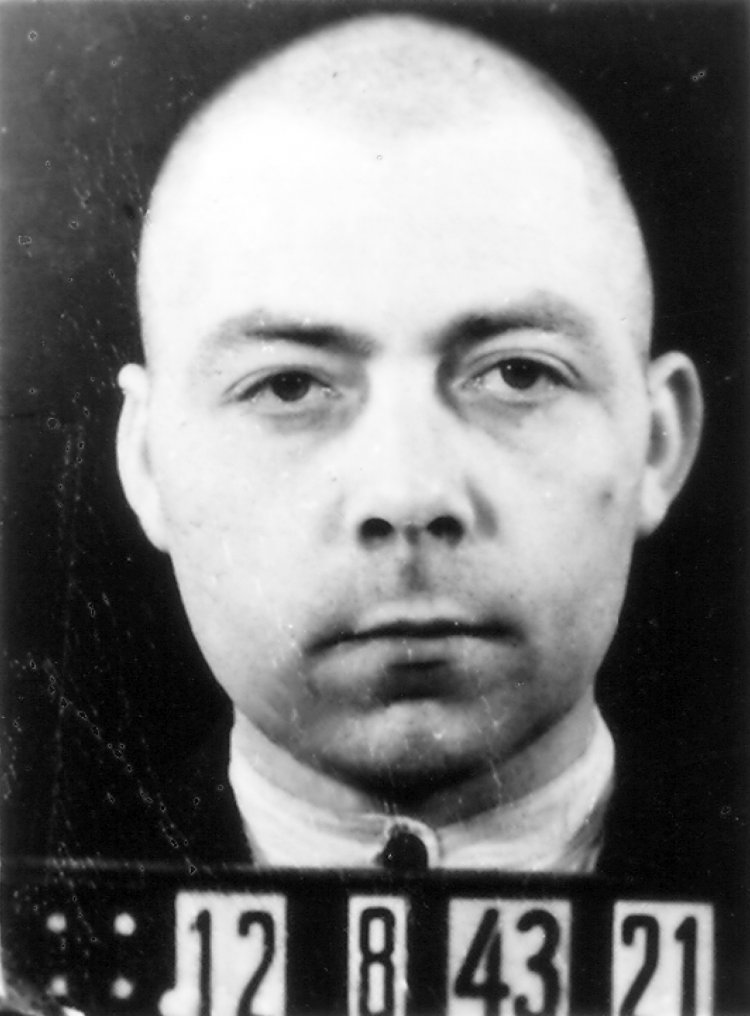

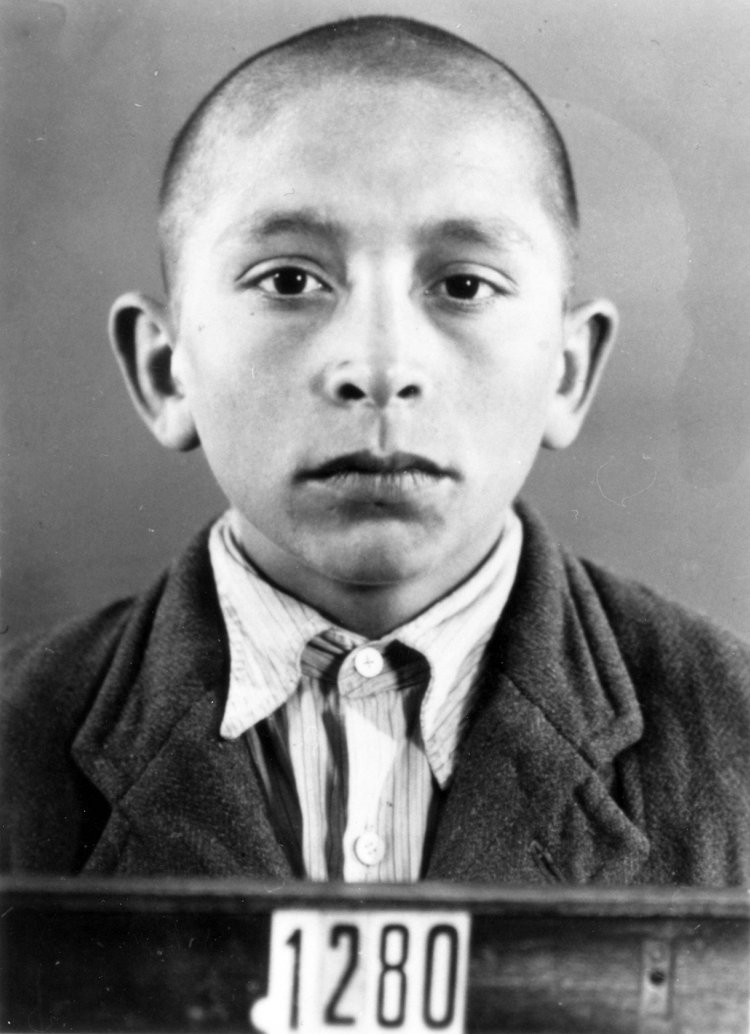

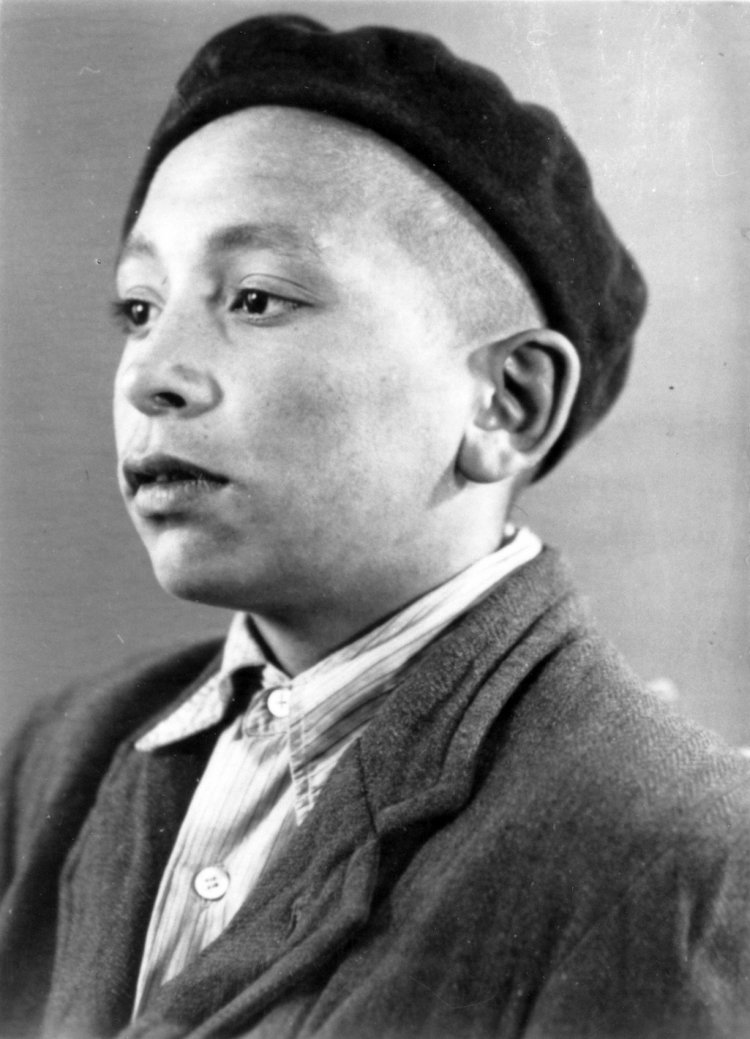

The camp command had persons who had been committed to Buchenwald from all over Europe photographed for its files. Photos of selected inmates were also used as confirmations of the Nazis’ racist ideology. Some visual documents of the camp horrors have come down to us because inmates working in the photo department managed to hide a number of pictures.

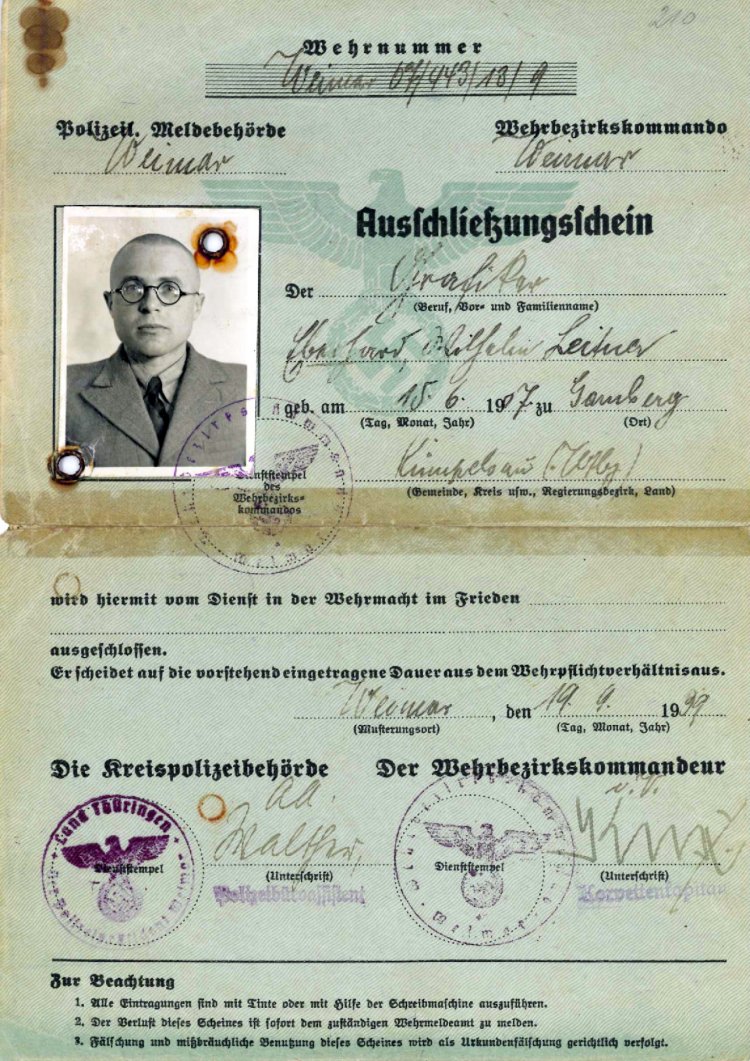

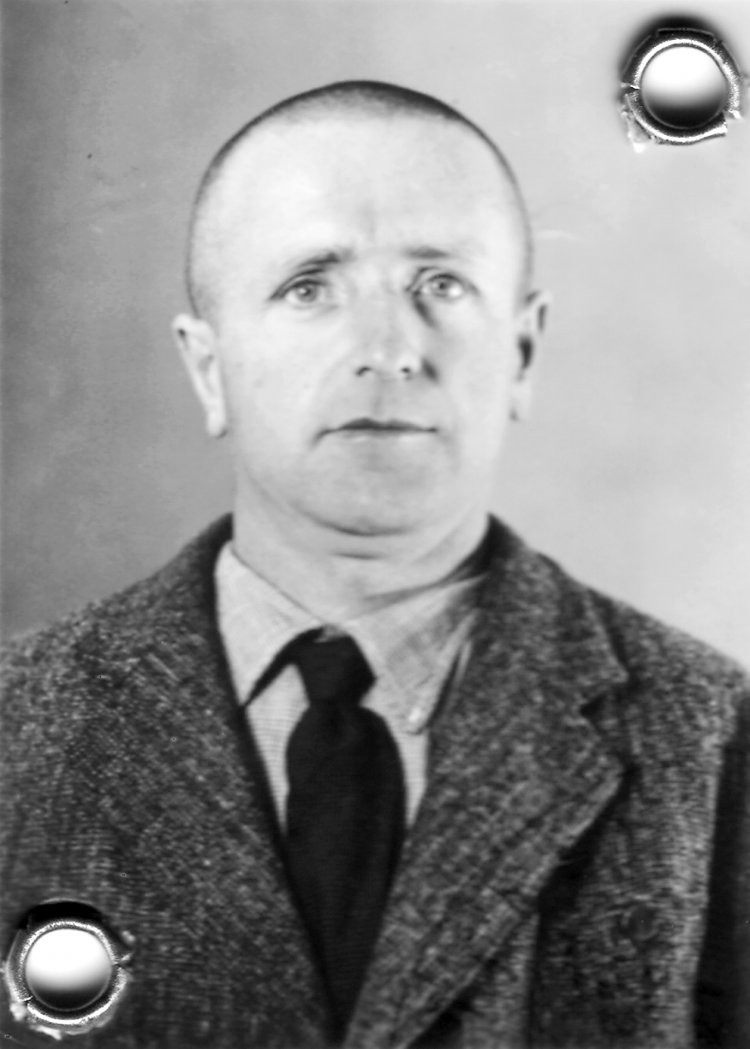

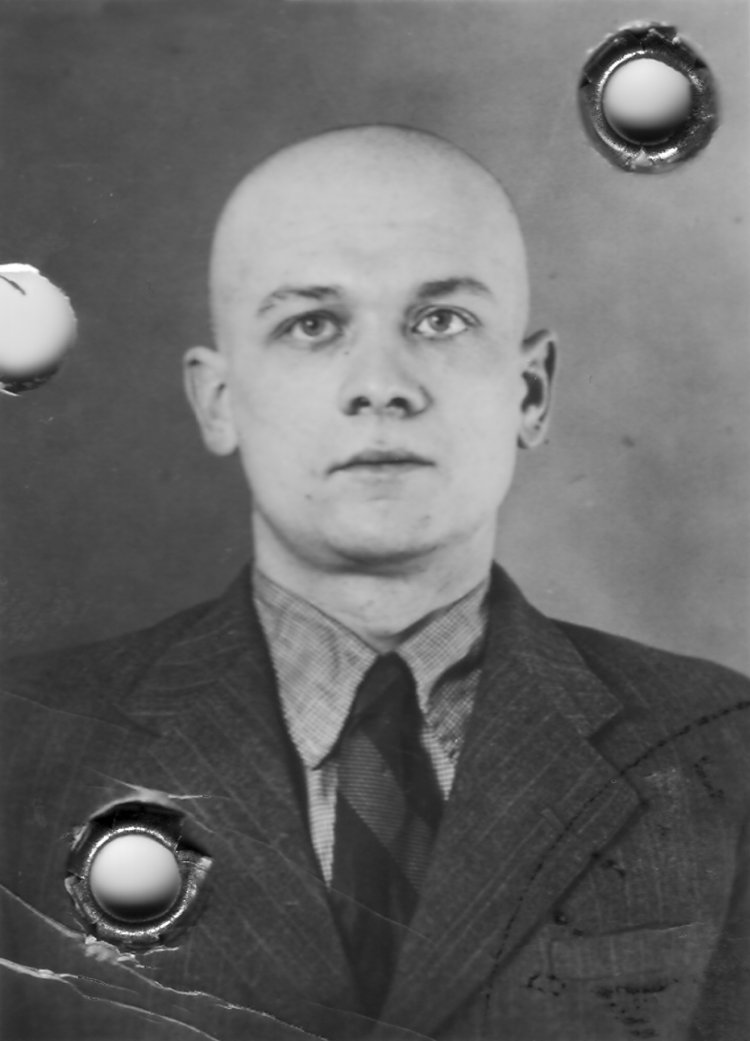

From 1939 onwards, inmates were photographed for the camp card file shortly after their arrival. In the manner practised by the police, triple portraits were taken, showing the inmates with shaven heads and wearing inmate uniforms. Rather than the name tag commonly used in the criminal context, the date of committal and the transport number served the purposes of identification. Passport photos of Germans classified as “unworthy to bear arms” – showing the political inmates in clothing kept on hand specifically for this purpose – were made for the “army exclusion certificates” appended to the inmate records.

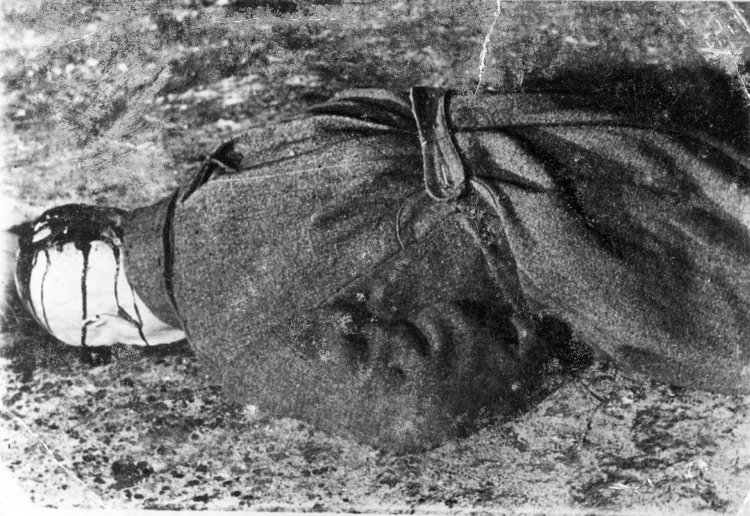

The pictures were taken by the photo department, which was located in the barrack of the so-called political department, the branch office of the Secret State Police (Gestapo) in the camp. Under SS supervision, an average of nine inmates worked in the photo department, primarily Germans imprisoned for political reasons or as Jehovah’s Witnesses. They were also responsible for documenting deaths. This category comprised suicides, hangings, and persons determined dead on arrival. Edo Leitner – the department kapo for many years – and a number of his comrades made secret copies of such photos and hid them in tin containers which they buried beneath the barrack. When the entire photo inventory was destroyed during the air raid in 1944, the concealed photos were among them. Only Georges Angéli succeeded in saving a few photos of murdered inmates.

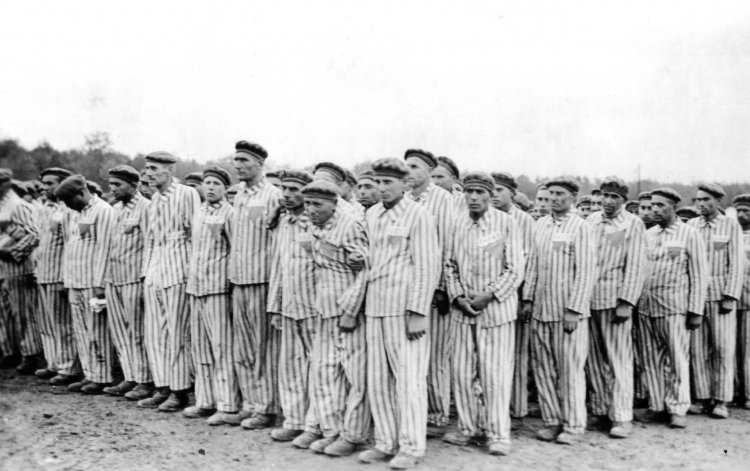

The SS were furthermore interested in the inmates as motifs when there were out-of-the-ordinary events to be documented, such as the arrival of special transports or visits from high-ranking Nazi functionaries. The inmates were also subjected to the photographer’s lens in humiliating situations such as the disinfection procedures. Here the event of being photographed became part of the degradation. The SS also used photos in an attempt to substantiate their racist concepts. Former inmate Fritz Lettow recalls: “One day all of the Jewish blocks had to remain standing at the gate. They were inspected and, here and there, a few names were jotted down. On the days that followed, they were photographed, keeping their zebra uniforms on for that purpose. Particularly hideous Jews, or those who looked especially Jewish, had intentionally been selected.”

Weimar military district headquarters, 19 September 1939

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1940

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1940

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1940

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 24 June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 9 March 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 27 June 1943

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 7 June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 14 May 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 12 August 1943

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 5 August 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 5 August 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 5 August 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

The former inmate Edo Leitner later described his work in the photo department. He was a member of the department staff from 1939 until the 1944 air raid, and its kapo from 1940. His duties included designing photo albums for the SS and documenting deaths and medical experiments.

On view here is a passage from the film Ich würde die Vergangenheit schon in Ruhe lassen, ... wenn sie mich in Ruhe lassen würde (1983) by Heidi Scholaen and Horst Haugg.

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1943/44

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1943/44

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, ca. 1940

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, November 1938

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, New York

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, November 1938

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, New York

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, November 1938

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, October 1939

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, October 1939

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 27 September 1939

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 27 September 1939

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, October 1939

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 7 September 1939

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, June 1938

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, November 1938

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, ca. 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Photographed Secretly

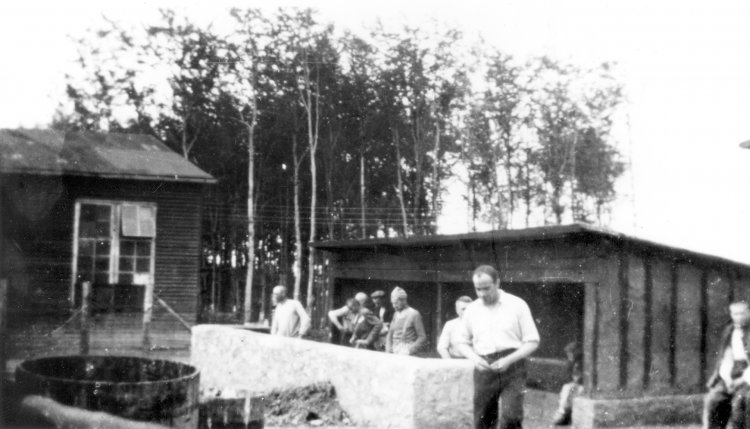

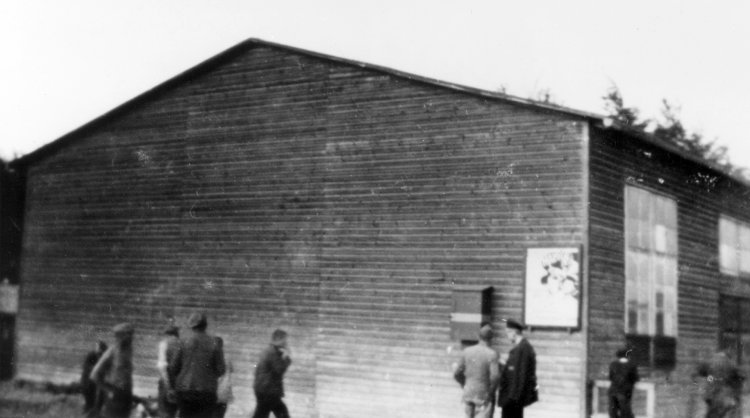

On a Sunday (a day off work) in June 1944, the Frenchman Georges Angéli stole a camera and secretly took eleven pictures in the camp. These photographs are the only ones showing the concentration camp from the perspective of an inmate.

Only photo department inmates had access to the cameras. Angéli, a trained photographer, took a discarded amateur camera from the attic of the office barrack along with two rolls of film for eight exposures each. His intention was to bear witness: “As regards the fact that I risked my life, that seemed minor to me in comparison to what the others had to endure. It was encouraging and exhilarating to be able to say to oneself that the risk one was taking might be of some use.”

There weren’t many guards in the camp on Sundays. In order to make himself inconspicuous, Angéli held the camera, which was wrapped in paper, under his arm or in front of his stomach. He also had three fellow inmates accompany him on his walk through the camp. Standing right in front of the camp gate, he even succeeded in photographing the crematorium. He also went into the overcrowded Little Camp, a quarantine and transit camp in which mass transports had just arrived from his native country. Since he could not look through the view-finder, several of the photos are tilted or out of focus.

Many of the pictures are astonishing, and do not correspond to our image of concentration camps. As a matter of fact, they actually do show the camp in an atypical situation: In June 1944 the inmates had a half to a whole day off every Sunday. The SS block and labour detachment officers were not in the camp on this day, and the inmates were permitted to use the time to rest a bit or even go for a walk. Angéli later retouched one of the photos for fear that the inmates seen lounging in front of the crematorium could create a false impression of life in the camp.

Angéli hid the rolls of film in a tin container along with extra copies of SS photos he had printed secretly. It was only after the liberation of the camp that he had the film developed and showed the pictures in small exhibitions in France.

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Georges Angéli, inmate, June 1944

Buchenwald Memorial Collection