The Camp

Fred Wander

The Camp’s Construction

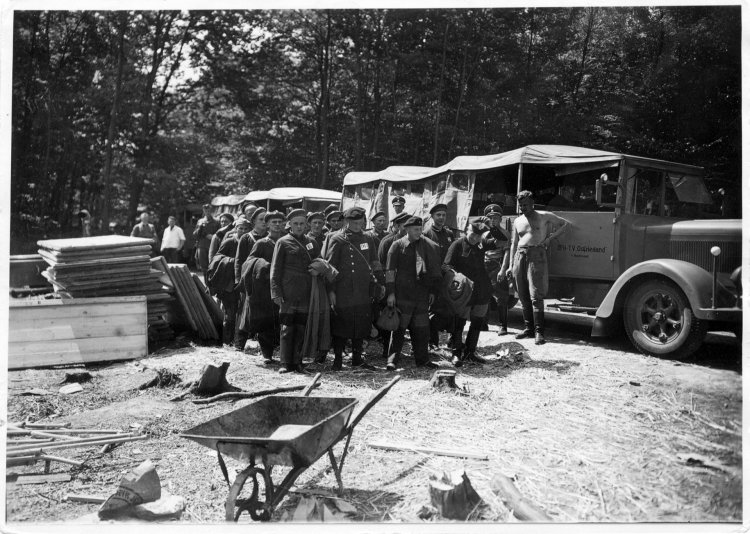

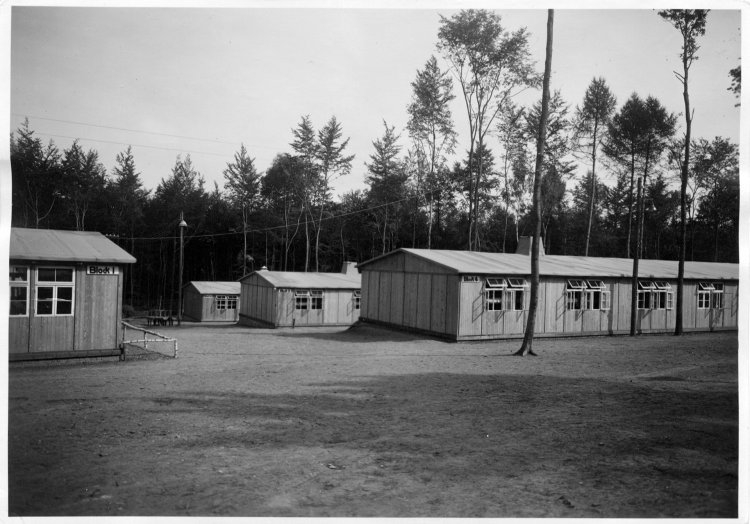

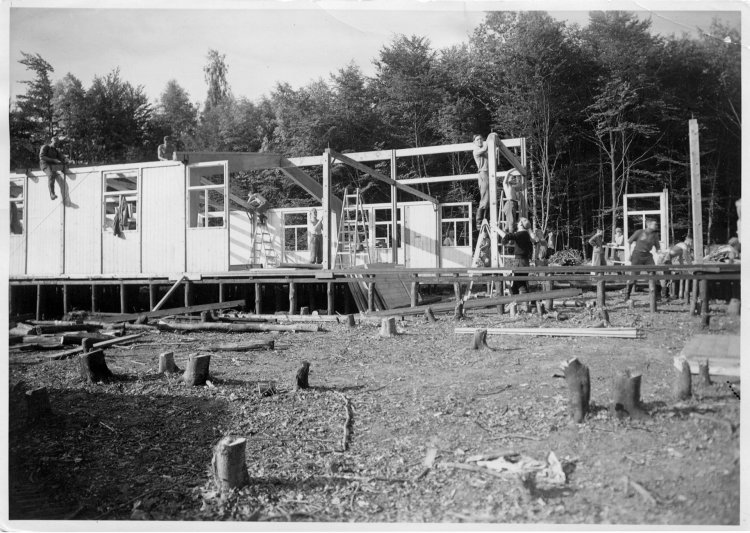

When the SS brought the first inmates to Ettersberg Mountain near Weimar on 15 July 1937, the concentration camp did not yet exist. The inmates had to build it themselves. Until 1945, the SS had the camp continually developed and enlarged, and the various construction phases meticulously photographed and documented.

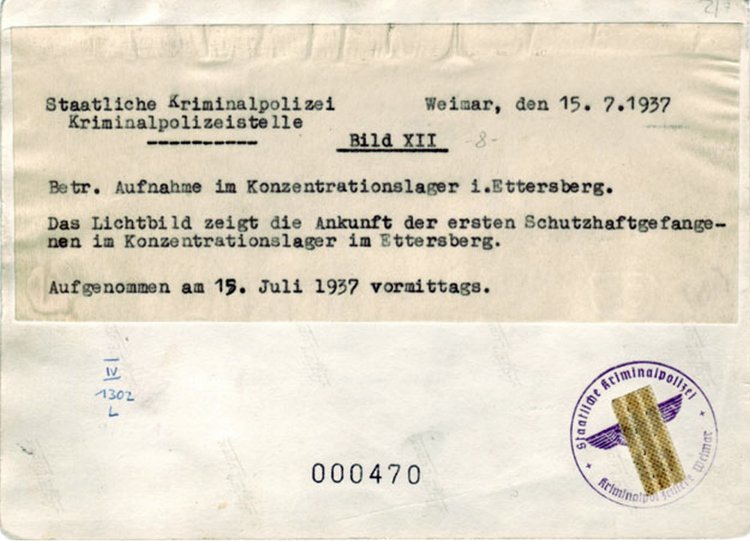

It was forbidden to take pictures in the concentration camp. The grounds had the status of a military facility, and prohibition signs were posted everywhere in plain view. Only the camp commander could authorize the taking of photographs in the camp. This task was soon assumed by the staff of the photo department (a subdivision of the records office) – initially members of the SS, later primarily inmates. Only the photos of the initial construction phase were taken by the Weimar criminal police, as the department had yet to be established.

The officers drew up a detailed documentation of the construction process, noting the individual work stages as well as the exact place and time each photo was taken. Numbering more than fifty, the photos were intended to provide evidence of the orderly performance of the work during the first four months. They show the clearing of the forest, road construction, and the erection of the first barracks and the camp gate. The inmate labourers ‘happen’ into the pictures more or less by chance. Three photos taken on 15 July 1937 show the first inmate transport on arrival in the Buchenwald concentration camp. The brutality of the armed guards is not visible in these scenes. The camp was supposed to make a well-organized, well-ordered impression.

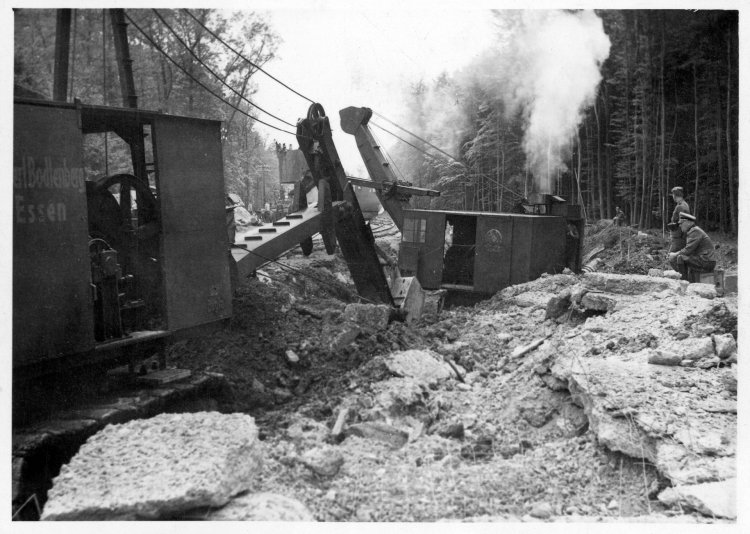

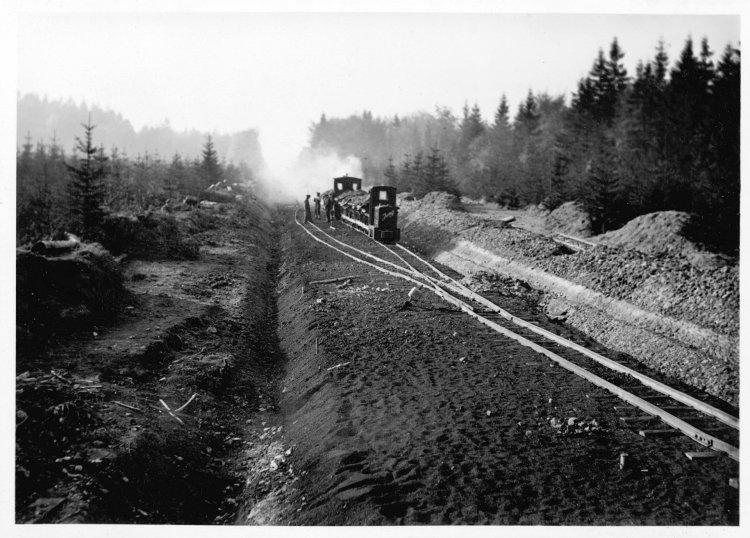

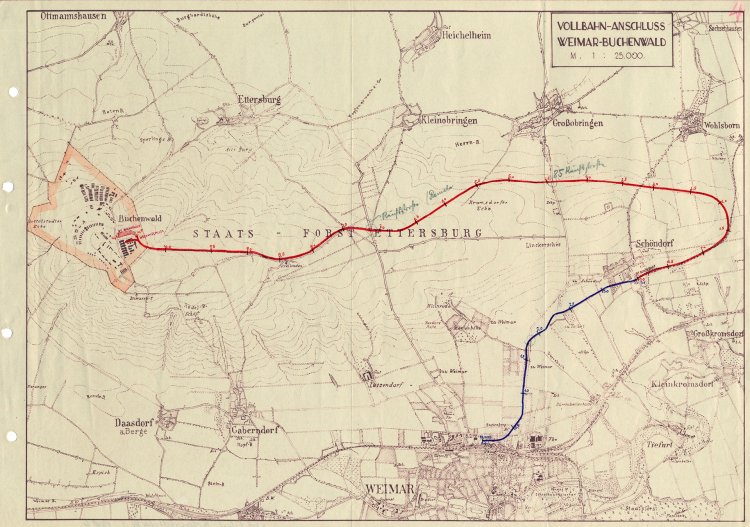

From April to June 1943, inmates performed similarly heavy labour in the construction of the rail connection from Weimar to Buchenwald. Throughout those three months, they were forced to work twelve-hour day and night shifts under the worst conceivable conditions. In the views taken by the photo department, however, the inmates look like normal, professionally equipped skilled workers. Nothing could be further from the truth: the railway line was officially opened on 21 June, but the inaugural train ride was the only one to take place for another six months, as the line was still far from completion.

Weimar criminal investigation department, 15 July 1937

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Weimar criminal investigation department, July 1937

Service Historique de la Défense, Vincennes

Weimar criminal investigation department, July 1937

Service Historique de la Défense, Vincennes

Weimar criminal investigation department, autumn of 1937

Service Historique de la Défense, Vincennes

Weimar criminal investigation department, 15 July 1937

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Weimar criminal investigation department, July 1937

Service Historique de la Défense, Vincennes

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, spring of 1938

Instytut Pamięci Narodowej

Weimar criminal investigation department, 20 August 1937

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Weimar criminal investigation department, 15 July 1937

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Weimar criminal investigation department, 15 July 1937

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Weimar criminal investigation department, 10 November 1937

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, autumn of 1938

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Theodor Hommes, SS Rottenführer, spring of 1938

Bundesarchiv – Militärarchiv, Freiburg

Central construction management of the Armed SS, spring of 1943

Landesarchiv Thüringen – Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar

Central construction management of the Armed SS, spring of 1943

Landesarchiv Thüringen – Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, spring of 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, spring of 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, spring of 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Central construction management of the Armed SS, spring of 1943

Landesarchiv Thüringen – Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar

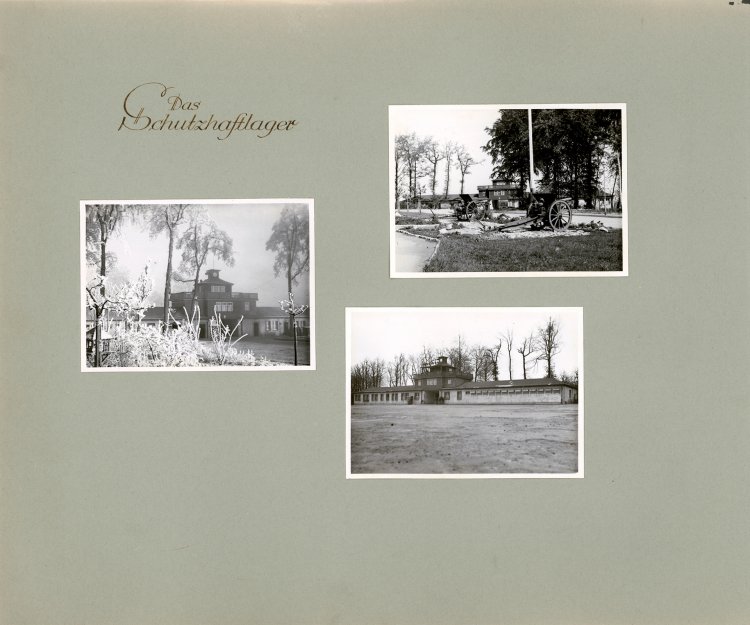

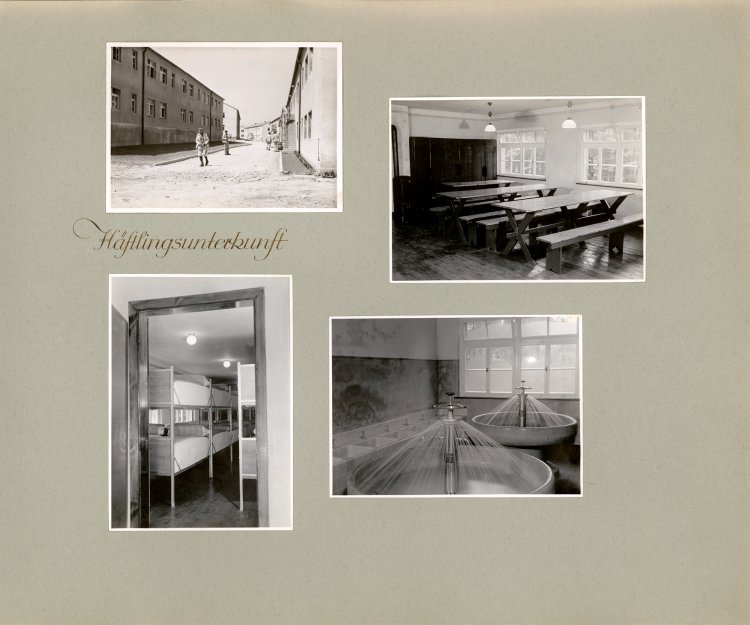

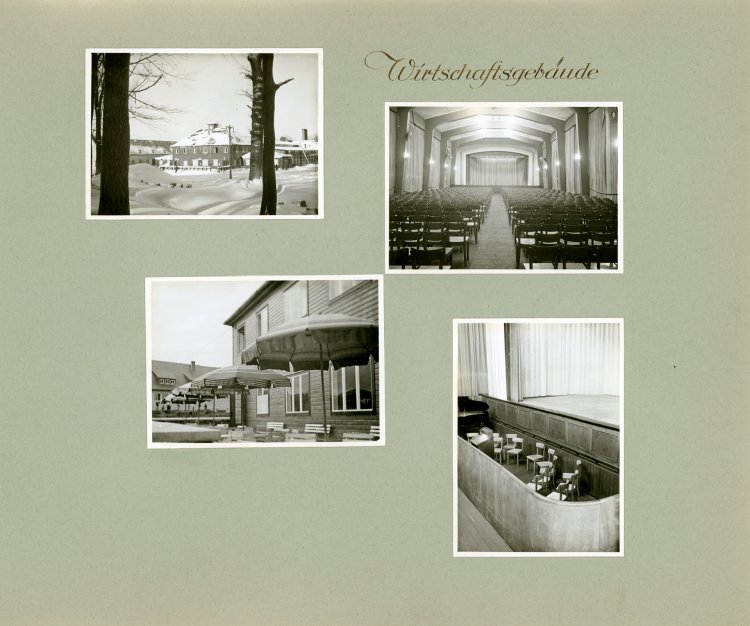

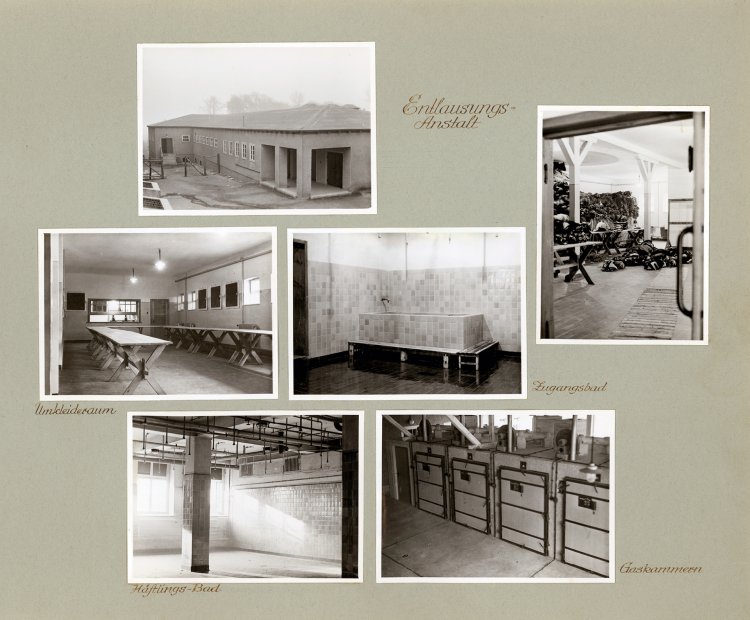

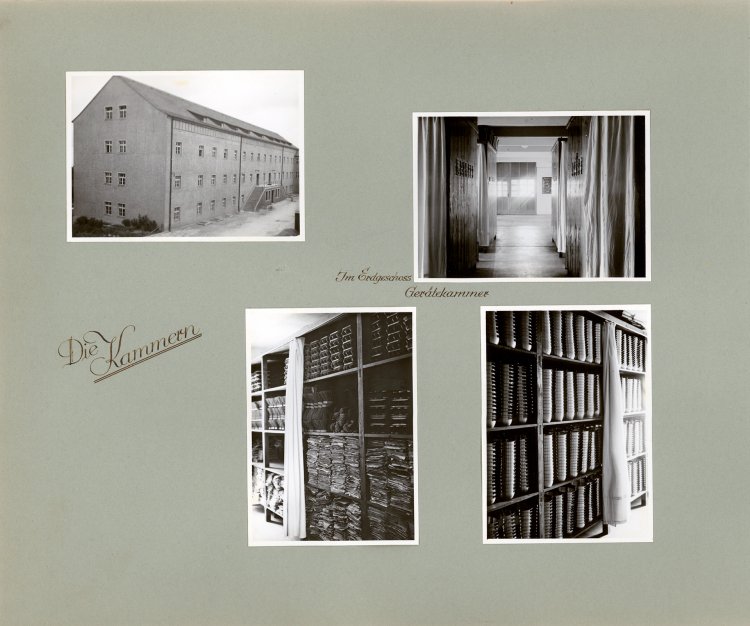

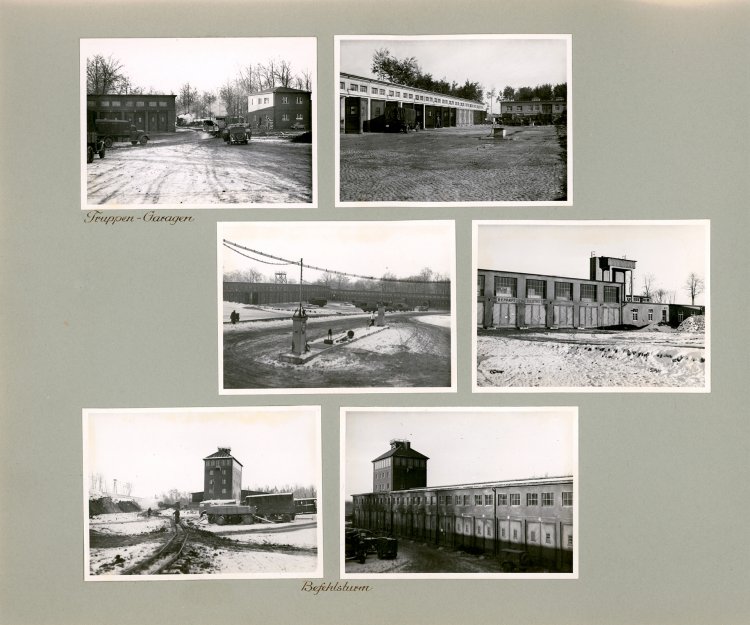

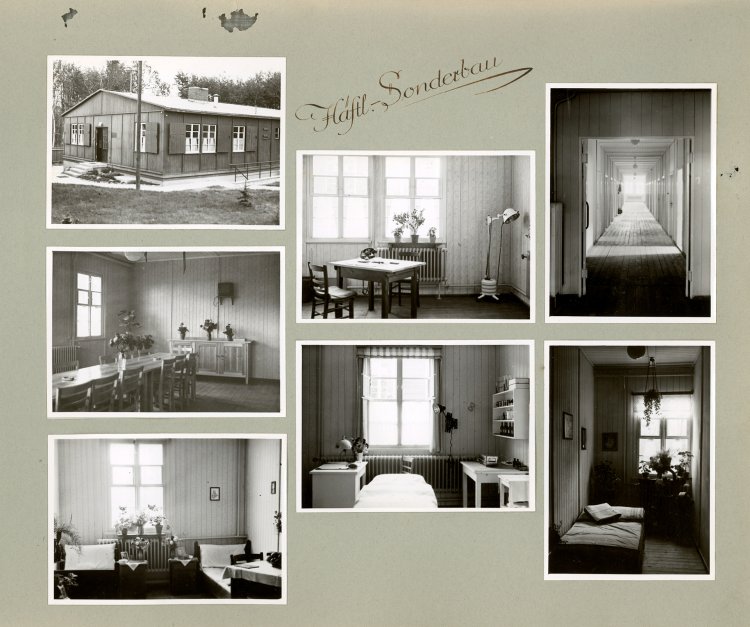

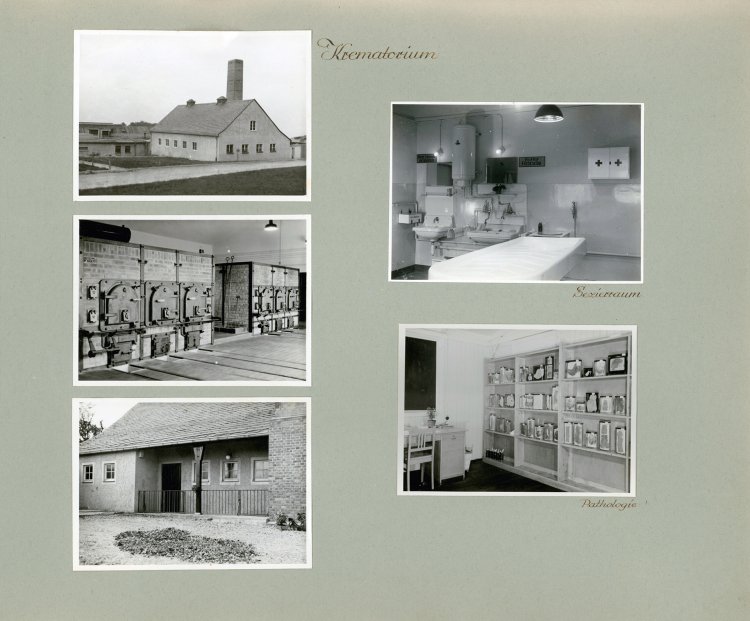

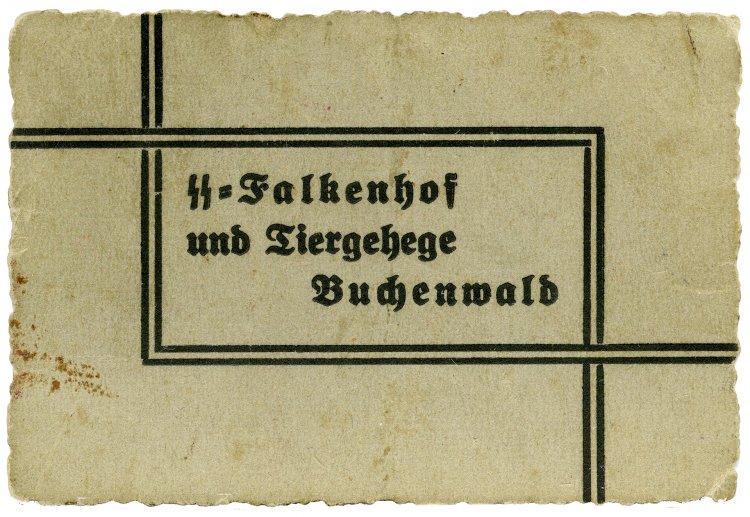

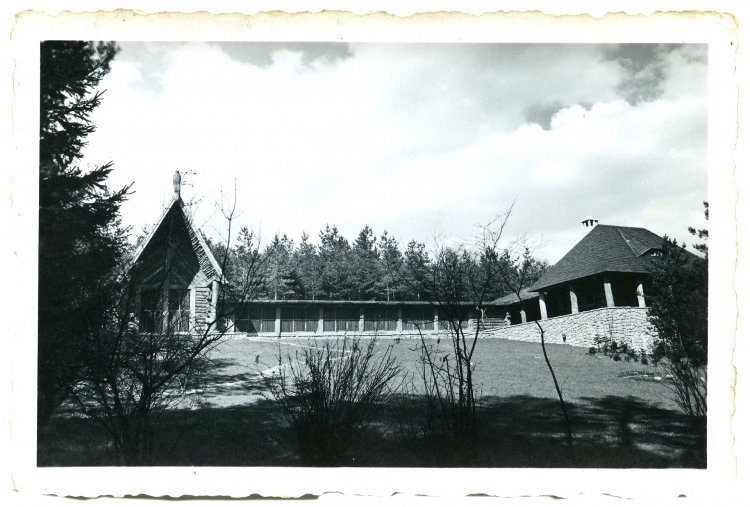

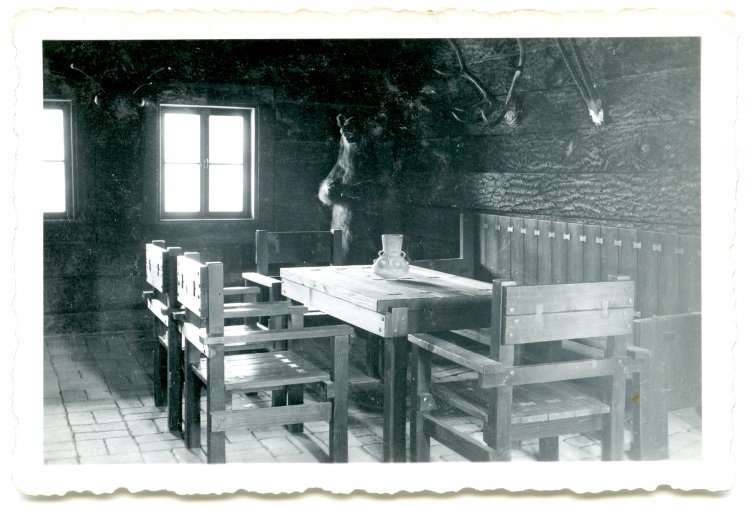

Buchenwald as a Model Camp

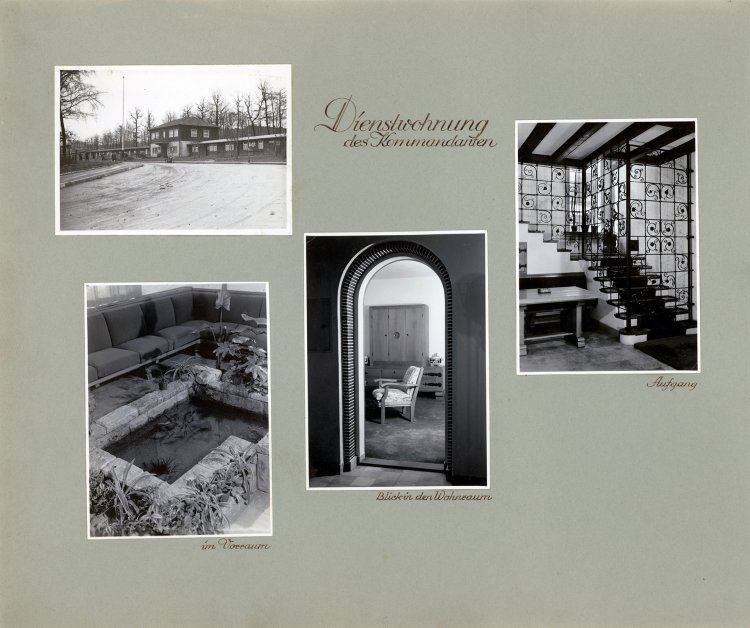

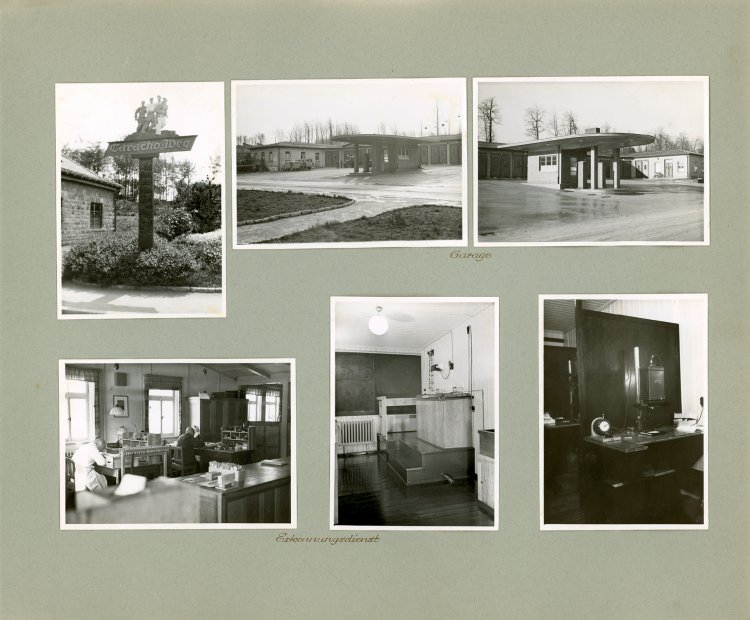

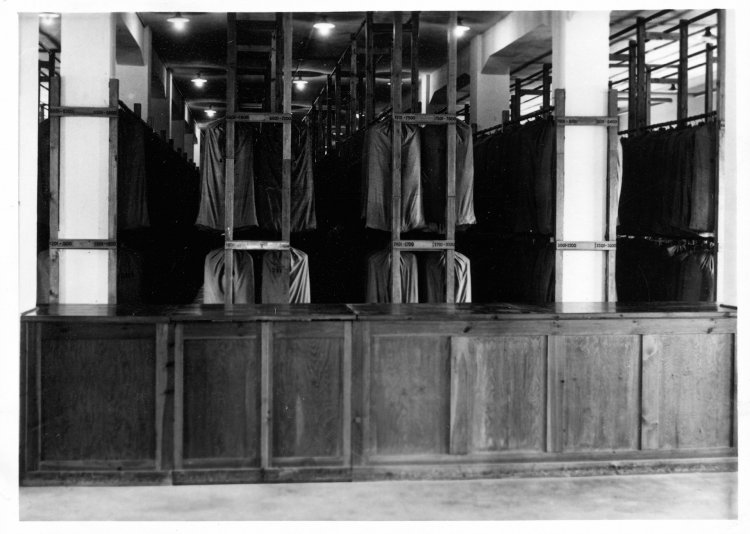

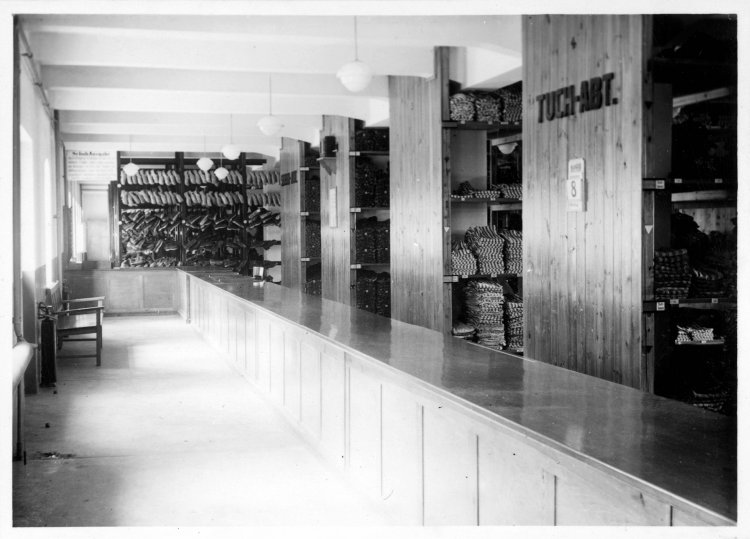

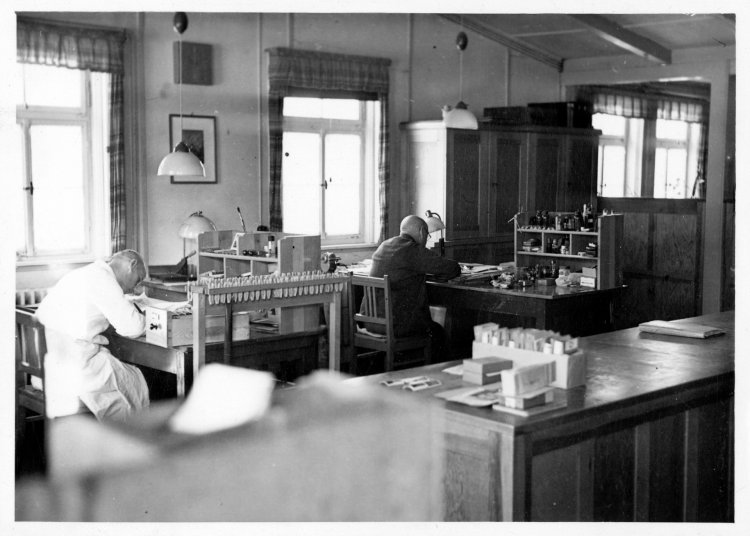

In 1943, Hermann Pister took command of the concentration camp. His superiors later praised him for having “turned Buchenwald into a model camp”. The photo album dates from late 1943.

The album illustrates the commander’s vision of a well-functioning model camp. It is conceivable that Pister planned to use it to demonstrate the success of his work to outsiders and his superiors.

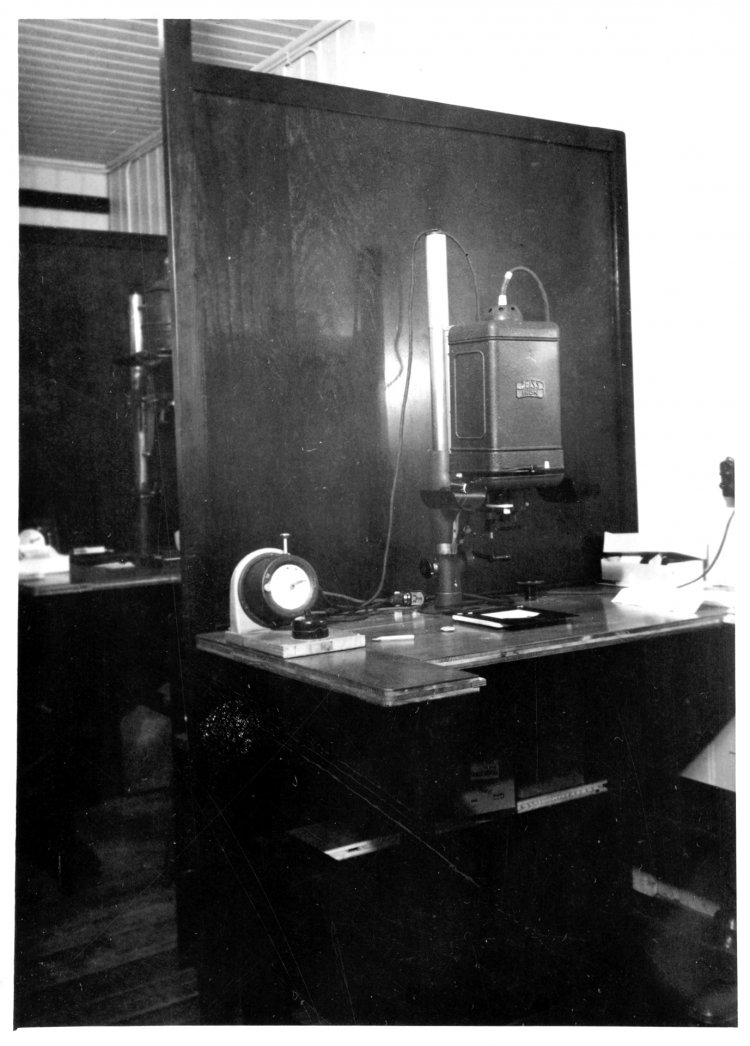

Two thirds of the album, which contains altogether 235 photos, are devoted not to the actual camp, but to the SS base. Here it is a picture-book of perfectionism and technical progress, showing the imposing reception and offices of the commander, the heating system, the armaments factory, and the troop garages. A remarkable feature is the excessively huge-looking command tower in the midst of the Armed SS troop garages. It was so high that it could be seen from Weimar.

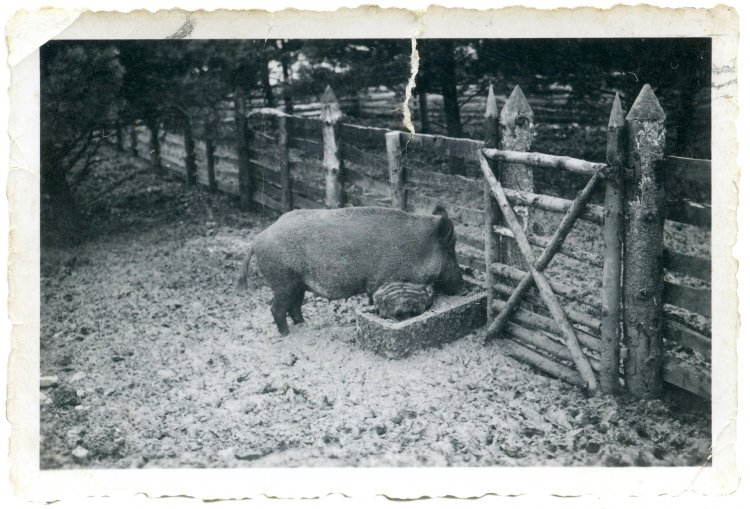

The inmates’ camp is devoid of people in the photos, and depicted as modern, orderly, and hygienic. Only the spanking clean crematorium with its display of preserved human specimens offers a hint of the camp’s true purpose. Large sections of the concentration camp are left out of account. The Little Camp in existence since 1943 – and acutely overcrowded due to the ongoing arrivals of mass transports – does not appear in a single photo. The inmates of that quarantine and transit camp were left to vegetate in windowless stables and, in the winter of 1944/45, in tents as well. The lives and deaths of the inmates play no role whatsoever in the album entitled “Buchenwald, Year-End 1943”.

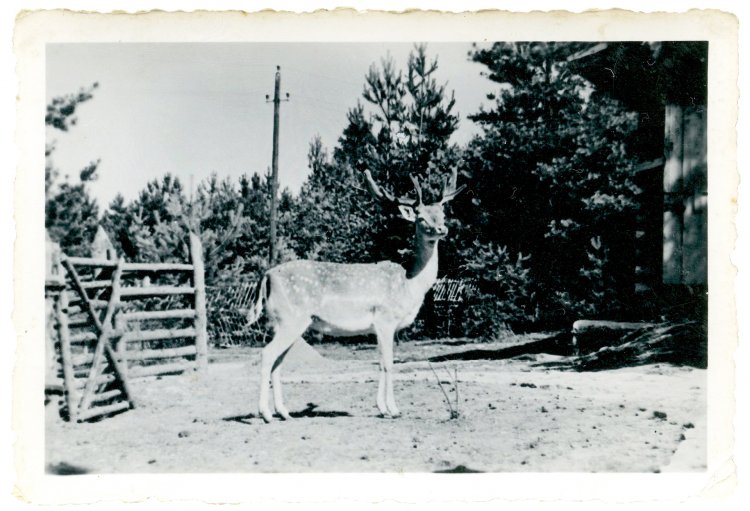

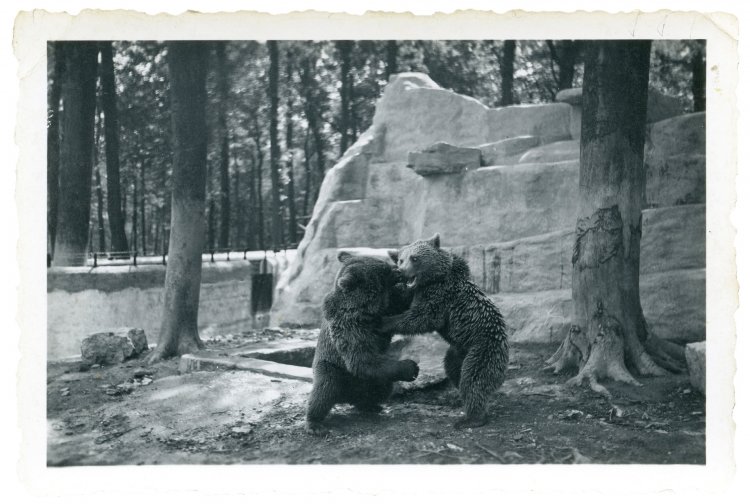

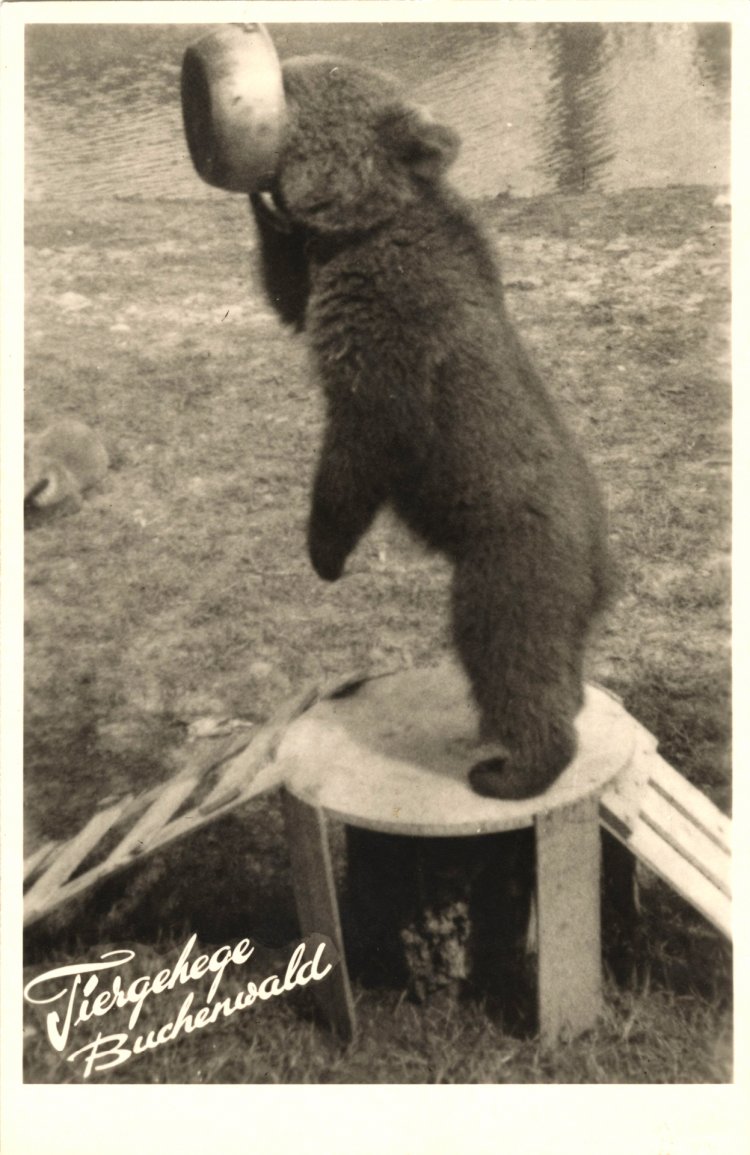

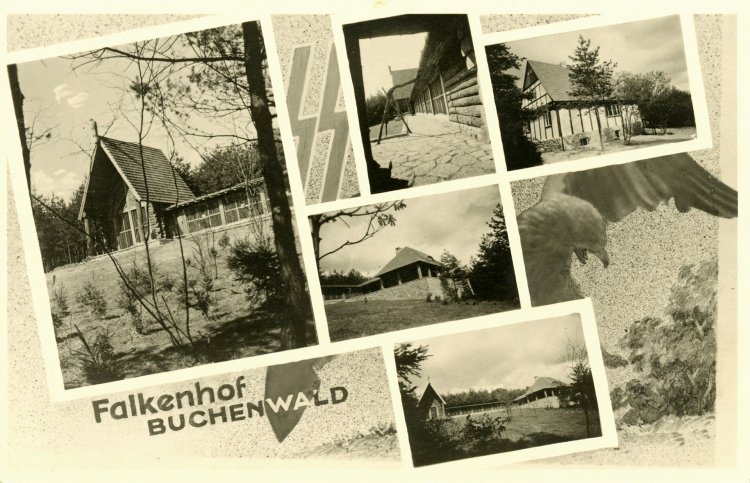

The photos were taken by photo department inmates on behalf of the SS; the layout was the work of the bookbinders’ detachment. The postcards and souvenir views of the Buchenwald Zoo, sent by visitors and soldiers, have a downright absurd quality: cute bears romp about beneath the trees.

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, late 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, late 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, late 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 8 November 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, late 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, late 1943

Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Besançon

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1939

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1939

Buchenwald Memorial Collection

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, 1939

Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

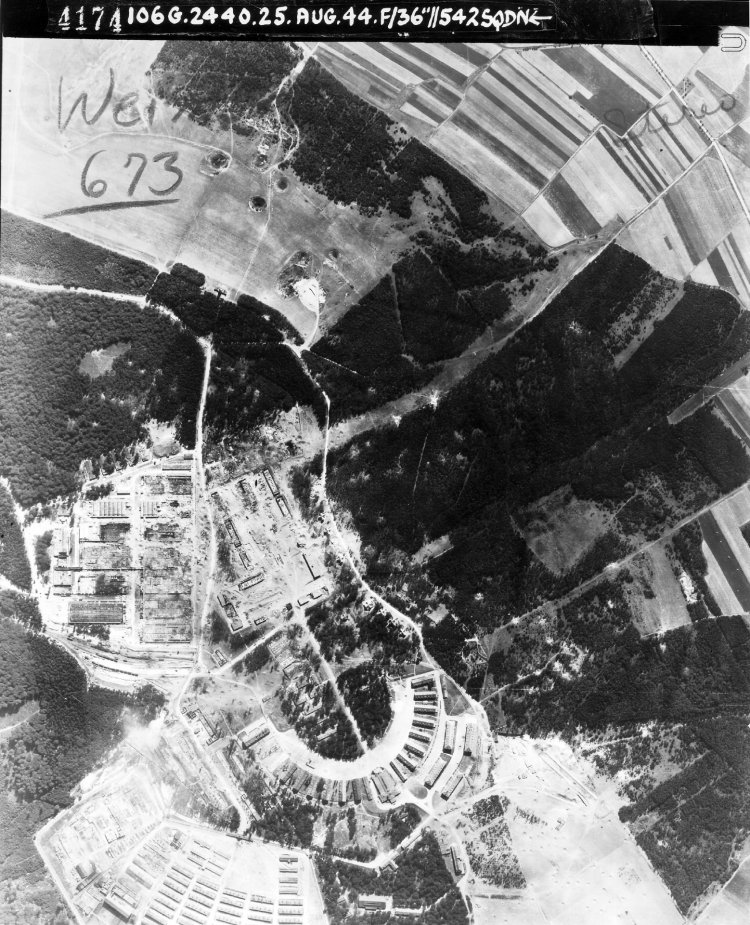

The Aerial Attack of 1944 – The Beginning of the End

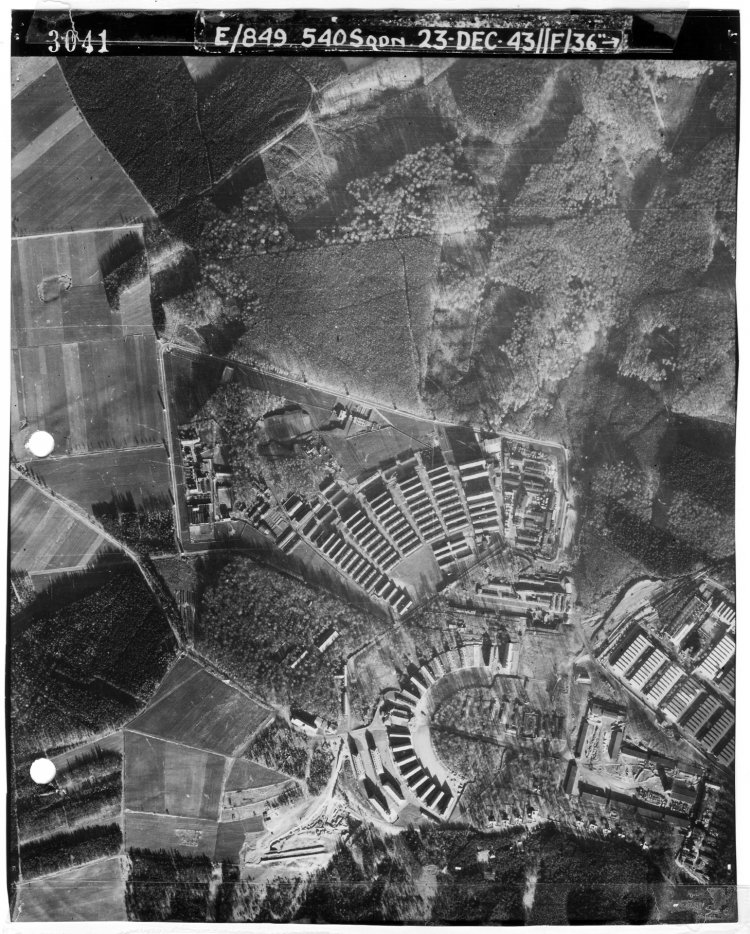

At noon on 24 August 1944, the 1st Bomber Division of the 8th US Air Fleet attacked the armaments works adjacent to the camp. Thanks to precision bombing, large proportions of the Gustloff Works II and the SS facilities were destroyed, while hardly any damage was done to the inmates’ camp. The attack ushered in the final phase in the history of the Buchenwald concentration camp. The Allied aerial views taken before and after the raid show the camp at the height of its structural development.

Beginning in the spring of 1943, as many as 3,500 inmates were forced to work in the Wilhelm Gustloff Works II manufacturing rifles and, later, the control gear for the “V2” rocket. The Allied aerial mission was to destroy this weapons factory. In order to map the production halls beforehand, Allied reconnaissance planes flew over the camp a number of times; in the summer of 1944, with 31,000 inmates, it was at the limits of its capacity. For the first time, the American military command obtained a clear picture of the Buchenwald SS garrison and concentration camp without the SS being able to prevent it. Whereas on 24 August clouds of smoke made a direct view of the camp from the air impossible, the enormous damage wrought to the facilities could already be discerned in the course of the following day. The photos aided American aerial reconnaissance in arriving at a precise evaluation of the damage and increasing air-raid efficiency.

During the air attack on 24 August 1944, the SS prevented the inmates at work in armaments production from leaving the factory grounds. As a result, 2,000 of them were injured and 388 died. The power and water supply systems collapsed; even roll call failed to take place for several days. Badly shaken, the SS command was compelled to reorganize its operations. On behalf of the SS, inmates from the photo department documented the destroyed factories and buildings a few days after the air raid. The photos were presumably used to illustrate the damage report drawn up for the authorities in Berlin. They show the immense degree of destruction and the clearing of rubble with inmate labour.

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 3 September 1944

National Archives at the College Park, Maryland

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, after 24 August 1944

F.N.D.I.R.P., Paris

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, after 24 August 1944

F.N.D.I.R.P., Paris

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, after 24 August 1944

F.N.D.I.R.P., Paris

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, after 24 August 1944

F.N.D.I.R.P., Paris

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, after 24 August 1944

F.N.D.I.R.P., Paris

Buchenwald concentration camp records office, after 24 August 1944

F.N.D.I.R.P., Paris

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 31 March 1944

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 23 December 1943

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 24 August 1944

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 25 August 1944

National Archives at College Park, Maryland