The Liberated

Elie Wiesel

Survivors

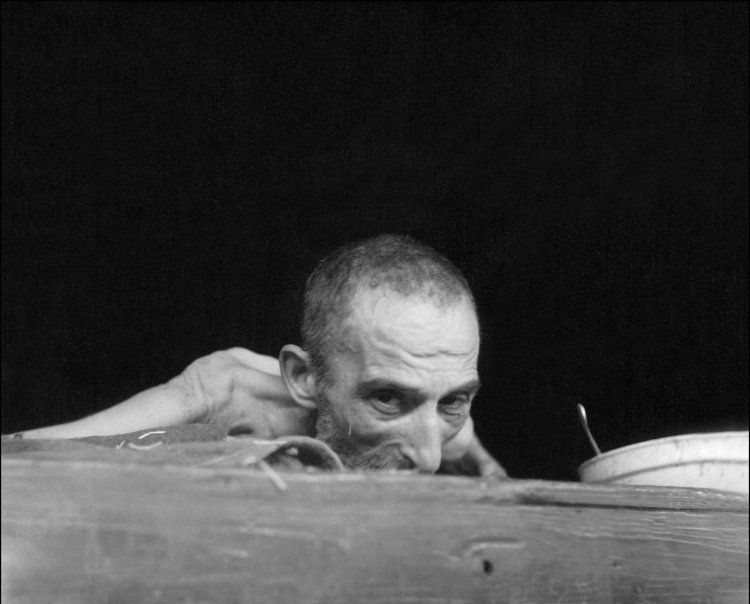

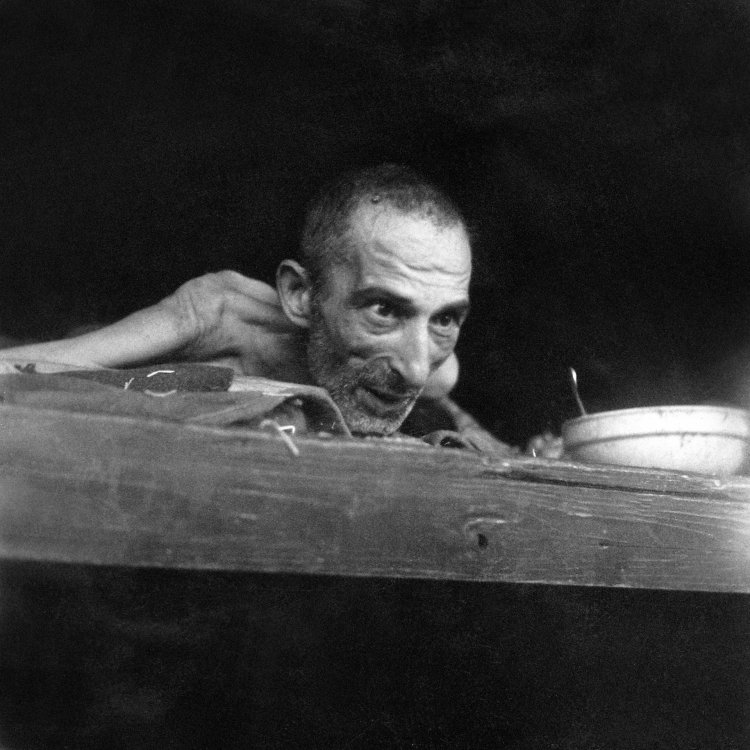

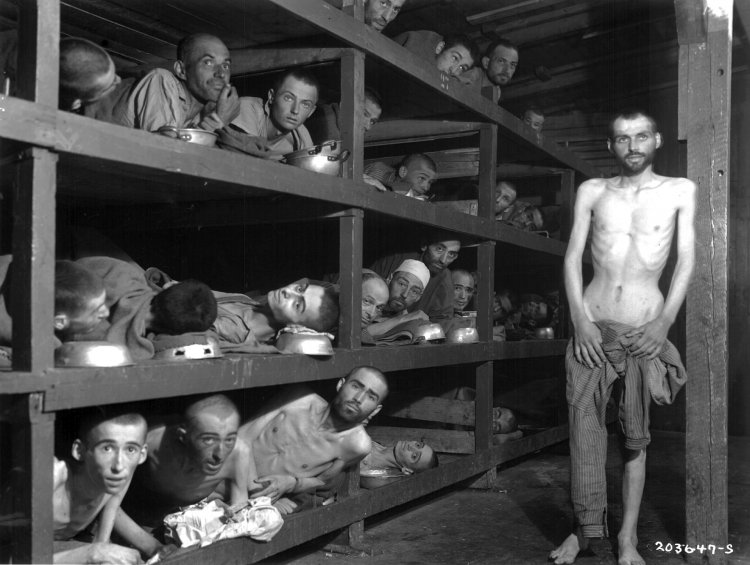

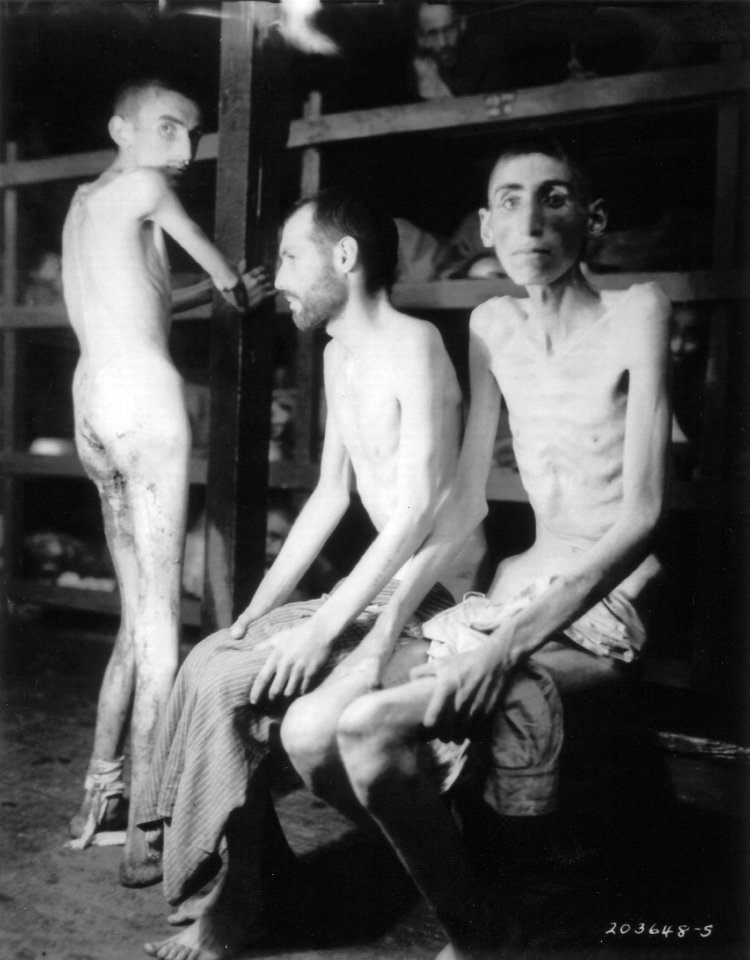

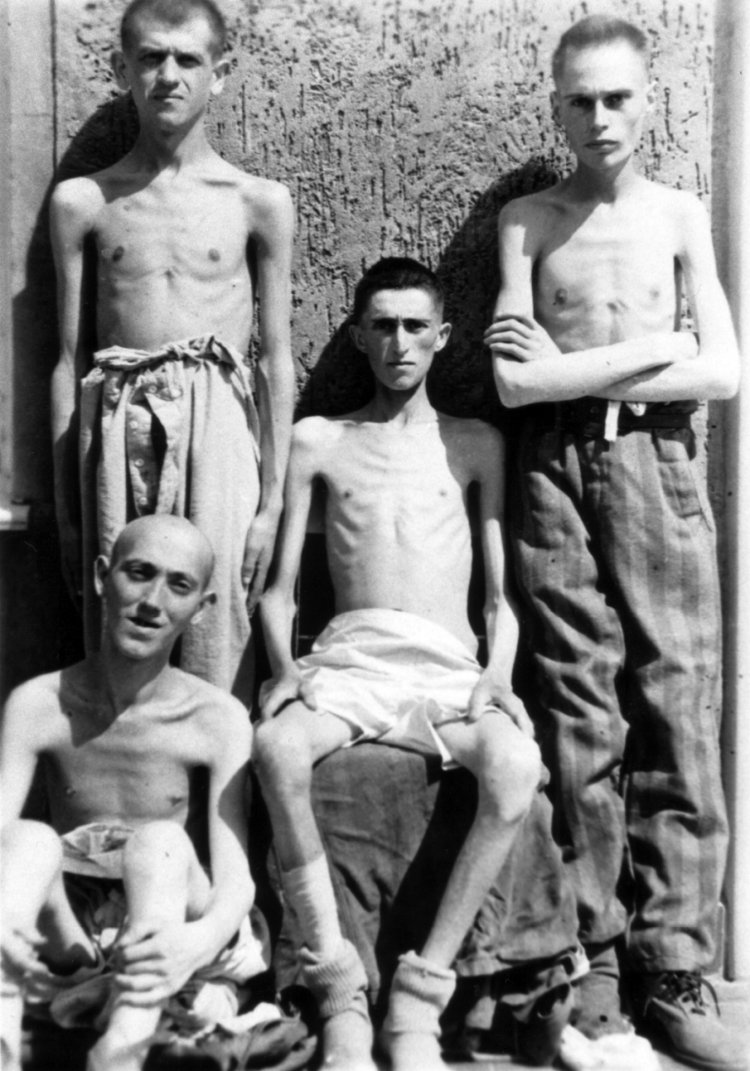

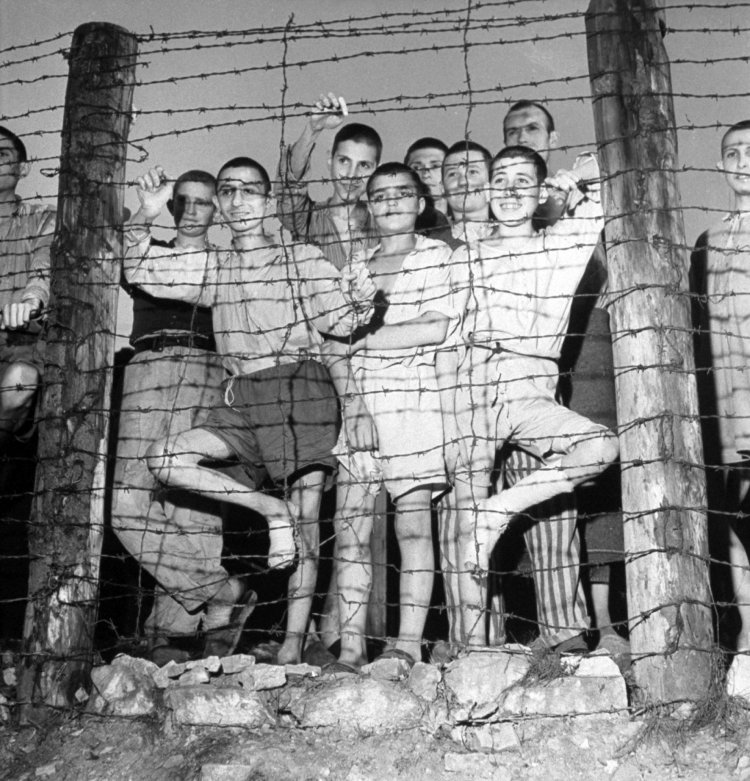

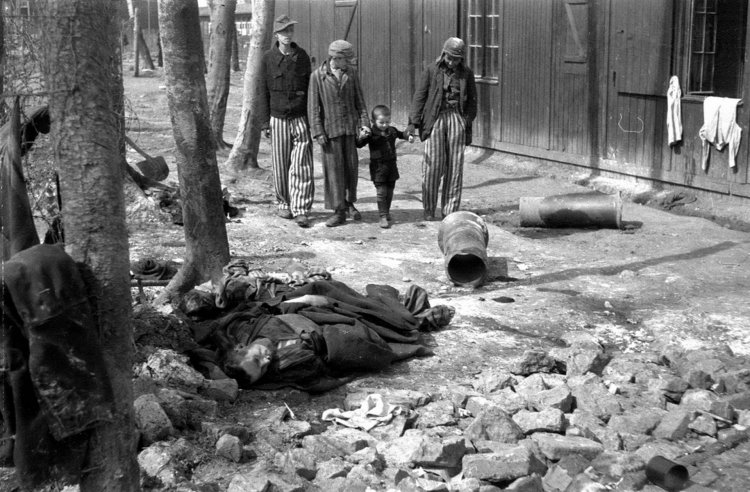

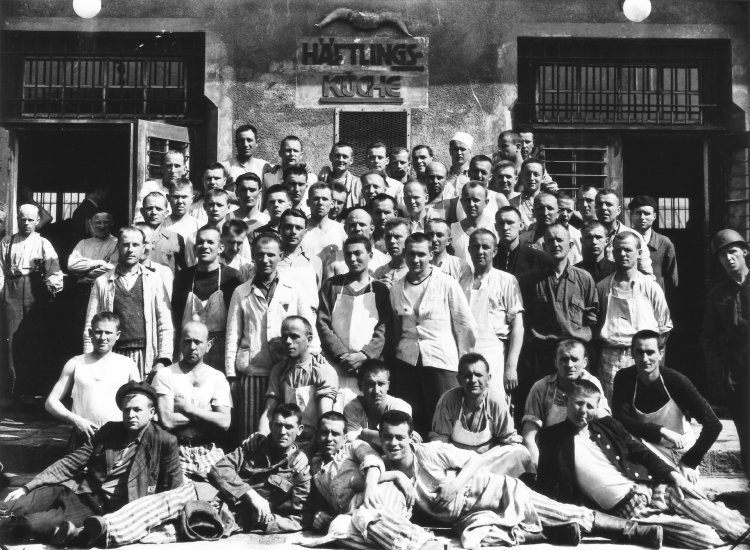

In Buchenwald, the American troops encountered a large number of concentration camp survivors for the first time. The photos of their emaciated bodies played a decisive role in the press coverage on Germany. Several of the pictures become symbols of the Holocaust.

Buchenwald was the first major concentration camp to be liberated by the American troops while it was still populated with inmates. To be sure, more than twenty thousand inmates had already been driven away on death marches, but nearly the same amount had remained behind in the camp. The Americans encountered survivors from the Soviet Union, Poland, France, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Spain, and many other countries. Among them were several hundred children and a large number of adolescents who had been deported to Buchenwald from the extermination camps in the east over the course of the preceding months. Aside from the parent camp with its exclusively male population, the Americans also liberated Buchenwald subcamps in which women had had to work for the German armaments industry.

The soldiers and journalists were particularly shocked by the sight of the Little Camp survivors with their skeleton-like bodies. They often referred to them as “the living dead”. The situation in which they found the former inmates appeared unfathomable. Due to the fear that mere verbal descriptions of Buchenwald might be dismissed as atrocity propaganda, the U.S. Army attached all the more importance to the official Signal Corps photos.

On 16 April, the military photographer Harry Miller was one of the first to take pictures of the former inmates in the barracks of the Little Camp. Among the inmates was Mel Mermelstein, eighteen years old at the time. He later recalled: “Then an order was given for us to file into the racks again. […] I rushed to the top of the rack, attempting to conceal myself from these people whom I knew nothing about. Then the flash of a light bulb went off and I quickly reacted by looking up to see what had taken place.” By April 29, the photo had appeared in the New York Times, and in June it was shown in an exhibition in Washington. The pictures taken in the Little Camp, the multi-bunks, the gaunt faces, the striped inmates’ uniforms, the barbed wire came to serve as symbols not only of Buchenwald, but of the Holocaust per se.

Walter Chichersky, U.S. Signal Corps, translation not found

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Éric Schwab, war correspondent, between 16 and 22 April 1945

Agence France Press/Getty Images, Munich

Éric Schwab, war correspondent, between 16 and 22 April 1945

Agence France Press/Getty Images, Munich

Harry Miller,

Harry Miller, U.S. Signal Corps, 16 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Harry Miller,

Harry Miller, U.S. Signal Corps, 16 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

120th Evacuation Hospital, between 15 and 23 April 1945

translation not found

120th Evacuation Hospital, between 15 and 23 April 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, beginning of May 1945

Stadtarchiv Reutlingen

Margaret Bourke-White, war correspondent, 16 April 1945

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images, Munich

Margaret Bourke-White, war correspondent, 16 April 1945

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images, Munich

Gérard Raphaël Algoet, Belgian army photographer, mid-April 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Gérard Raphaël Algoet, Belgian army photographer, mid-April 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Gérard Raphaël Algoet, Belgian army photographer, mid-April 1945

Ceges/Soma, Brussels

Gérard Raphaël Algoet, Belgian army photographer, mid-April 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Samuel Gilbert,

Samuel Gilbert, U.S. Signal Corps, 17 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Samuel Gilbert,

Samuel Gilbert, U.S. Signal Corps, 17 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Samuel Gilbert,

Samuel Gilbert, U.S. Signal Corps, 17 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Samuel Gilbert,

Samuel Gilbert, U.S. Signal Corps, 17 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

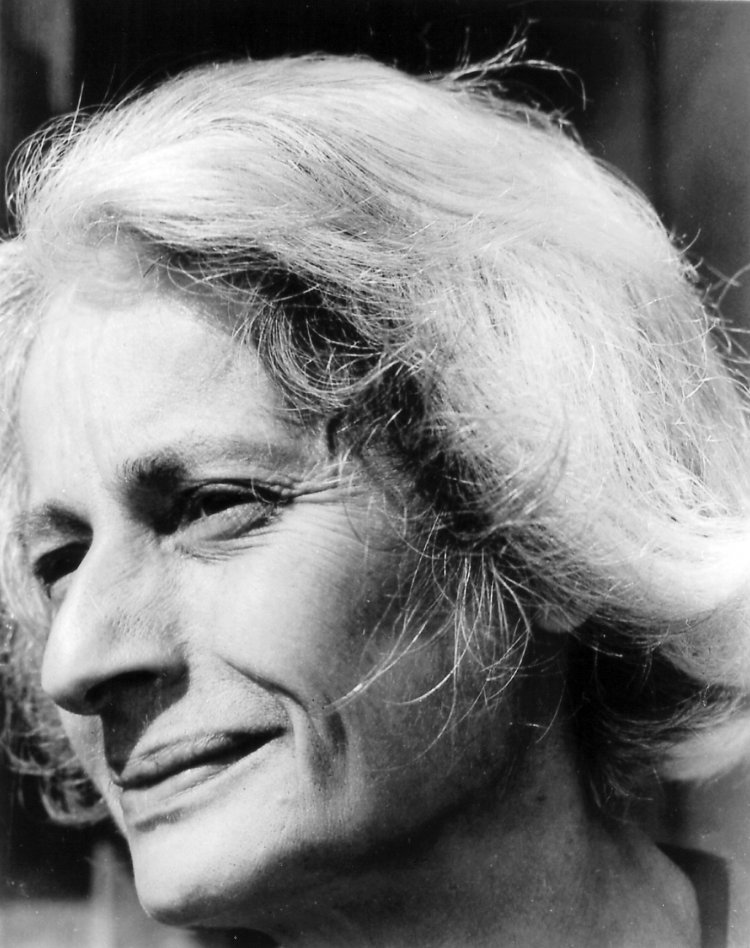

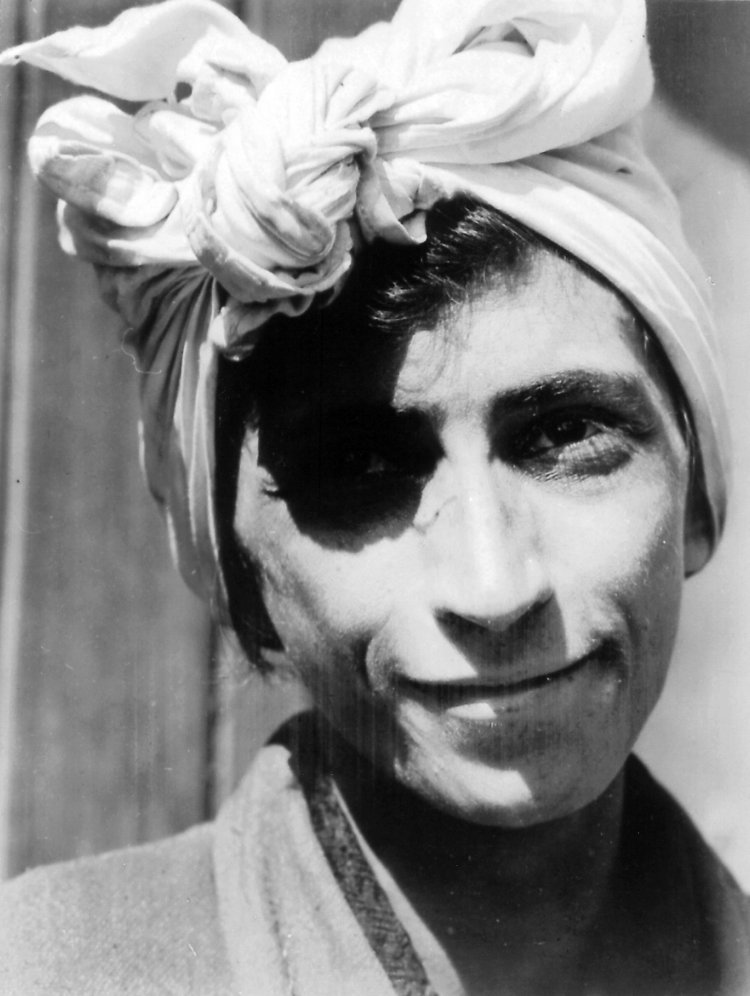

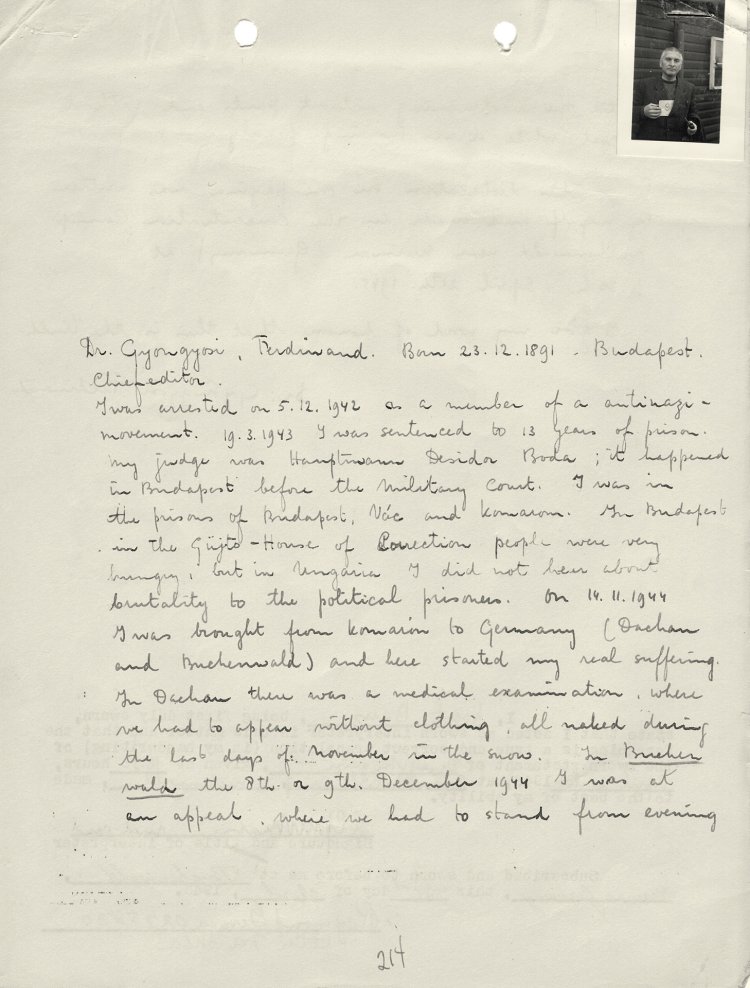

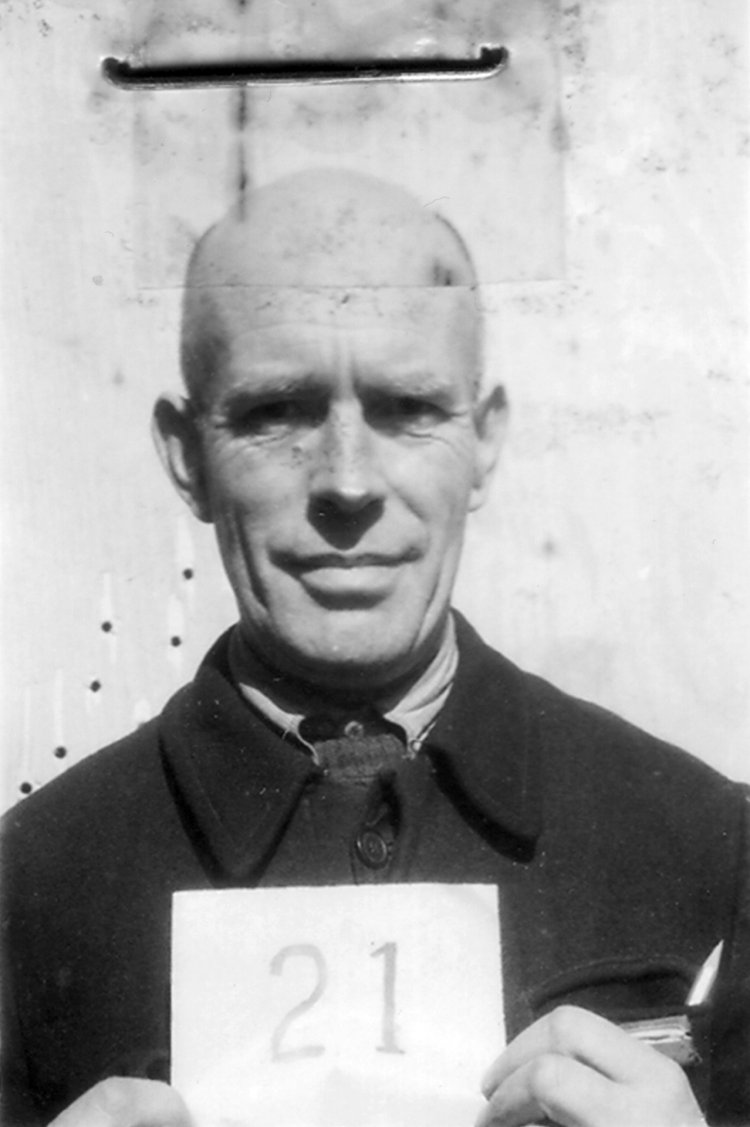

From Inmate to Witness

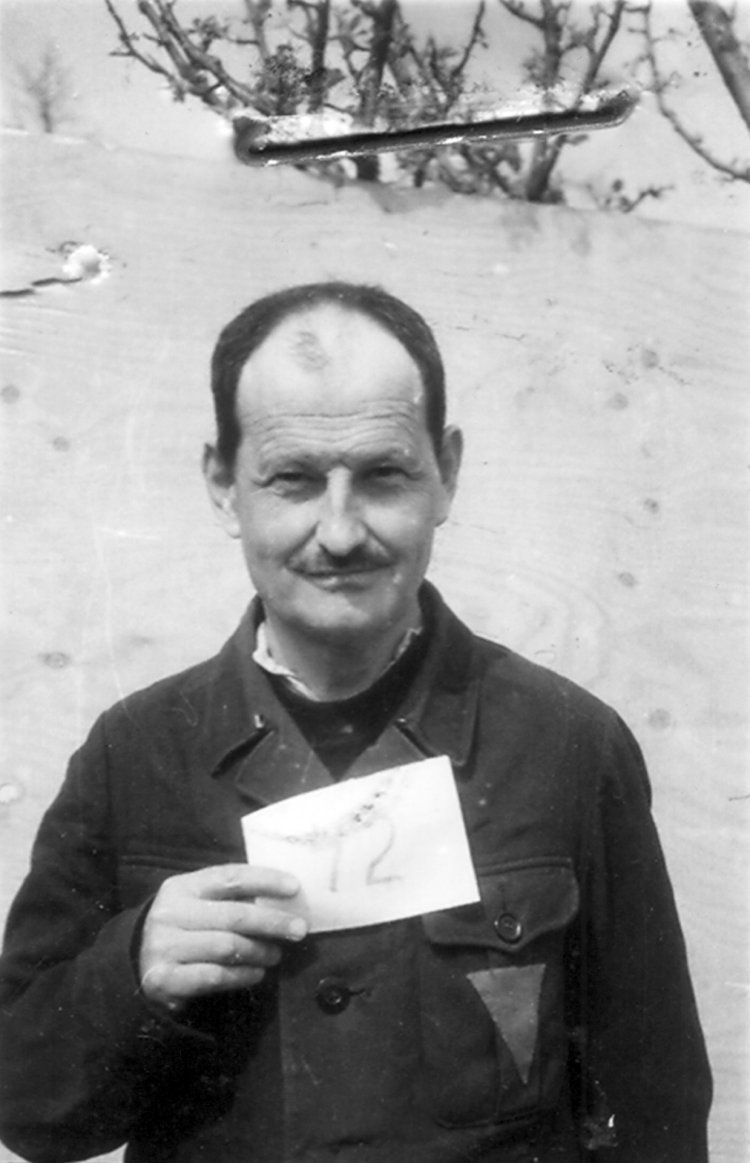

Even before leaving the liberated camp, 177 former inmates agreed to serve as witnesses in the future war crimes trials. As a means of authenticating their sworn reports, they were photographed by the soldiers of the American Signal Corps.

Immediately after liberation, the Americans began gathering evidence of the crimes committed at Buchenwald. In this context, decisive importance was attached to the testimony of liberated inmates. The U.S. army sent a group of interrogation officers, headed by Raymond C. Givens, to Weimar. Beginning on April 18, they swore in witnesses from fourteen countries. Particularly those survivors who had been confined in Buchenwald for many years were in a position to incriminate specific individual members of the SS.

Each witness stated his name, date of birth, city of residence, and profession and provided a brief account of his confinement history as well as of especially cruel behaviour by the SS which he had witnessed personally. The sworn statements were translated into English by professional interpreters and recorded in writing. They formed the most important basis for the proceedings carried out by the American public prosecutor’s department during the Buchenwald Trial in Dachau in 1947.

The interrogation officers worked with photographers of the 166th Signal Photo Company. They photographed the witnesses individually at first, and later – perhaps due to a shortage of film – in groups, each presenting a number by which he could be identified. After being developed and printed, the group photos were cut up and appended to the minutes of the respective testimony. The survivors in the photos meet our gaze as active witnesses, persons acting in their own interest. Although they still wear inmates’ uniforms, the expressions on their faces are no longer those of prisoners.

U.S. Army Europe War Crimes Branch, 21 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

U.S. Army Europe War Crimes Branch, 21 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

U.S. Signal Corps, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

U.S. Signal Corps, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

U.S. Signal Corps, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

U.S. Signal Corps, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

U.S. Signal Corps, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

U.S. Signal Corps, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

U.S. Signal Corps, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

“Building a New World”

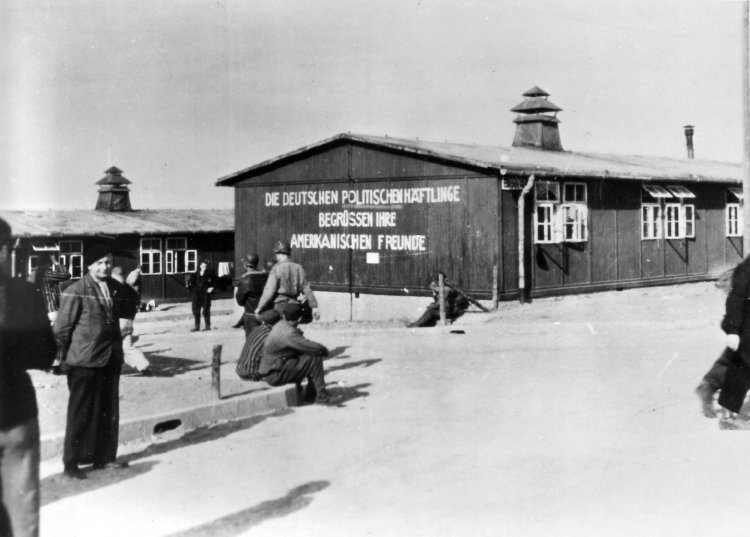

Immediately following liberation, many inmates became involved in political activities. The International Camp Committee, a resistance group formed while the camp was still in operation, organized demonstrations on the former muster ground.

On 11 April 1945, the Frenchman Paul Bodot, a sergeant of the U.S. Army, took a remarkable photo: outside the camp, armed inmates are seen capturing SS men who have attempted to flee from the advancing American troops. In the initial days following liberation, it was primarily former members of the inmates’ administration who played an important role not only in arresting SS guards but also in ensuring the supply of food and medicine.

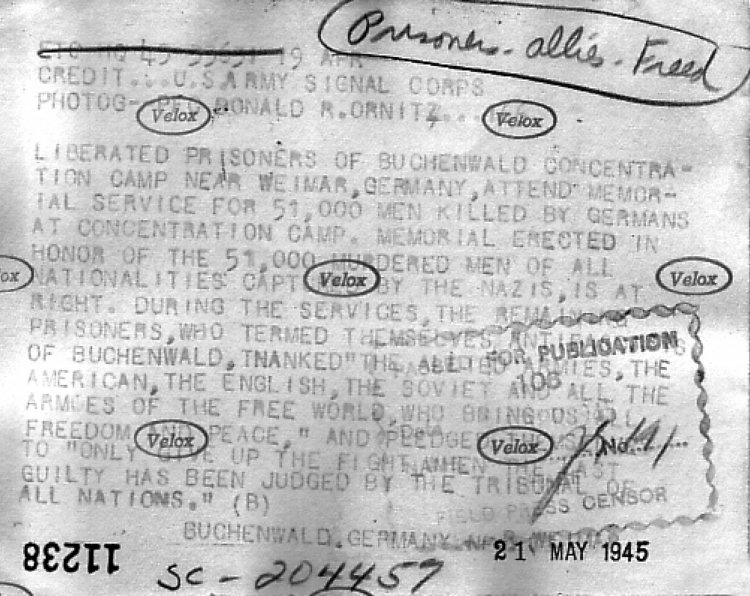

On 19 April, the International Camp Committee organized a memorial service for the dead of the concentration camp. The only still-extant photo of this event was taken by the American Signal Corps photographer Don Ornitz; it shows the participants assembling, divided into groups by nation. In his caption, the soldier quoted important passages of the speech, which ended with the “Oath of Buchenwald”.

In the weeks that followed, the former muster ground increasingly assumed the function of a forum for political gatherings. The major Labour Day celebrations taking place on 1 May were particularly well documented photographically. The photos, taken by the liberated inmates themselves, show the great efforts put into the preparations for the festivities: the barracks were decorated with slogans for the future Germany; the participants carried flags of their native countries and regions.

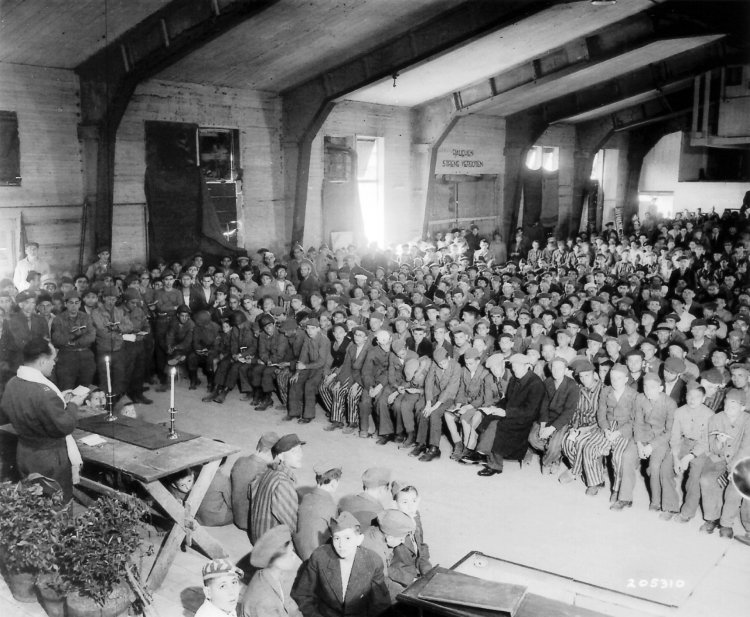

Not all of the former inmates took part in these activities. Particularly survivors of the Little Camp remained in the throes of death for weeks. There were approximately four thousand Jews of the most varied origins still in the camp. The American military rabbi Herschel Schacter organized well-attended worship services for them in the cinema barrack. These services were also an expression of the search for a common Jewish identity.

U.S. Signal Corps, U.S. Signal Corps, 19 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Paul Bodot, 3rd U.S. Army, 11 April 1945

Association Française Buchenwald-Dora, Paris

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, mid-April 1945

Geschichtsarchiv der Wachtturm-Gesellschaft, Selters

Donald R. Ornitz, U.S. Signal Corps, 19 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Photographer unknown, mid-April 1945 or later

Bettmann/Corbis

Photographer unknown, mid-April 1945 or later

Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

Adolf Dobschat, former inmate, 1 May 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Adolf Dobschat, former inmate, 1 May 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, 1 May 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Charles W. Herr, Jr.,

U.S. Signal Corps, 18 May 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Still from U.S. Army footage, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

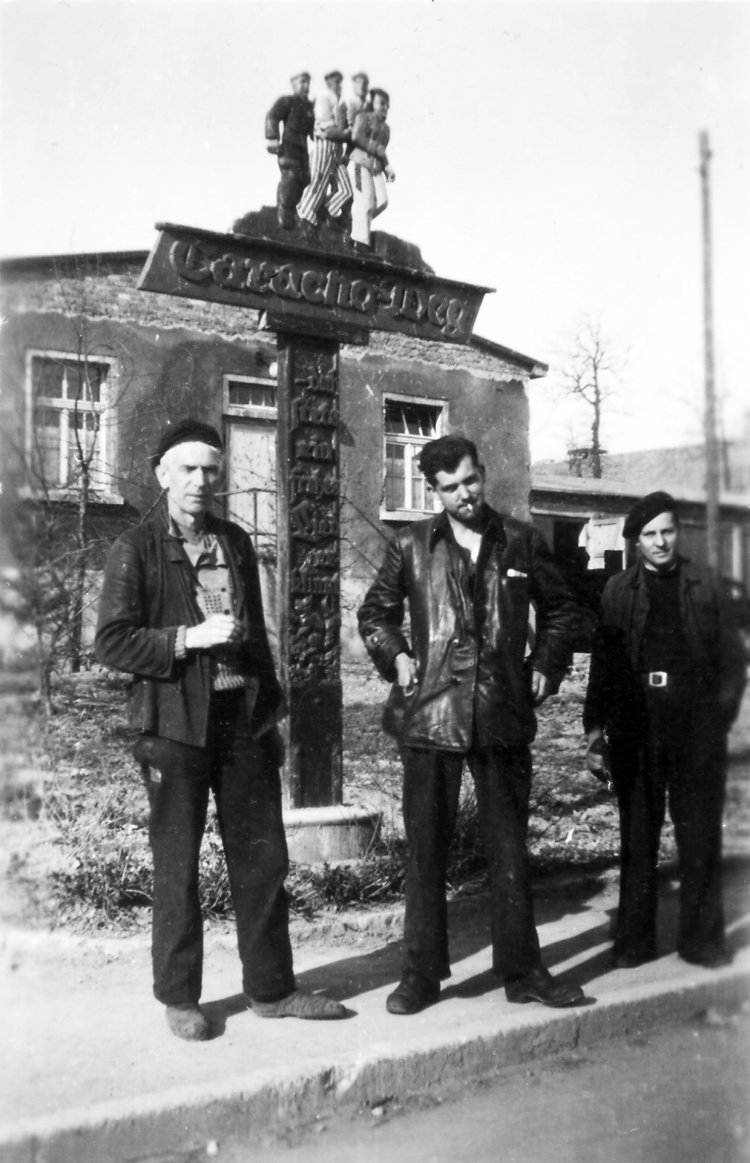

Before Departure

Before leaving the camp in April, May, or June 1945, many former inmates posed with their comrades for a souvenir photo.

Many liberated inmates had themselves photographed in groups before their departure. The pictures show people who sense a connection to one another for a variety of reasons: as co-members of a labour detachment, as political or religious brothers-in-arms, or simply as friends. Barbed wire, watchtowers, and barracks testify to the setting in which the pictures were taken – the liberated Buchenwald concentration camp.

It was above all Alfred Stüber who took these group portraits. As a member of the photo department staff, he was personally acquainted with many of the men seen in the pictures. He made prints of the photos for them to take home as reminders of the time shared in the camp. Whereas Stüber primarily photographed German groups, foreign photographers and delegates focussed on their respective compatriots.

The inmates’ departure stretched out over several months. The first to leave the camp were the French, on 22 April, followed by Belgians, Luxembourgers, Spaniards, Dutch, Norwegians, and Czechs. The first groups of Germans left in mid-May. Farewell photos were frequently taken immediately before departure. The bus, lorry, or train is ready and waiting.

From May until the camp was handed over to the Soviet Army on 4 July 1945, Buchenwald served as a displaced persons camp for former concentration camp inmates, prisoners of war, and forced labourers. Not all of them could be repatriated, i.e. returned to their native countries. Many Eastern Europeans, particularly Jews, were in search of a country that would take them in. The several hundred Buchenwald children, many of whom were the only ones in their families to survive, left the camp in June, headed for France, Switzerland, or Great Britain, where they were admitted to orphanages. For many, the orphanages were merely interim stops, followed by emigration to the USA or Palestine.

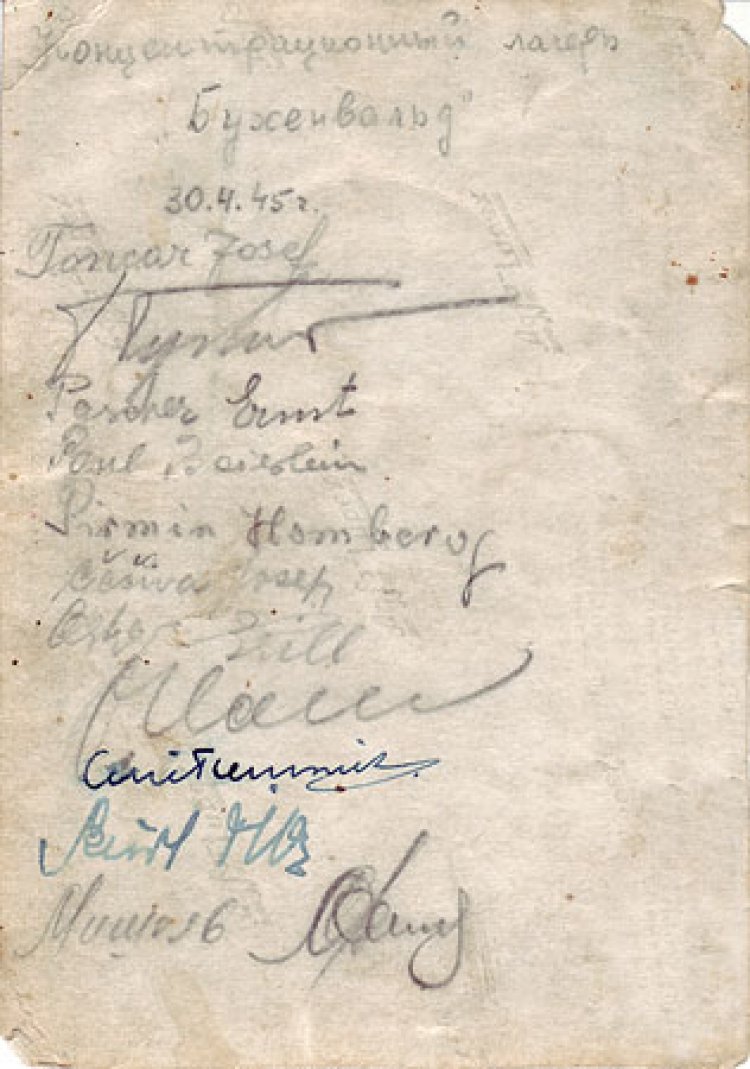

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, 30 April 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Photographer unknown, end of April 1945 or later

Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes, Vienna

Heinrich Albrecht, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Photographer unknown, 21 April 1945

Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes, Vienna

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

James E. Myers,

U.S. Signal Corps, 5 June 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Photographer unknown, 17 May 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Willem Hoogwerf, former inmate, June 1945

Private collection

Rubin Samelson, former inmate, May 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

International Red Cross, 17/18 April 1945

Comite International de la Croix-Rouge, Geneva

Photographer unknown, May 1945

Buchenwald Memorial Collection