The Camp as Evidence

John Edwin Thierman, U.S. Signal Corps

The Gathering of Evidence

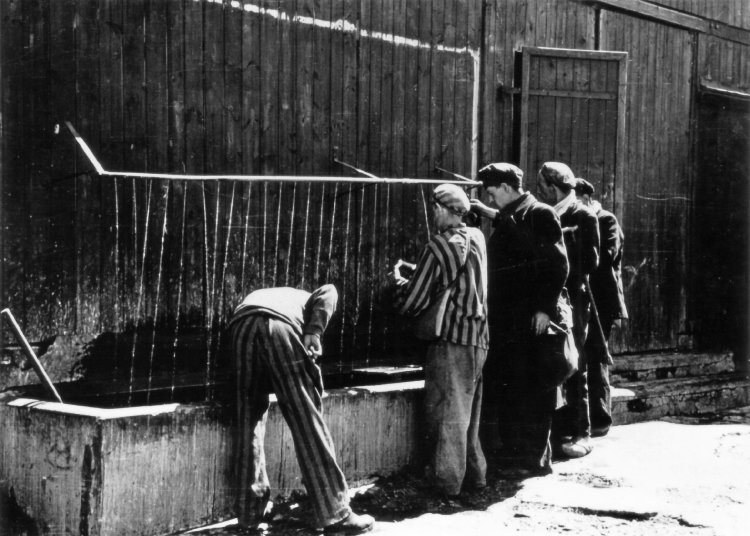

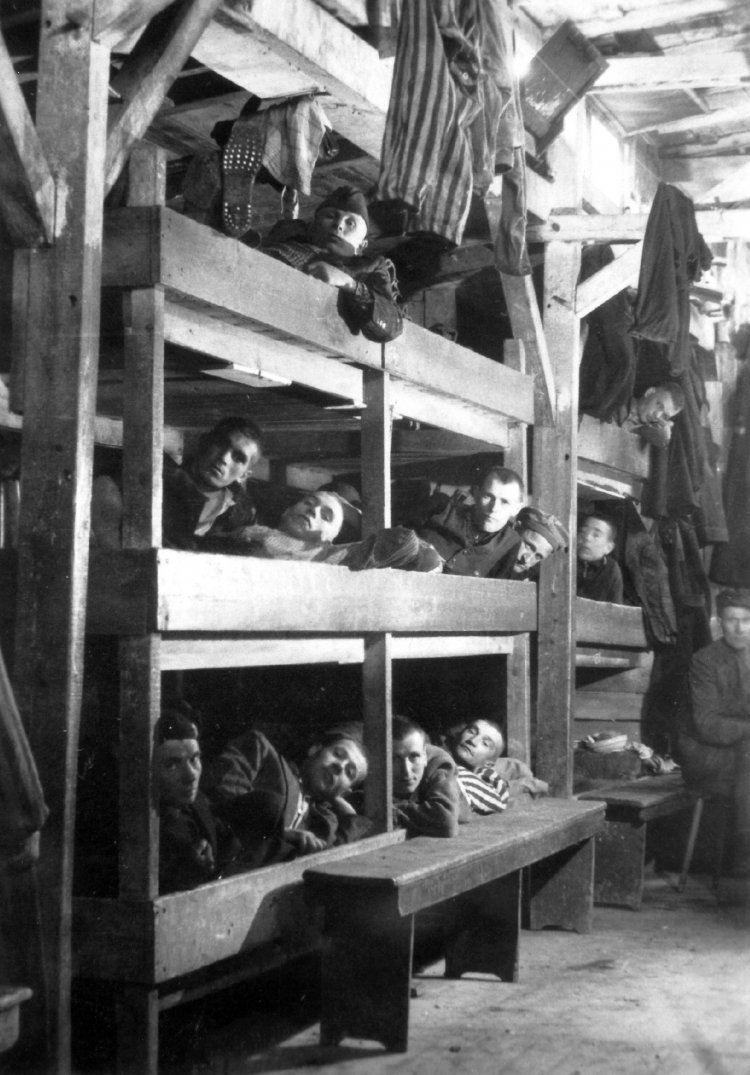

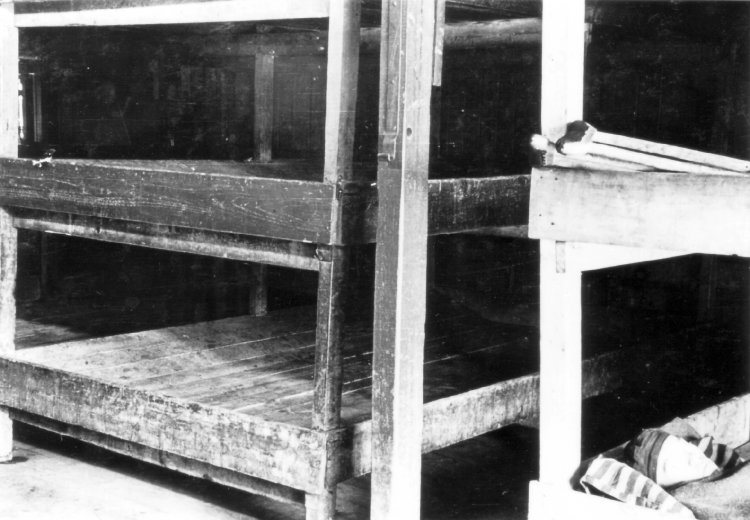

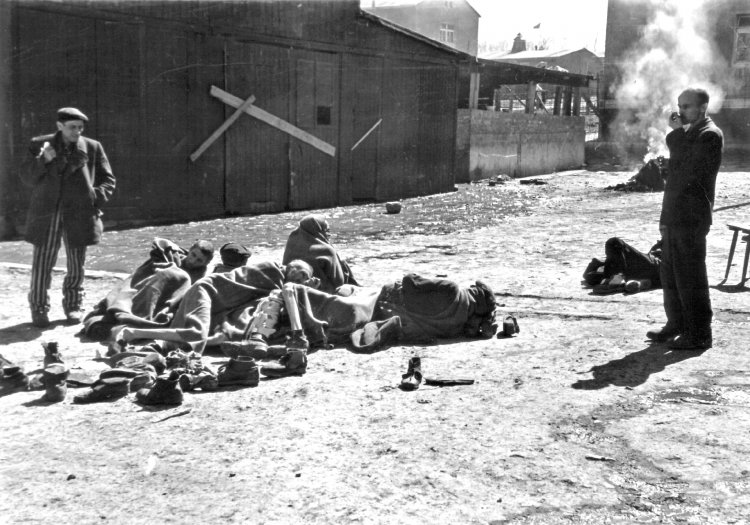

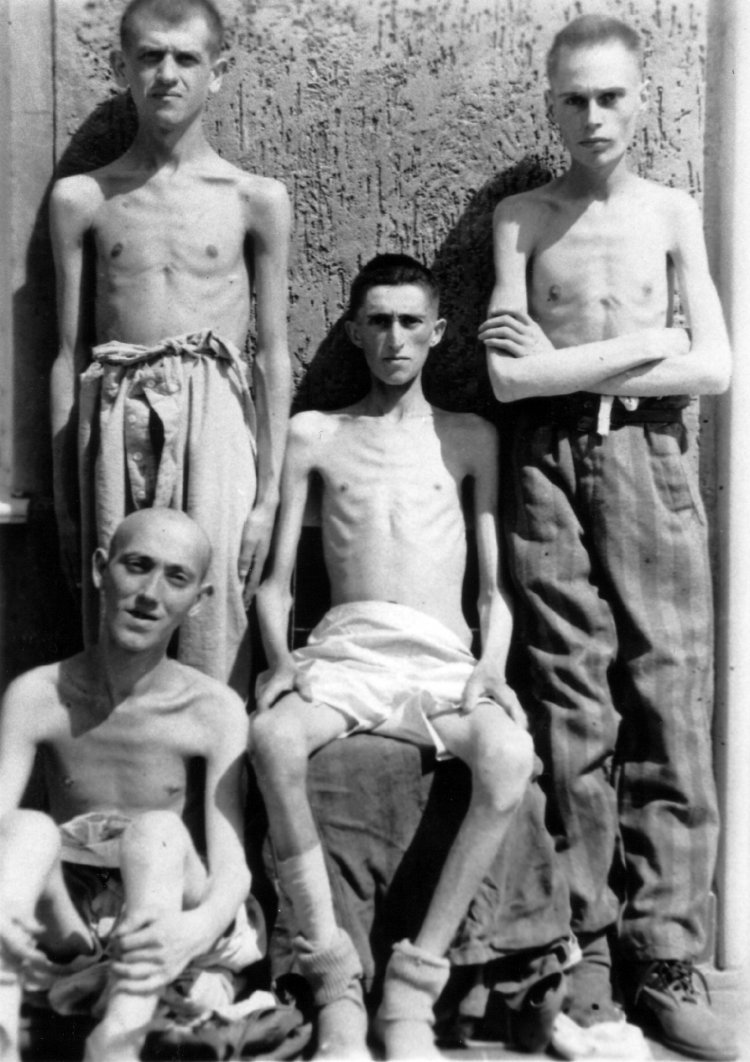

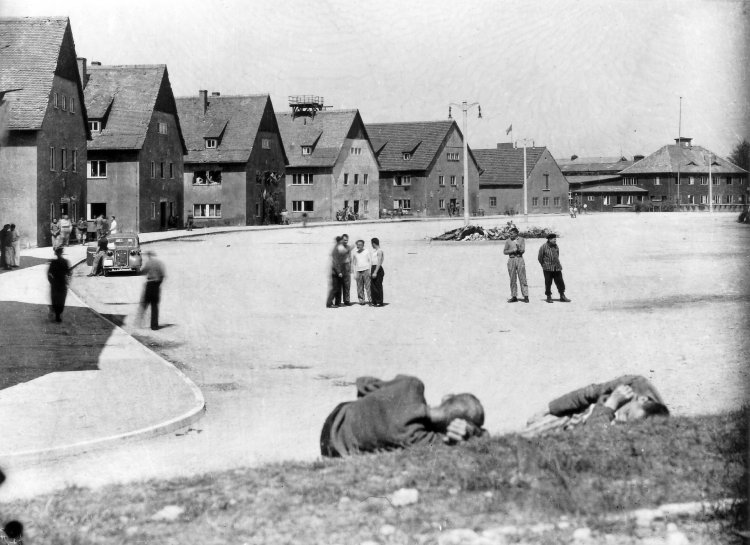

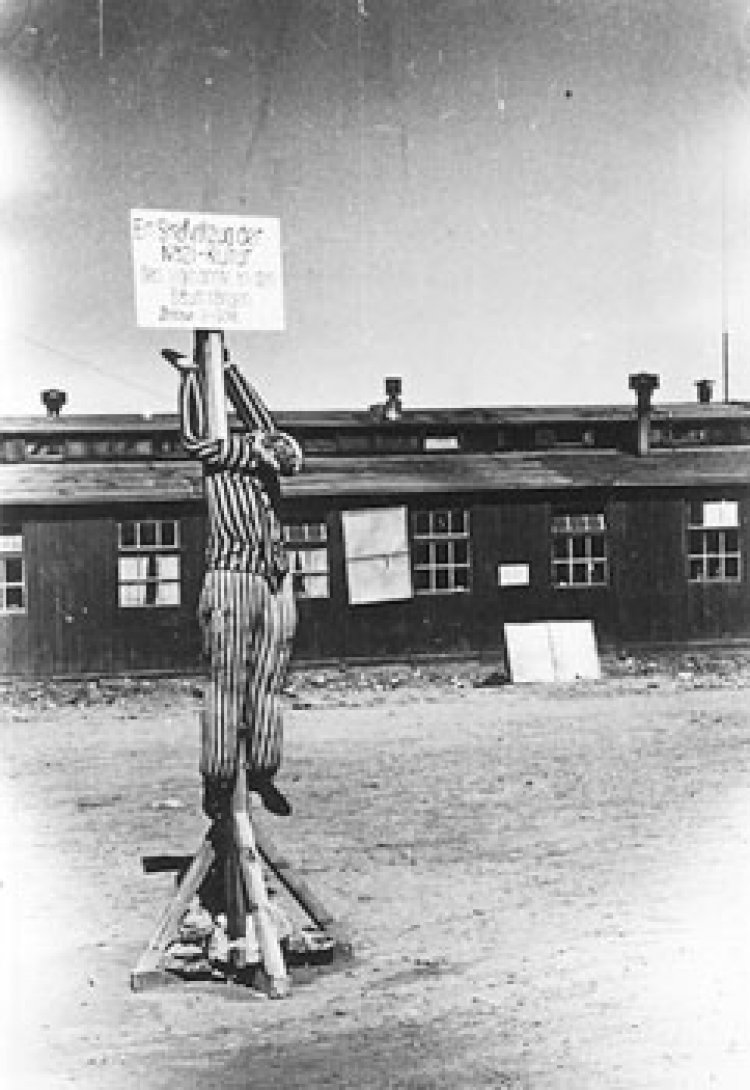

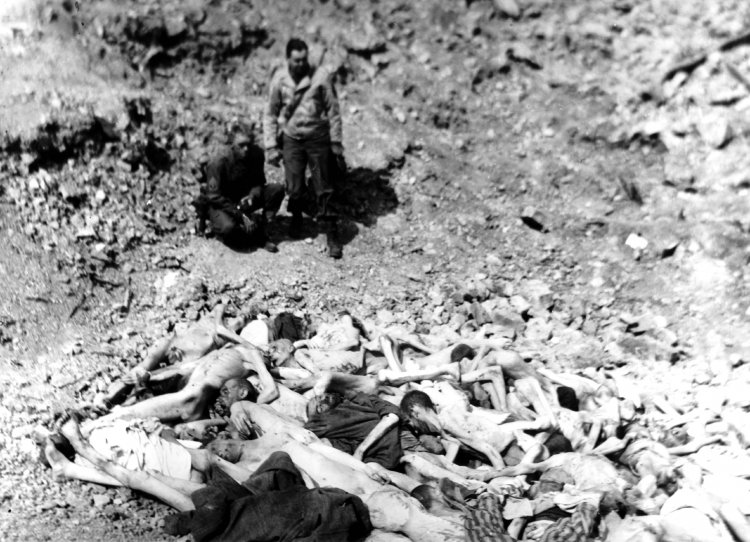

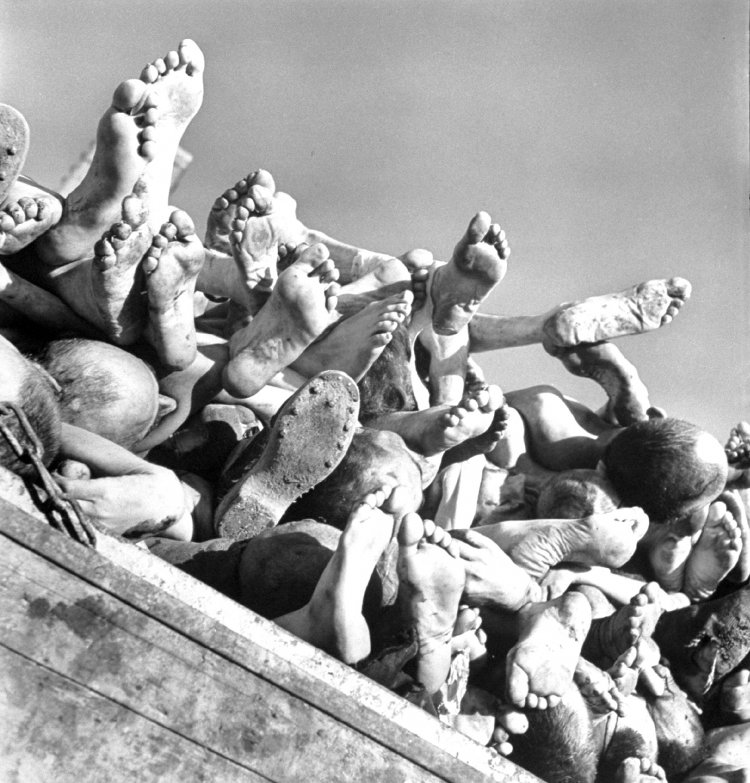

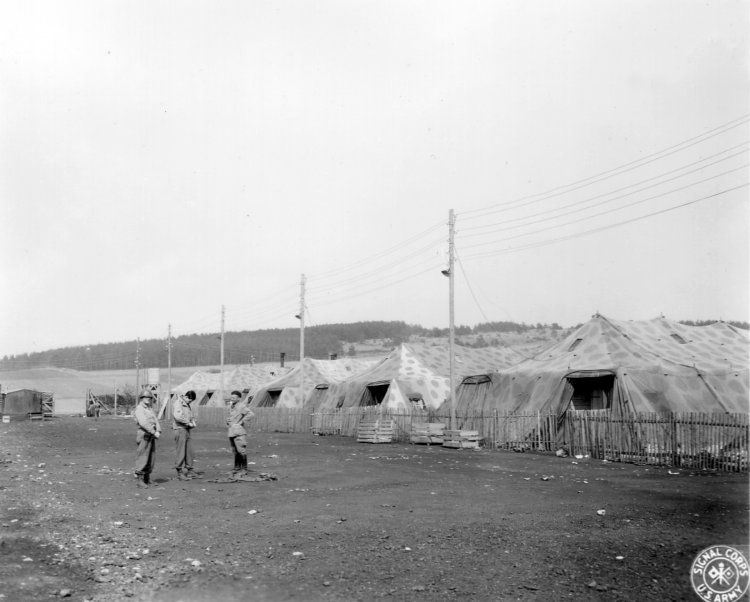

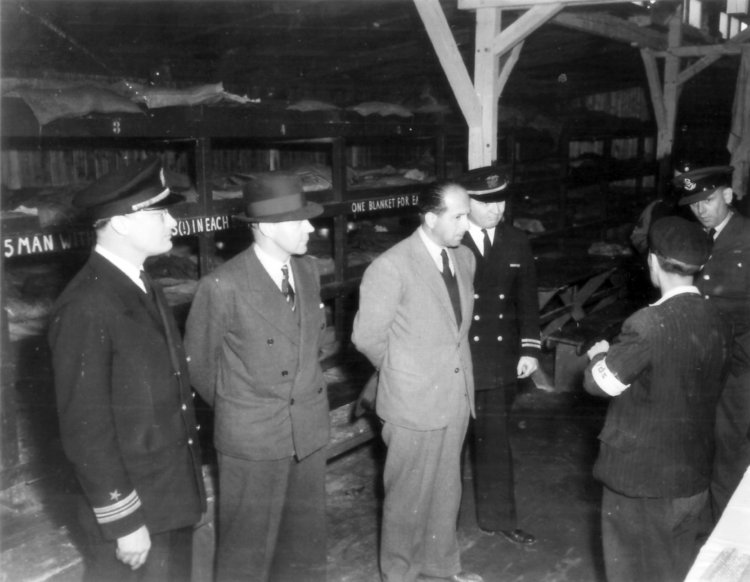

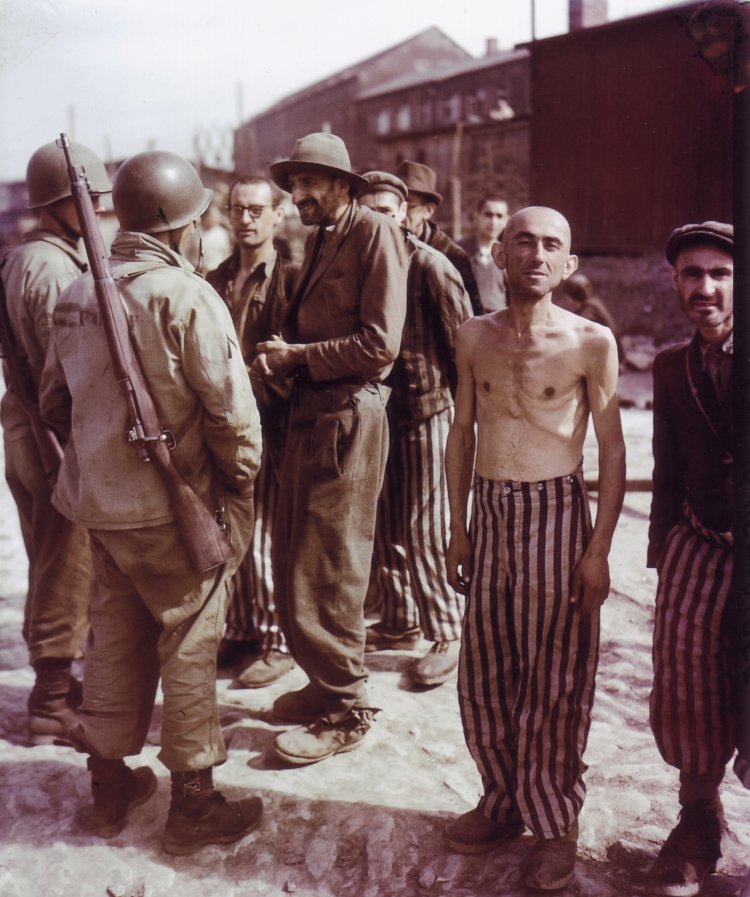

The first U.S. Army photographers reached the camp three days after the liberation of Buchenwald on 11 April 1945. The pictures they took were published all over the world and have continued to shape the public’s image of the concentration and extermination camps to this day. They also came to serve as evidence of the National Socialist crimes.

The war correspondents were as shocked as the American soldiers by the conditions they discovered in Buchenwald. Margaret Bourke-White, who worked for Life Magazine, later recalled: “I kept telling myself that I would believe the indescribably horrible sight in the courtyard before me only when I had a chance to look at my own photographs. Using the camera was almost a relief; it interposed a slight barrier between myself and the white horror in front of me.”

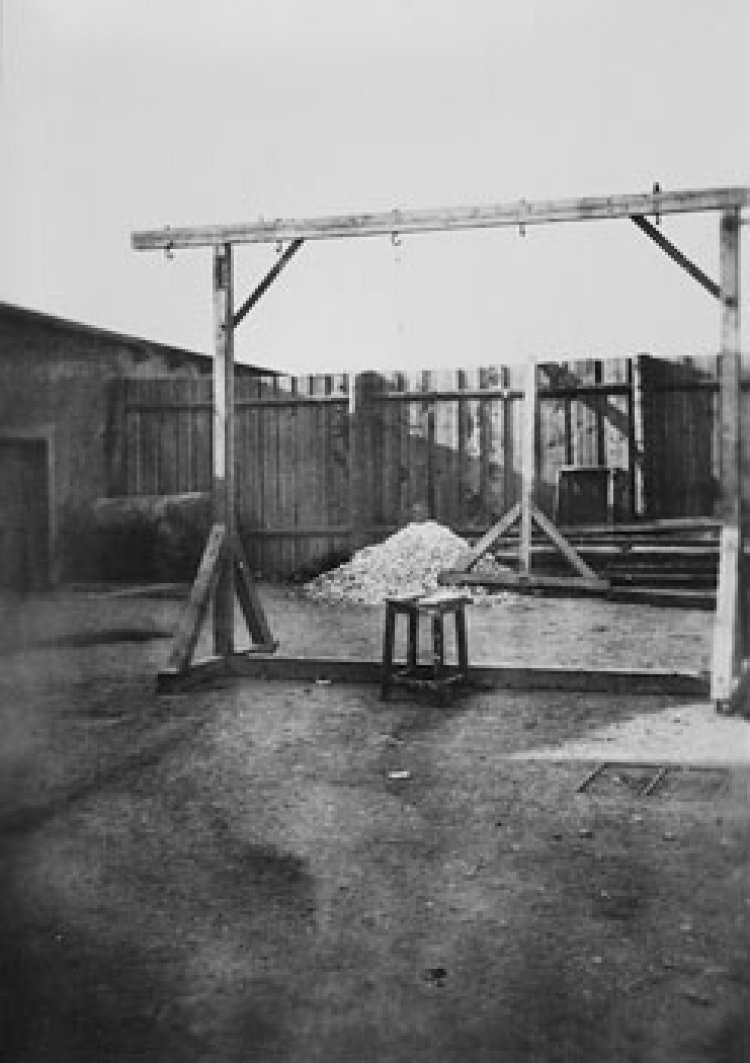

In addition to press photographers, army photographers from the 166th Signal Photo Company were at work in Buchenwald. The pictures taken by the latter were the first to pass military censorship and be telegraphed to all the countries of the world. As early as 19 April, the first photo of the Buchenwald crematorium courtyard – taken during the Weimar citizens’ tour of the camp on 16 April 1945 – was published in the London Times.

The military photographers’ most important task was to document the German crimes. Their photographs served as evidence for all persons not present in the camp as direct eyewitnesses, and were used in preparation for the war crimes trials. In 1947, the photographer Adrian J. Robertson was required to confirm the authenticity of the pictures he had taken in Buchenwald, which played a significant role in the Buchenwald Trial held in Dachau.

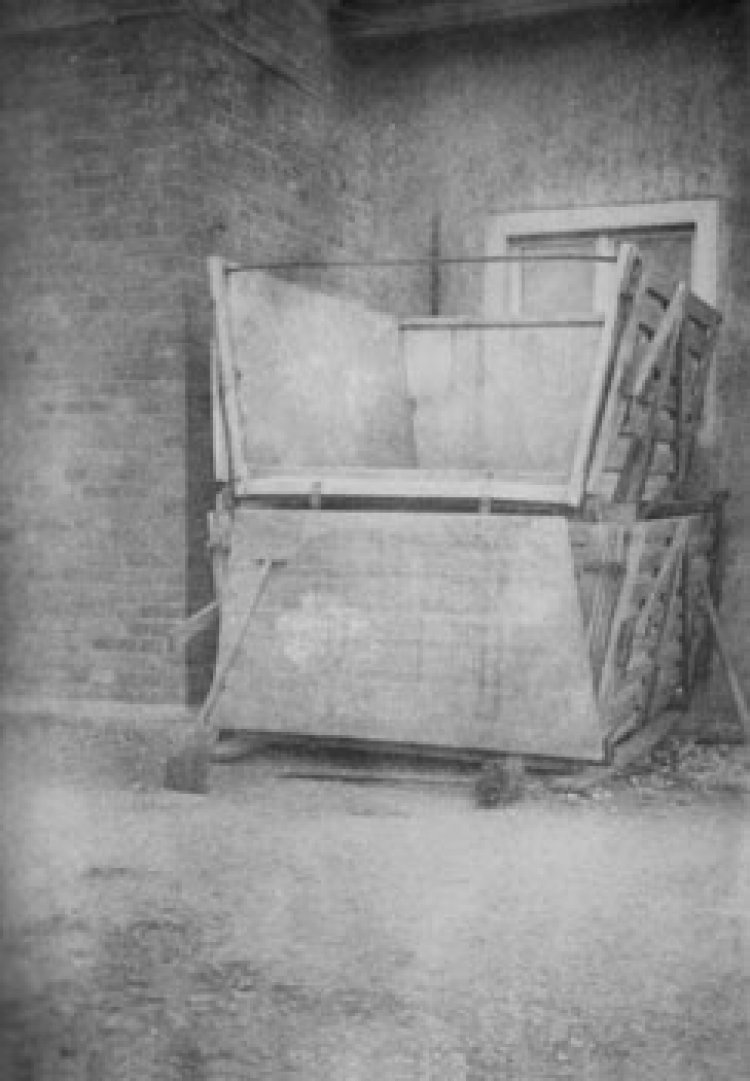

British and American parliamentary/congressional delegations toured the liberated camp. In addition to the appalling physical condition of the liberated inmates, it was primarily the heaps of corpses found on the camp grounds, the crematory ovens, and the mountains of bone ash that were seen as evidence of the “nazi horror mills” and thus became a symbol of the NS crimes and the Holocaust in general.

Parke O. Yingst, U.S. Army, 16 April 1945

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Walter Chichersky, U.S. Signal Corps, 14 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Photographer unknown, ca. 23 April 1945

Service Historique de la Défense, Vincennes

Walter Chichersky, U.S. Signal Corps, 14 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Walter Chichersky, U.S. Signal Corps, 14 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Walter Chichersky, U.S. Signal Corps, 14 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Margaret Bourke-White, war correspondent, 16 April 1945

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images, Munich

Margaret Bourke-White, war correspondent, 16 April 1945

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images, Munich

Arthur W. Stott,

Arthur W. Stott, U.S. Signal Corps, 13 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Arthur W. Stott,

Arthur W. Stott, U.S. Signal Corps, 13 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Arthur W. Stott,

Arthur W. Stott, U.S. Signal Corps, 13 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Arthur W. Stott,

Arthur W. Stott, U.S. Signal Corps, 13 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Charles B. Sellers,

Charles B. Sellers, U.S. Signal Corps, 20 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Howard E. James,

Howard E. James, U.S. Signal Corps, 15 May 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Howard E. James,

Howard E. James, U.S. Signal Corps, 15 May 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Seymour Schenkman, U.S. Army, 15 May 1945

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Howard E. James,

Howard E. James, U.S. Signal Corps, 15 May 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Edward Belfer,

Edward Belfer, U.S. Signal Corps, 17 May 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Seymour Schenkman, U.S. Army, 17 May 1945

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Edward Belfer,

Edward Belfer, U.S. Signal Corps, 19 May 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Louis Nemeth, U.S. Signal Corps, 26 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Byron H. Rollins, war correspondent, 21 April 1945

Bettmann/Corbis, Düsseldorf

Adrian H. Robertson, U.S. Air Corps, after 11 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Rex L. Diveley, Rehabilitation Service, 16 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Rex L. Diveley, Rehabilitation Service, 16 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

On Behalf of the Camp Committee

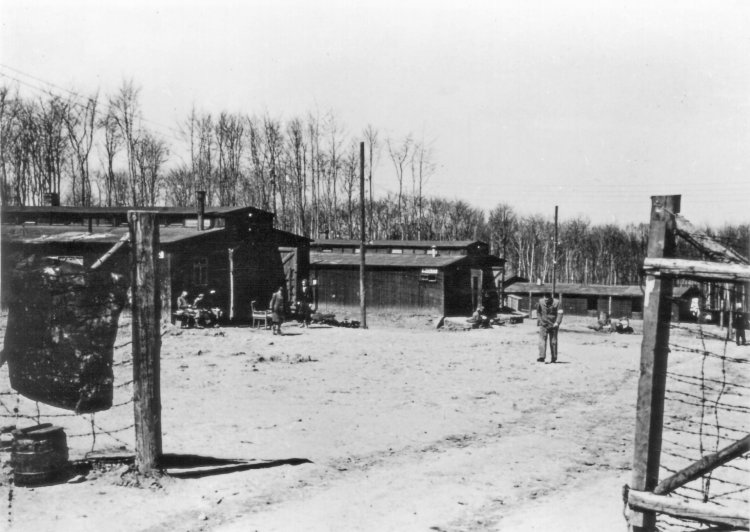

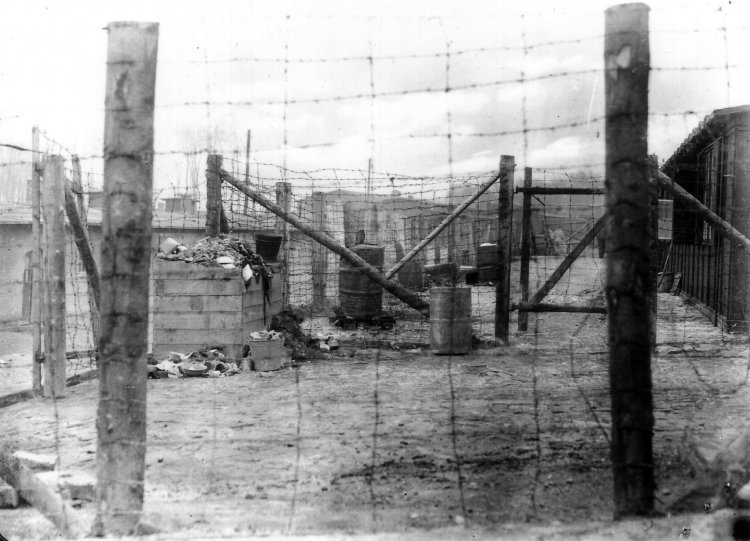

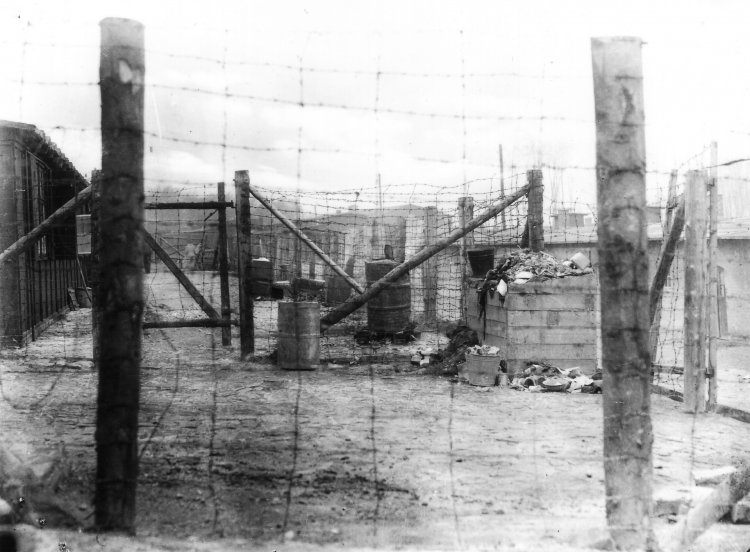

Not only American soldiers and war correspondents took pictures in Buchenwald, but the survivors also documented the former concentration camp. They photographed parts of the camp whose significance as the scenes of crimes committed at Buchenwald is not immediately apparent.

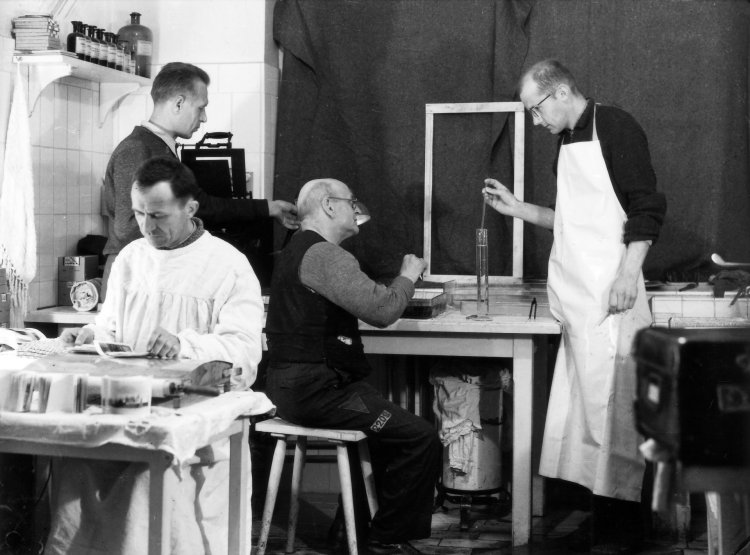

Alfred Stüber and Heinrich Albrecht were Jehovah’s Witnesses who worked in the photo department. On 20 April, the International Camp Committee commissioned them to document the Buchenwald concentration camp. Their work resulted in a series of more than seventy photos providing a well-differentiated view of the camp.

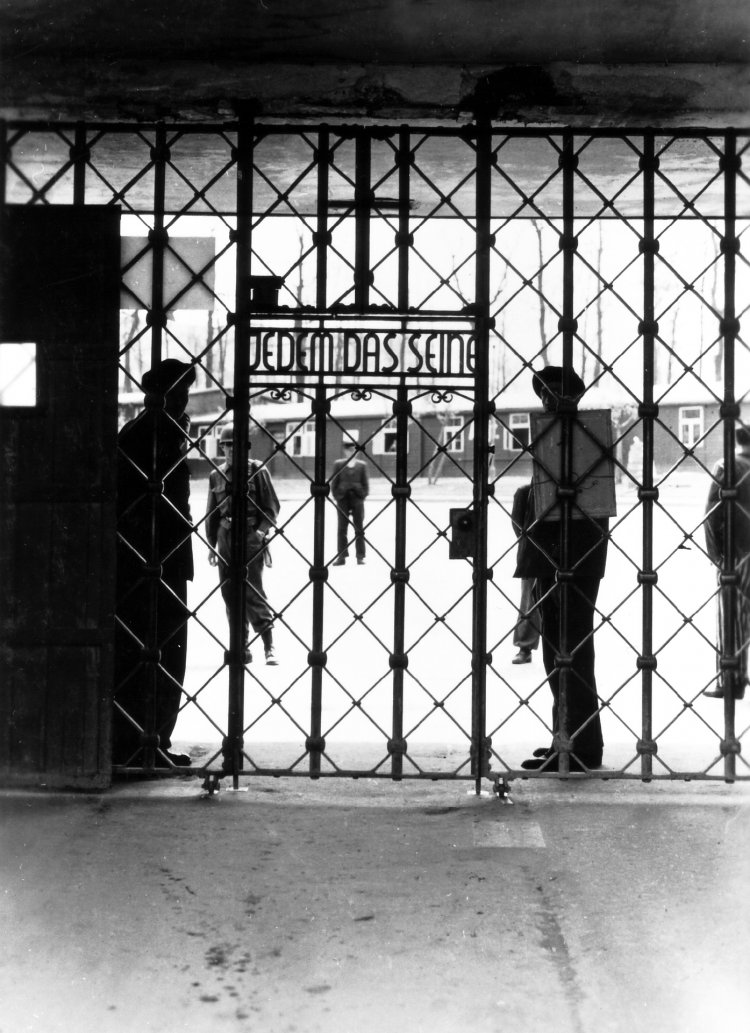

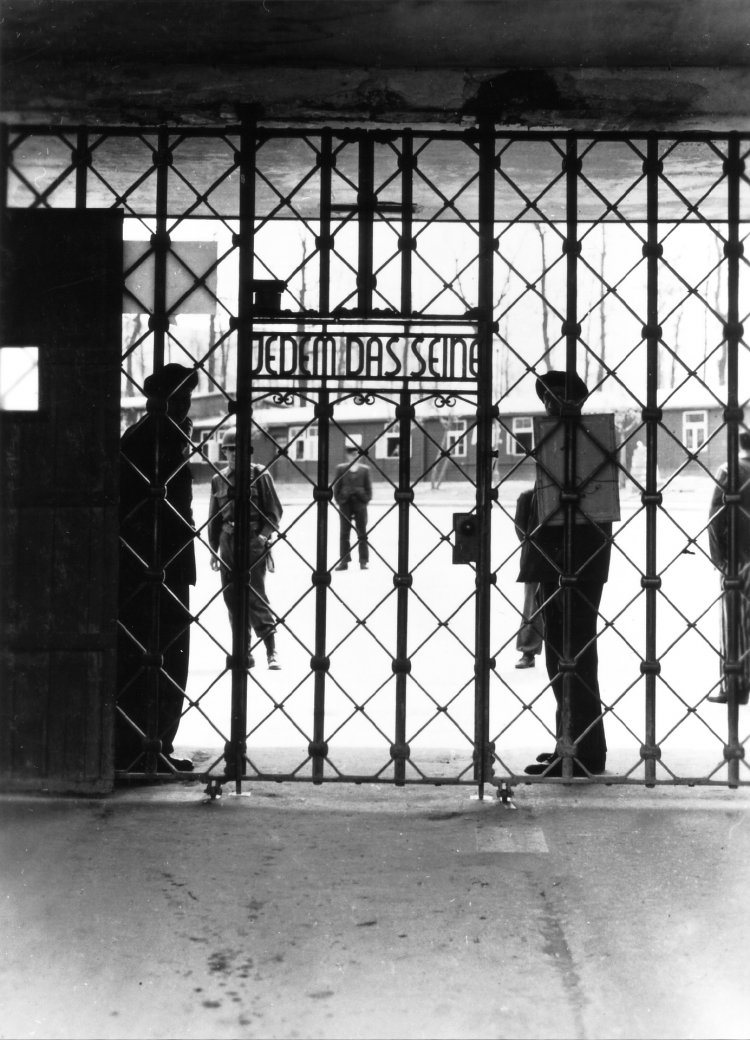

The crematorium, the corpses in the crematorium courtyard, and the suffering of the inmates in the Little Camp were likewise of central significance for Alfred Stüber and Heinrich Albrecht. They documented the former stable in which SS men had shot more than seven thousand Soviet prisoners of war to death, and the operating room II of the inmates’ infirmary, where SS physicians had killed hundreds of inmates. Stüber and Albrecht thus secured impressions of places outsiders could not possibly know about. Their pictures also recorded the world of their tormentors – the camp commander’s mansion and the SS falcon yard. They photographed the gate building and its cast-iron entrance gate with the inscription “Jedem das Seine” (To Each His Own). The words faced the inside so that the inmates could read them from the muster ground.

In April and May 1945, this photo series was reproduced and distributed to several hundred survivors in the liberated camp. When they returned home, they were to report on the crimes committed at the Buchenwald concentration camp and use the photos to provide evidence of the conditions in the camp. The pictures appeared in countless publications by former inmates all over the world.

Alfred Stüber drew from these photos to compile a slide show and lecture which he held primarily in Southern Germany beginning in July 1945. He began his talk with the words: “In the pictures now to be shown, you may see for yourselves what kinds of places these camps really were.”

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber, former inmate, after 20 April 1945

Private collection

Alfred Stüber: The Endless Path

Beginning in July 1945, the former inmate Alfred Stüber held slide lectures in various cities to inform the public about the Buchenwald concentration camp.

At these well-attended lectures, the first few pictures were accompanied by Beethoven music; then Albrecht Stüber began to talk in a quiet voice. A newspaper article reported on the “breathless suspense” among the members of the audience, and the “murmur of horror and outrage”. On July 14, while the lecture was being held in Reutlingen, an SS man from Buchenwald was presented to the audience. He confirmed the truth of Stüber’s descriptions and the authenticity of the pictures shown. Here you see an abridged and reconstructed version of the lecture in which the photos are combined with the texts of the original manuscript.

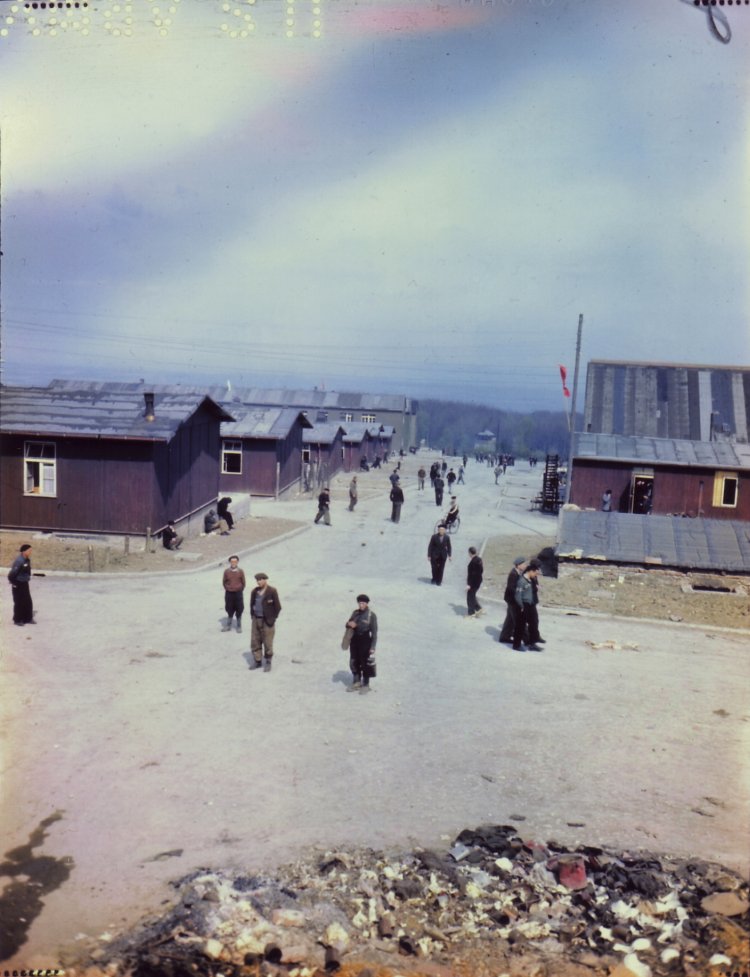

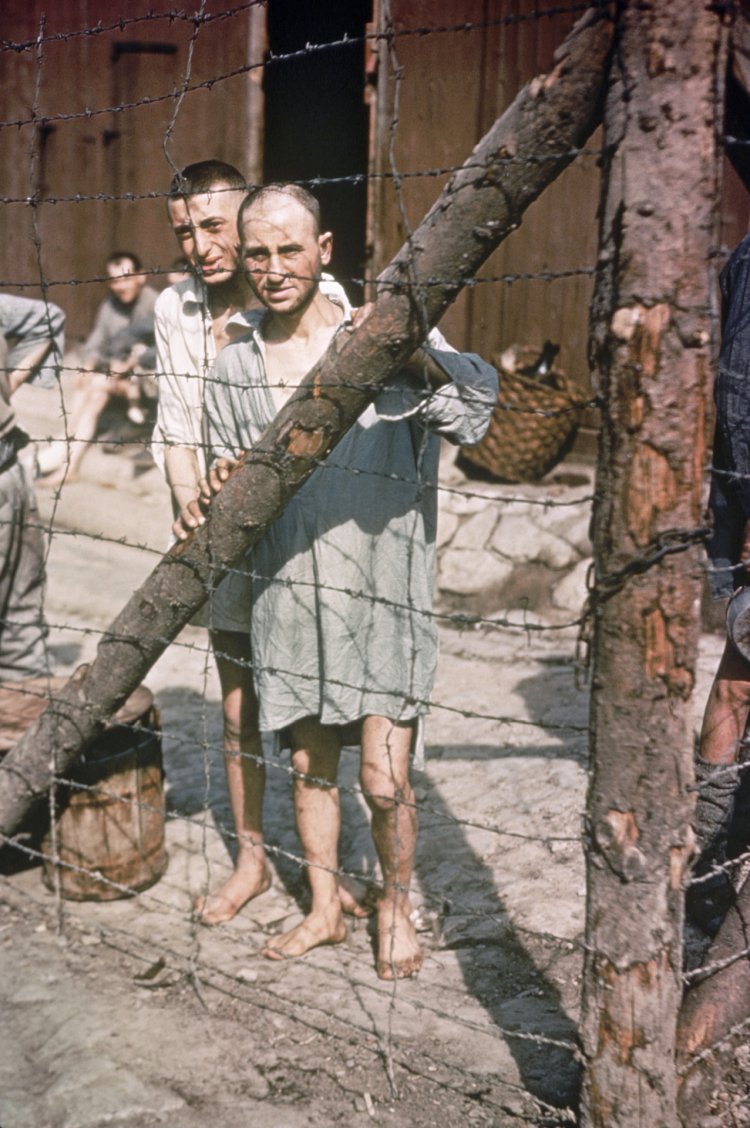

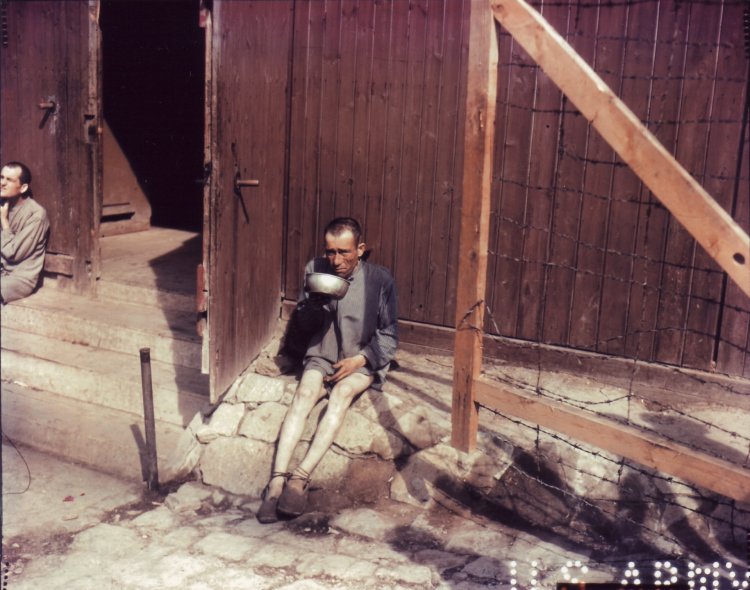

Buchenwald in Colour

A series of thirteen colour slides of the liberated camp has survived. They were taken by Ardean R. Miller, one of the U.S. Army’s total of only four colour photographers in the European theatre of war. He was at Buchenwald on 18 April 1945.

Ardean R. Miller was the American army’s most experienced colour photographer. He had already been working with the colour films developed by Kodak since the late 1930s. Miller later said that the order to photograph Buchenwald was the worst he received. The images haunted him his whole life long.

For the U.S. Army, the employment of colour photography in 1945 was an experiment to which not much significance was attached. The pictures taken by Ardean R. Miller were not put to use for many years. It was not until the 1990s that they were rediscovered and published.

Today, the series grants the spectator special visual access to the liberated camp. Whereas in the black-and-white photos a sense of temporal distance and a documentary character are prevalent, the colour photos create a surprising closeness to reality, making Ardean R. Miller’s slides unique images of the days following the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp.

U.S. Signal Corps, U.S. Signal Corps, 1944/45

Private collection

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

translation not found

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Ardean R. Miller III, U.S. Signal Corps, 18 April 1945

National Archives at College Park, Maryland